The once and future street

The Strøget in Copenhagen is the world’s longest pedestrian shopping street. (Photo by Dr. Al-Barjas)

(First of two parts)

I had the privilege of taking renowned architect and new urbanism pioneer Peter Calthorpe around Metro Manila during his first visit to the Philippines in the early ’90s.

One of the questions he asked then was, “where is the most beautiful street in Metro Manila?” I was surprised by the question, but was even more surprised that I couldn’t readily answer his innocent query. I wished then that I could take him to Roxas Boulevard with its famous sunset, but realized it was not the street per se that was remarkable. Besides, the reclamation of the Bay, which was well underway then, had diminished the waterfront grandeur of Burnham’s vision for the boulevard.

We instead took him to McKinley Road which, in the ’90s, had wider sidewalks, a full canopy of trees arching over a two-lane carriageway and a drive that offered a scenic view of Manila Golf (only a chain link fence separated the golf course from the road back then).

Picturesque as it was during that time, I retrospectively realized that McKinley Road was quite sterile with the high walls and imposing gates of the grand homes along it. It was impressive to drive through during the day, but unnerving to walk in at night.

Article continues after this advertisementIt nevertheless functioned the way it was designed—as an elegant arrival to the ultra-exclusive villages that flank it—private, luxurious, distinctive. It was beautiful in its own rarefied way.

Article continues after this advertisementDesigning ‘the beautiful street’

More than 30 years later, the answer to Peter Calthorpe’s question still eludes me. I’m sure attractive streets abound in various places all over the country and there are a few noteworthy streets in many new developments.

Over the years as a land planner, I sought to design “the beautiful street”. Ultimately, however, the effort was largely technical and visual with most designs ending up within gated and homogenous enclaves, hidden from public view and shielded from collective enjoyment.

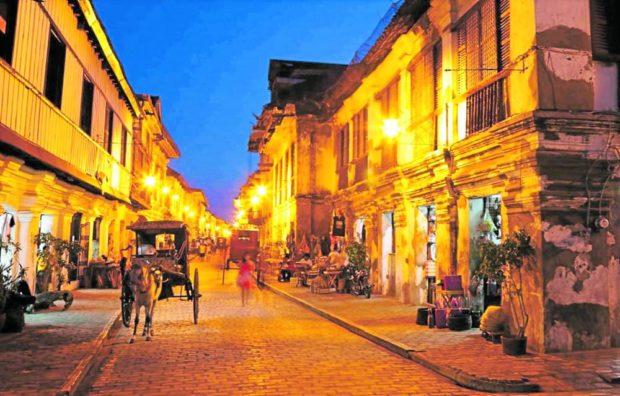

The struggle is in defining what makes a street beautiful; and beautiful for whom? We are in awe of the grand boulevards of Paris, enchanted by the streets of Cotswold in England, fascinated by the hilly streets of San Francisco, or charmed by the streets of old town Vigan.

The common thread among these attractive streets is that they are part of the public fabric of the city. A street, therefore, is beautiful because of (or, some may argue, despite) its public nature. Cities have long expressed the public-private dilemma and no other urban element best captures this perplexity than in the street itself.

A shared good

The street is the most contested element in the built environment. It is a communal space, yet it is also an implicit extension of the private realm, often appropriated by property owners immediately fronting them. Embedded in the form and function of the street is the constant struggle between public and private, challenging our conceptions of what is personal and what is shared.

Streets are concurrently, no one’s, each one’s and everyone’s.

Pre-modern cultures saw the street as largely a shared good, with a porous boundary between the domestic and communal, using courtyards as transitional elements that set the hierarchy of “privateness”.

The nature of the street space itself is defined depending on who is using it at that point in time, whether it is a place to sell merchandise, a path to traverse, a venue to chat with neighbors or a space for children to play. Its multifunctionality within its limited dimensions lends to constant negotiation for control among its varied users. One only needs to recall the streets of Divisoria to imagine the chaotic ballet that happens within traditional downtown streets.

The pervasiveness of individualistic and liberal values during modern times shifted our concept of the public realm. The individual began to take precedence over the collective and was reflected in all aspects of life and the built environment.

Personal freedom, independence, privacy and the self-interested virtues of capitalism became the ideals of society. Individualism, as the philosopher Alexis de Tocqueville once stated, “sapped the virtues of public life”.

The street and the city adapted to this individualistic ideal. Neighborhoods gave way to gated private enclaves segregated by income. Mass mobility gave way to private mobility and the private car became the sought-after symbol of prosperity. Streets lost their communal purpose and are now designed to serve private vehicles nearly exclusively.

The rich complexity of the polyfunctional street as “place” was lost to its “movement” function when it became the exclusive domain of the car. Beauty as an ideal for the street was lost to the need to convey ever more vehicles faster and farther. Formerly the seams of neighborhoods, streets became the edges of gated communities.

With the automobile as a status symbol, the wide village street became the indicator of prestigious address. One only needs to see the street standards of our building and subdivision codes or to observe the highways and skyways that bisect the sprawling metropolis to observe how much we have prioritized vehicular mobility over all other functions of the street.

The future of the street

So, is the quest for the beautiful urban street a lost cause? Hopefully, not.

The pandemic raised public awareness on the value of the street as a multifunctional space for various mobility modes and place activities. Ironically, there was an apparent resurgence in collectivism during the time of pandemic isolation.

On one hand, there is a growing movement towards car-free streets, car-free districts, and shared streets. On the other, technology-driven innovations for private mobility such as electric vehicles, self-driving cars are also joining the mainstream. Any of these trends could define the future of the street but the end state will likely be a hybrid of these possibilities.

The struggle between public and private, collective, and individual, will likely persist in the streets of the future.

(To be continued)

The author is founder and principal of JLPD, a master planning and design consultancy practice. www.jlpdstudio.com