G7 fails to reach intervention deal to ease pain of soaring dollar

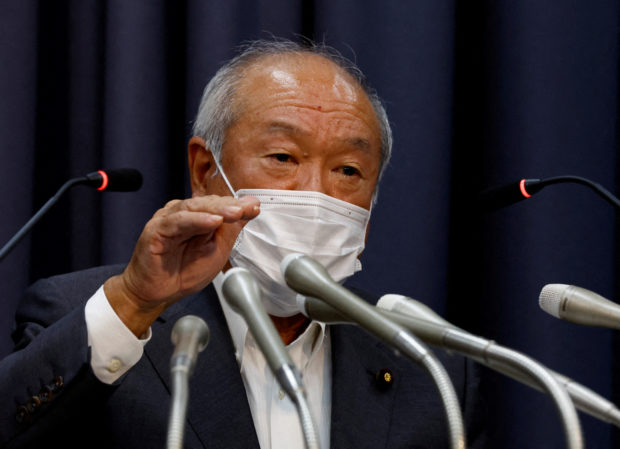

Japan’s Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki speaks at a news conference after Japan intervened in the currency market for the first time since 1998 to shore up the battered yen in Tokyo, Japan September 22, 2022. REUTERS/Kim Kyung-Hoon/File photo

WASHINGTON – Japan and other countries facing the fallout from a soaring U.S. dollar found little comfort from last week’s meetings of global finance officials, with no sign that joint intervention along the lines of the 1985 “Plaza Accord” was on the horizon.

With a strong push from Japan, finance leaders of the Group of Seven advanced economies included a phrase in a statement on Wednesday saying they will closely monitor “recent volatility” in markets.

But the warning, as well as Japanese Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki’s threat of another yen-buying intervention, failed to prevent the currency from sliding to fresh 32-year lows against the dollar as the week came to a close.

While Suzuki may have found allies grumbling over the fallout from the U.S. central bank’s aggressive interest rate hike path, he conceded that no plan for a coordinated intervention was in the works.

“Many countries saw the need for vigilance to the spill-over effect of global monetary tightening, and mentioned currency moves in that context. But there wasn’t any discussion on what coordinated steps could be taken,” Suzuki said in a news conference on Thursday after attending separate meetings of the G7 and G20 finance leaders in Washington.

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen made clear that Washington had no appetite for concerted action, saying the dollar’s overall strength was a “natural result of different paces of monetary tightening in the United States and other countries.”

“I’ve said on many occasions that I think a market-determined value for the dollar is in America’s interest. And I continue to feel that way,” she said on Tuesday, when asked if she would consider a Plaza Accord 2.0 agreement.

No yen support

In 1985, a destabilizing surge in the dollar prompted five countries – France, Japan, the United Kingdom, the United States and what was then West Germany – to band together to weaken the U.S. currency and help reduce the U.S. trade deficit. Following the deal, named the Plaza Accord for the famed New York hotel where it was hammered out, the dollar shed roughly 25 percent of its value over the ensuing 12 months.

With no current U.S. interest in engineering that kind of deal, other countries have to find ways to mitigate the pain stemming from a strong dollar, which has forced some emerging economies to hike interest rates to defend their currencies even at the cost of cooling economic growth more than they want.

Emerging Asian nations have seen significant capital outflows this year that are comparable to previous stress episodes, heightening the need for policymakers to build liquidity buffers and take other steps to prepare for turbulence, said Sanjaya Panth, deputy director for the International Monetary Fund’s Asia and Pacific Department.

“The situation for Asian economies is very different from where they were 20 years ago” as countries accumulated foreign reserves that make them more resilient to external shocks, Panth told Reuters on Thursday on the sidelines of the IMF and World Bank annual meetings in Washington.

“At the same time, the rising debt levels, particularly in some economies in the regions, are a concern,” he said. “Some form of market stress cannot be ruled out.”

The Bank of Korea delivered its second-ever 50-basis-point interest rate hike on Wednesday and made clear the won’s 6.5 percent slide against the dollar in September that drove up import costs played a key role in the decision.

South Korea’s central bank Governor Rhee Chang-yong said on Saturday he does not sense an interest among U.S. officials to stem the dollar’s strength through joint intervention.

But he said some kind of international cooperation on the dollar may be needed “after a certain period.”

“I think a too-strong dollar, especially for a substantial period, won’t be good for the Unites States either, and actually I’m thinking about the long-term implication for the trade deficit, and maybe another global imbalance may happen,” he said.

In Japan, the onus is on the government to deal with a renewed plunge in the yen, caused in part by the policy divergence between the Federal Reserve’s determination to raise U.S. interest rates and the Bank of Japan’s resolve to keep borrowing costs ultra-low.

At the news conference where Suzuki issued his warning about sharp yen falls, BOJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda ruled out anew the chance of a rate hike.

The dollar jumped about 1 percent to a fresh 32-year high of 148.86 yen on Friday, testing authorities’ resolve to combat the Japanese currency’s relentless slide. The dollar/yen is now up roughly 2 percent from levels when Japan intervened on Sept. 22 to buy yen for the first time since 1998.

Japanese policymakers have said they won’t seek to defend a certain yen level, and instead will focus on smoothing volatility.

Masato Kanda, the country’s top currency diplomat, told reporters on Friday that authorities were ready to take “decisive action any time” if excessively volatile yen moves continued.

Even moderating abrupt yen moves, however, could be a challenge as Kuroda’s assurance that the BOJ will keep interest rates in negative territory gives investors a green light to continue dumping the currency.

“It’s impossible to reverse the yen’s downtrend with solo intervention,” said Daisaku Ueno, chief forex strategist at Mitsubishi UFJ Morgan Stanley Securities.

“Once the yen falls below 150 to the dollar, it’s hard to predict where its depreciation could stop because there’s no technical chart support until around 160,” he said.