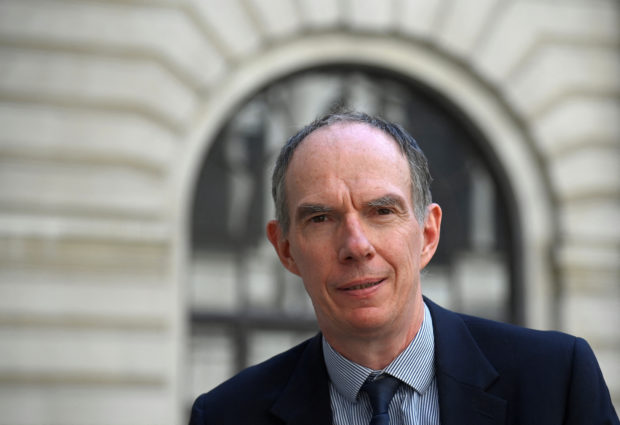

Bank of England Deputy Governor Dave Ramsden sits for a portrait during an interview with Reuters, at the Bank of England, London, Britain, August 8, 2022. REUTERS/Toby Melville

LONDON – The Bank of England will probably have to raise interest rates further from their current 14 year-high to tackle inflation pressures that are gaining a foothold in Britain’s economy, BoE Deputy Governor Dave Ramsden said.

Inflation’s spread was now showing up in rising British pay and companies’ pricing plans, having originally been triggered by the reopening of the world economy from COVID-19 lockdowns and then by Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Ramsden told Reuters.

Inflation is expected to return to the BoE’s 2 percent target – down from above 9 percent now and a projected peak of 13 percent in October – as the economy goes into a recession and borrowing costs rise.

But there was also a risk of an inflation mentality developing, Ramsden said.

“For me personally, I do think it’s more likely than not that we will have to raise Bank Rate further. But I haven’t reached a firm decision on that,” Ramsden said in an interview.

“I’m going to look at the indicators, look at the evidence as we approach each upcoming meeting.”

The BoE last week raised borrowing costs by the most since 1995 as it took Bank Rate to 1.75 percent from 1.25 percent, its sixth increase since December, compounding the biggest two-year disposable income hit for households since at least the 1960s.

“We know that what we’re doing is adding to an already very challenging environment,” Ramsden said. “But our assessment is we needed to act forcefully to ensure that inflation doesn’t become embedded.”

Ramsden, a former senior official at Britain’s finance ministry who joined the BoE in 2017, said a fall in inflation expectations in financial markets was encouraging, as were signs that households and companies thought central bankers would get to grips with the problem.

Asked if Bank Rate was close to hitting a peak, Ramsden said that over the past year the BoE had to deal with the end of COVID-19 restrictions that hammered Britain’s economy and the Russia-Ukraine war that pushed inflation to its 40 year-high.

“We’re in extraordinary period where a lot is changing. So I wouldn’t want to make any predictions about where Bank Rate is going to end up,” Ramsden said.

“I guess one thing I would say is I think inflation expectations remain anchored and that’s really important.”

Bond sales

As well as raising interest rates, the BoE plans to move Britain’s economy off its massive stimulus programs by starting to sell government bonds – a process known as quantitative tightening (QT) – as soon as next month.

Asked whether the BoE would continue to sell bonds if it needed to go in the opposite direction and cut interest rates to support the economy – something investors expect to happen next year – Ramsden said that was a possible scenario.

“I’m certainly not ruling out a situation where when we look at the risk to the economy, having been raising Bank Rate, at some point we then have to start lowering it quite quickly,” he said. “I can imagine situations, yes, where we’ll carry on… with a pace of QT in the background.”

The tightening effect of selling down the BoE’s bond stockpile was likely “at the margin,” said Ramsden who as the BoE’s deputy governor for markets is in charge of its balance sheet.

Ramsden also pushed back at criticism of the BoE’s inflation-fighting record by Liz Truss, the front-runner to become Britain’s next prime minister, and her supporters some of whom have suggested the BoE should have less independence.

Ramsden said British inflation had averaged 2 percent – the BoE’s target – over the 25 years after the central bank was granted operational independence in 1997.

While there was a case for learning from the experience of other central banks around the world – something Truss has proposed – there would be risks in any attempt to give politicians more of a say over how to set interest rates.

“I think it’s perfectly reasonable to look at international experience … and see how its how it’s operating,” Ramsden said. “That’s quite distinct … from going back and revisiting independence itself.”