Increasingly hawkish central bank assumes ‘firefighter’ stance

During such times, those who are closer to the frontline —bankers, traders, investors and the general public as well —look to authorities to address these problems to minimize their adverse effects.

Thus, newly installed Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP) Governor Felipe Medalla sees the financial regulator as a fire department that needs to fight the fire, and at the same time build its credibility; educate those who need to see that the fire is under control and the firefighters can be trusted to do their job.

Just as the Philippine economy’s bounce back from pandemic-induced recession was gaining momentum, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine on February has jacked up crude oil prices beyond the $100-barrel-mark and sent prices of other commodities rocketing.

With a contagion of rising prices rippling across the globe, inflation in the Philippines shot up past the upper end of the government’s target range of 2 to 4 percent.

Nationwide inflation was pegged at 6.1 percent in June and is expected to heat up further for the remainder of this year as well as the next.

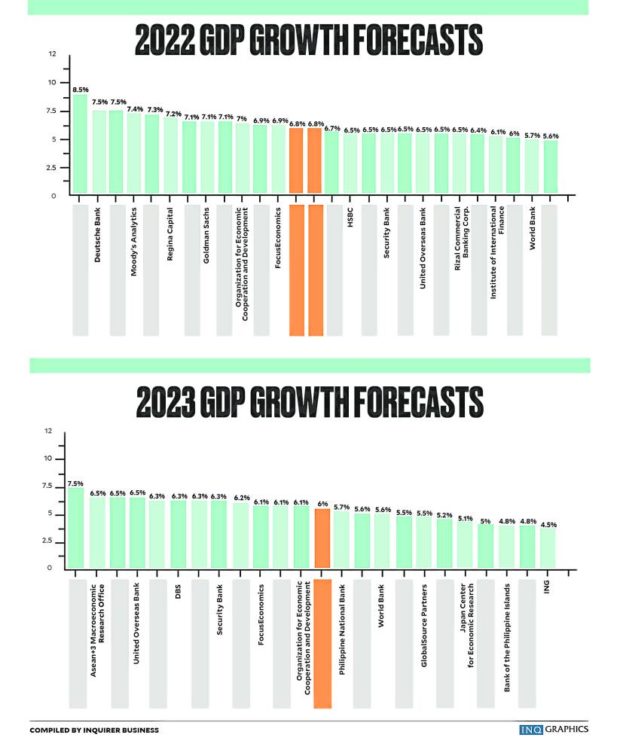

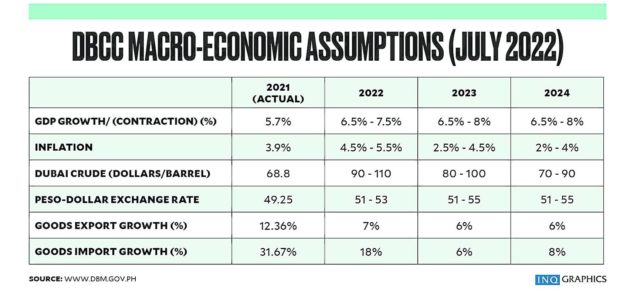

Article continues after this advertisementThe domestic economy regained prepandemic levels, thanks to an 8.3-percent growth rate in the first quarter of 2022. State economists expect to continue this growth momentum for the rest of the year, with the full-year GDP growth assumption slightly adjusted to 6.5 to 7.5 percent (from 6 to 7 percent) “in consideration of recent external and domestic developments.”

Article continues after this advertisementFrom 2023 to 2028, economic growth is expected to be sustained and expanded to 6.5 percent to 8 percent.

In the background of this rosy picture is the crackling fire of inflation.

Forecasting woes

Based on the latest assumptions of the BSP, which advises the interagency Development Budget Coordination Committee (DBCC), the average inflation rate for 2022 is now expected to range from 4.5 to 5.5 percent.

From the previous assumption that inflation will ease back to the target range of 2 to 4 percent by 2023, the BSP and the DBCC now expect this to happen no earlier than 2024. For next year, inflation is now forecast to be within 2.5 to 4.5 percent.

In June, the BSP announced that its latest baseline forecasts have shifted higher, with inflation projected to average at 5 percent in 2022 and at 4.2 percent in 2023. On the other hand, average inflation is also seen to subsequently decline to 3.3 percent in 2024.

From 2024 to 2028, the government assumes that prices of Dubai crude oil, the Asian benchmark that influences prices of petroleum products and one of top contributors to the Philippines’ widening trade deficit, will be within $70 per barrel and $90 per barrel.

Such a range means better for a net oil importer like the Philippines. As of this writing, Dubai crude has fallen to $99.14 per barrel after surging above $100 per barrel for most of the past four months or since Russia invaded Ukraine.

Also, for 2023 to 2028, the Philippine peso is assumed to hover between 51 and 55 per US dollar. The peso recently approached its all-time low of 56.45:$1, over the past five weeks coming from a range of 52 to 53 against the greenback.

Speaking at the BSP-hosted 2nd International Research Fair, Medalla says that while many things are now changing outside the Philippines that are “very challenging,” the BSP’s core policymaking remains guided by forecasts of GDP growth and inflation rates, how its policies can affect these metrics, and the lag between the policies and their effects.

“We, of course, know that our forecasts can be wrong, sometimes very wrong [but also sometimes] in a very pleasant direction,” he says.

In 2015 and 2016, the BSP had forecast that inflation would be very close to the mid-point of its 2 to 4 percent target, or around 3 percent. Actual inflation settled below the target range, at 0.7 percent in 2015 and 1.3 percent in 2016 when GDP grew by 6.3 percent and 7.1 percent, respectively.

“We told the public that we were wrong because import prices … turned out to be much lower than expected,” Medalla recalls.

“People readily accepted our mantra—that monetary policies need not respond to transitory supply shocks,” he added. “And they actually accepted that two years was transitory. Never did we hear that we were behind the curve, that monetary policy was too tight.”

These days, the opposite is happening. Actual inflation is higher than the target range and some economists (to whom Medalla referred as “the noisier part of the gallery”) opine that the BSP is trailing other central banks, especially influential banks like the United States Federal Reserve, in tightening monetary policy.

Since departing from an accommodative stance to support COVID-19 response, the BSP has raised its key policy rate by a total of 125 basis points to 3.25 percent—twice by 25 bps each in May and June and by 75 bps on July 14, in an off-cycle move.

Influencing inflation

Meanwhile, the US Fed has raised its own policy rate by a total of 150 bps in three previous meetings—25 bps, 50 bps, and then 75 bps. However, the American central bank is expected to get even more aggressive with an increase of 75 to 100 bps in its targeted fund rate on July 27.

The result could be a very narrow differential between interest rates in the two countries, which some economists blame for the peso’s sudden decline.

The BSP is quick to point out that currency depreciation against the US dollar is not specific to the peso. However, contrarians also point out that the peso has become the biggest loser among Asian currencies.

“[Now], people don’t want to hear that our tools are not very good in addressing supply shocks,” says Medalla.

“So, I guess we have a lot of educating to do in making the markets accept volatility and live with it,” says Medalla. “We need to do more and more of that gradually over time.”

The BSP chief acknowledges that influencing inflation expectations is just half the battle, especially during episodes of high inflation when central banks cannot afford to look unconcerned or inattentive.

“To properly fulfill its mandates, it’s important that central banks reach their intended audience,” says Medalla.

He also acknowledges that effective communication is key to credibly assure the markets that fundamentals are intact and that appropriate policy actions will be taken when needed in a preemptive fashion.

“In this sense, it has been pointed out that ‘central bank communication can be used to manage expectations both by ‘creating news’ and ‘reducing noise,’” says Medalla.

One of the points that the BSP is mindful of is that global developments like climate change and food security affect the central bank’s forecasts and thus, have implications on policy decisions.

Considering this, Medalla thinks that a central bank might do well to be supportive of other things that are important in operations, such as improving capacity in big data, developing its workforce and providing avenues for regulated entities to participate in green funds.

“While I believe central banks should attend to immediate concerns, we must also keep one eye and devote resources in ensuring that we build our credibility, our skills, and our technological capacities to be equal to the task at measure,” he says. INQ