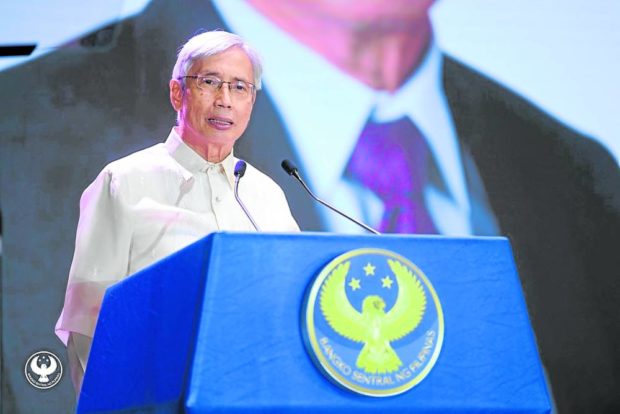

Inflation slayer rises to the challenge

The evening of July 13, a Wednesday, was supposed to be a restful one for Felipe Medalla who had been busy acclimatizing to his new job as the Governor of the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas.

Less than two weeks earlier, he was sworn into office by President Marcos as the country’s top banking and financial regulator with a mandate to slay inflation which, at 6.1 percent as of June, was its ugliest manifestation in four years.

As US financial markets opened that night, Philippine time, news flashed that prices of basic goods and services in the world’s largest economy had spiked by 9.1 percent—the highest in four decades.

Right there and then, Medalla knew something had to be done soon, and in such a way that would leave no doubt in the minds of Philippine financial market players that policymakers were themselves serious about combating inflation.

He “convened” the six members of the central bank’s Monetary Board (there remains one vacancy) through an instant messaging chat group (a skill his wife taught him) and made the case for a strong response from the central bank.

Article continues after this advertisementThis was, in itself, a challenge for several reasons. Just days before, outgoing BSP Governor Benjamin Diokno had reassured the media that the peso’s depreciation of over 10 percent since the start of the year was nothing to worry about.

Article continues after this advertisementMedalla himself echoed this a few days later, saying further interest rate hikes to stave off further currency depreciation and inflation would depend on more data showing them to be necessary.

Plus the central bank was right in the middle of a six-week cycle of monetary policy meetings during which interest rate adjustments are made. The next one was five weeks away.

“But I called everyone to a breakfast meeting on Thursday and told them that we had to act,” he recalls. He explained to colleagues that failure to implement a credible policy response would result in a deeper peso slide which would, in turn, push local inflation even higher.

The vote among the Monetary Board members was unanimous in favor of an “off-cycle” interest rate increase, and that afternoon, the central bank announced the largest increase in its overnight borrowing rate—which other banks use as basis for pricing their own loans—since the Estrada political crisis in 2000.

——————–

What that incident shows is that Medalla, despite being a “hardcore” economist since his youngest days out of De La Salle University (a 1970 cum laude graduate of economics and accounting), is not dogmatic about economic theory.

Having obtained a Master’s degree in economics in 1976 from the University of the Philippines, and an economics doctorate in 1983 from Northwestern University in Illinois, Medalla knows that economics works best when theory and practice are applied hand in hand.

To this end, he understands that while the primary goal is to keep prices of basic goods and services in check, doing so at all costs—even at the cost of economic growth—would result in nothing more than a Pyrrhic victory.

“We will tame inflation, yes. But we will do it while allowing the Philippine economy to stand on its feet, not by bringing it to its knees,” Medalla says.

He knows whence he speaks because this is not his first time to serve in government. He had previously been the country’s Socioeconomic Planning Secretary during the Estrada administration as the Director-General of the National Economic and Development Authority.

As part of the economic team back then, Medalla had to negotiate with foreign multilateral lenders to keep the lines of credit open for the Philippines, which was suffering an exodus of foreign investors due to the political crisis in 2000.

“After that experience, everything is easy,” he says.

It is a shame that the country will only have Medalla as central bank governor for a year, as he is serving only the unexpired term of his predecessor, and this is already his second stint on the Monetary Board (the law specifies a two-term limit).

But it doesn’t seem to bother him. Medalla says he has little need for more prestige or more money that high government office brings. He is happy with his wife, Pinky, living in their Quezon City home where all their four children grew up speaking Tagalog. He is content with loose-fitting business suits and comfortable shoes that will not land him on the cover of men’s fashion magazines, and he dislikes expensive watches or fancy vehicles.

“What’s the difference between a Toyota and a Benz if you’re both stuck in the same traffic jam?” he says.

For sure, Medalla will have more to offer to the Philippines after his term as central bank governor ends in a little over 11 months. But for now, he is laser-focused on the task at hand. And to this end, the 75-basis point off-cycle rate hike showed that he is willing to ditch economic dogma when faced with economic realities—always a welcome sign among financial market practitioners.

——————–

“Cometh the hour, cometh the man” it is often said.

On July 14, the hour came for aggressive central bank action, and along came Governor Medalla to help protect the value of money of Filipinos.

His role will be the same for the year ahead, albeit on a bigger scale: to slay inflation and, in doing so, return the institution that is the central bank to its true mission, its true self. INQ