Improving lolo’s recipe for La Paz batchoy noodles

CITY OF CALAPAN – He was jobless, when along with his wife, he migrated to Calapan City from Iloilo in 1990.

Duane Delicana, however, was fearless and undaunted by the challenges that routinely faced newcomers like him to the city.

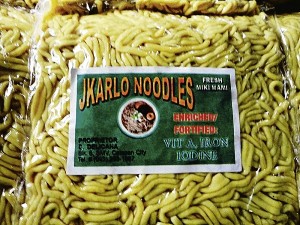

Apparently, the toil of the early years already paid off for today he is owner and manager of the JKarlo noodles factory.

Located in Sta. Maria Village in this city, the enterprise got its name from his children Jay K and Karl Austin.

A graduate of medical technology and a former salesman, Delicana started producing “miki mami” noodles in 1997, a pursuit fueled in part by the training he received from his grandfather whose fresh noodles were the main ingredient of the Ilonggo specialty “La Paz Batchoy.”

Article continues after this advertisementWhen Delicana and wife Marilyn, a pediatrician, arrived in Calapan City, they did not know of any acquaintance or relative in the place.

Article continues after this advertisementNot the type of husband who would depend on his wife for livelihood, he immediately plunged to the nitty gritty of making a living.

The couple rented an apartment for P1,000 a month in Barangay Calero in the city.

Even as Delicano knew by heart his lolo’s formula for noodles he wanted his noodles to be his own.

He spent many years trying to produce the right amount and mix of ingredients for his own noodles.

Fortunately, Marilyn and their helpers never gave up as “tasters” of the experimental noodles he concocted in the kitchen.

It came to a point when tasters were wishing there would be no plate of noodles to taste nor see, Delicana says in Filipino describing his “taste testing” years.

“Nakakaumay na,” he says of the taste tests.

“For a period of seven years each afternoon, we would taste the noodles because he wanted to get the accurate taste,” says his wife.

She reasons that if their own household members could not tolerate the noodles produced in their test kitchen how much more the customers.

Funds for a start-up were insufficient but Delicano insisted on doing everything right, especially with respect to cleanliness.

He ensures the workplace is spic and span and properly screened to ward off flies with stainless steel as the standard material for the kitchen tools.

He says that since competition was tough he and his wife focused on improving their product. His unofficial consultant was a friend who worked at the Food and Nutrition Research Institute (FNRI), an attached agency of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST).

In 2005, his tie up with the DOST began. He first invested on machines as his product relied on three kinds of machines for the processes of mixing the ingredients, producing the sheets of noodles and slicing them into thinner strands.

The next stages were cooking, blanching, cooling and putting the finished product inside sealed plastic bags.

It would take 45 minutes to cook one sack of flour that could produce 38-40 kilos of noodles, he says. Each pack weighed one kilo and was sold at P38.

Production per day was from 250 to 300 kilos, depending on the orders. Normally, the gross income per day was P9,000 to P10,000.

Set-up

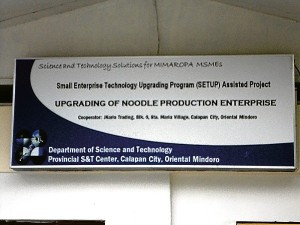

In 2007, the DOST, through its Small Enterprise Technology Upgrading Program (SET-UP) released a loan of P70,000 to Delicana so he could buy a cooking vat made of steel and other kitchen equipment.

In the years from 2005 and 2007, he underwent food safety seminars given by the DOST.

Delicana makes his own vacuum sealer, which extends the shelf life of the product, much to the delight of the DOST people. They even advised him to have the unique sealer patented because of the potential market for such an innovative gadget.

“We tell our customers that since we want to cater to those without refrigerators, the noodles will be good for four days even if it could last six to seven days,” he says.

A long-time client, Eden Villanueva says the noodles could last a month if refrigerates them.

Delicana is now scouting for the right kind of ingredients so he could come up with dried noodles that could last six months.

He is considering buying an oven drier so he could go into pancit canton production.

Delicana is currently scouting for alternatives to comply with the total plastic ban to be enforced in the city next year as mandated by city ordinances attuned to nationwide environmental regulations and campaigns.

His rules in the workplace? Honesty aside from cleanliness.

Delicana says he is not really a religious person but he ensures that his staff, three of whom are full-time workers, get their benefits from the Social Security System and Philhealth.

The workers get incentives for extra production aside from housing privileges.

One of his workers is Jimmy Tamunan. A son of a former worker in the enterprise, Tamunan has been working with the couple for the last 12 years.

Was it really difficult coming up with a winner of a product?

He says it is really all up to the entrepreneur as he held on to the belief that there is a solution to everything.

Delicana stresses the importance of concentrating on one thing and from there working hard to make improvements.

“Developing your business boils down to creating newness in your product,” he says.

photos by Madonna Virola, Inquirer Southern Luzon