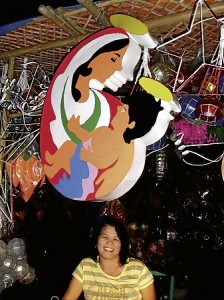

Profile of some lantern makers in ‘Sampernandu’

ONE businessman sold more than 10,000 lanterns just two weeks before Christmas, higher by 2,000 pieces from his 2010 sales.

CITY OF SAN FERNANDO—Thanks to the Christmas tradition, a high sense of optimism after two severe typhoons and a feeling of hope, lanterns made in this Pampanga capital are enjoying brisk sales.

Ernesto Quiwa had sold more than 10,000 lanterns two weeks before Christmas day, higher by 2,000 pieces from his 2010 sales.

A grandson of Francisco Estanislao, the acknowledged pioneer in the craft of making giant lanterns, Quiwa has seen the ups and downs of the business that he has been engaged in since 1964.

“Mas masali la ngeni (The lanterns are more saleable now),” Quiwa, 64, says. “Mikapag-asa la siguru reng tau kang P-Noy ya siguro mas manyali la (The people may have found hope in President Aquino that’s why they’re spending more).”

The peace dove that was one of the symbols used by Mr. Aquino in his 2010 campaign has become a part of the standard design in this city’s street lanterns for the second year.

It helped, too, that the city government was promoting the lanterns through the Department of Trade and Industry’s One-Town, One Product campaign, says Quiwa.

San Fernando taps Philippine embassies abroad to reach Filipino communities, city administrator Ferdinand Caylao says.

Roland Quiambao, on the other hand, had produced 3,000 decorative lanterns for local governments, fiestas, beauty pageants and shopping malls as of November. These lanterns were larger in sizes than the 3,000 household lanterns he made in 2010.

Better sales

“As long as there is Christmas, lanterns will be part of the celebrations. I think sales are also better this year because Filipinos want to be more happy in the aftermath of [Typhoons] Pedring and Quiel,” says Quiambao, 56. He has been in the business since 1980.

Daisy Flores, 46, considers 2011 a busy year for her. From just 700 lanterns last year, her backyard churned out 630 star-shaped lanterns and 16,000 round-shaped lanterns of three sizes up to November.

These, she says, excluded the few subcontracts she accepted in the first half of the year for her neighbors in Sitio Macabacle in Barangay Dolores here.

She has felt the economic slump, though. “We used to go sleepless in Macabacle when sub-contracts come. In the past months, there’s much idle time in between,” she says.

While Quiwa prefers using colored plastic, fiberglass or hand-made paper as sheets for the traditional lanterns, Quiambao and Flores say they are forced at times to produce lanterns made of capiz because their market niches demand these.

Beginnings

Quiwa was working as driver at the defunct bus line La Mallorca in 1964 when businessman Odon Gopiao helped him sell his 200 lanterns in gasoline stations and eateries in Manila.

The next year, Gopiao asked Quiwa to double his production. Every piece sold like hot cake that other lantern makers followed suit.

“Mikyapus la reng Dolores (The lantern makers in Dolores copied what we did). The business boomed,” says Quiwa, who maintains a stable of 200 workers.

ROPE lights made in China and fashioned by Filipinos into various shapes and sizes have penetrated the traditional parol market.

His success saw him doing exhibits abroad.

Quiwa teaches the craft and his recent students were inmates in a Laoag City prison.

In June, he and his team stayed in Ilocos Norte to make 200 pieces of Christmas decors for local governments. His lanterns sell for P700 to P2,800.

He is not threatened by China-made lanterns or rope lights.

“Why should I? Items made in China last for only a year or less. Lanterns we make in San Fernando last for five years or more. And they’re safe to use and of good quality,” Quiwa says.

‘Word of honor’

The secret of Flores’ staying power in the male-dominated business is her “word of honor.”

“Owners of hardware stores in Metro Manila give me materials without asking for collateral. They trust me because I pay on the agreed time,” Flores says. This, she points out, was how her P10,000 capital in 1993 grew.

Like Quiambao, she is concerned about the future of the traditional lanterns. Around here, old folks call these “Sampernandu,” a local take of San Fernando, the patron of the city.

“More jobs are made when we make the traditional lanterns. Even children can cut or glue the patterns so they earn money for school,” she says.

On a regular basis, she has a team of 10 people, mostly relatives, for the production.

Quiambao used a P5,000 loan from the Department of Social Welfare and Development in 1980 to begin his business.

From having two helpers, he now has 40 workers to meet contracts.

Quiwa, Quiambao and Flores are among the 12 registered lantern makers in the city. Nine others hold temporary permits, data from the city government showed.

About 100 others have not registered their lantern-making business because they consider their establishments to be small, seasonal or they prefer to remain underground to skirt taxes.

A number of them serve as sub-contracting or marketing arms of registered firms, it was learned. The standard mark-up in the industry is 30 percent to cover operational costs.

Eric Quiwa, among the newest in the business, has found the competition to be tough but has learned that those who are creative get an edge.

In 2010, he sold 80 lanterns. Up to the first week of December, he had sold 200 pieces already. His firm, Fiberlan, specializes in fiberglass lanterns.

“I think the biggest promoter of lanterns is our city government and the private sector because the giant lantern festival that they stage always showcases the best of our artistry,” says Quiwa.