These economists nonetheless warned of lingering risks coming from new coronavirus strains cropping up like the latest Omicron, as well as political uncertainty when Filipinos choose their next chief executive to lead the country next year as it recovers from the pandemic-induced slump.

While keeping minimum health standards in place to contain the spread of the deadly virus, President Duterte’s economic team was looking forward to moving the country to alert level 1—the least stringent mobility restrictions—at the start of 2022.

The economic managers were also pushing for a change in mindset to consider COVID-19 endemic or the new normal which won’t go away soon, so that Filipinos could go on with their livelihoods and consumption while health and containment measures remain top of mind and a priority.

Socioeconomic Planning Secretary Karl Kendrick Chua—the government’s chief economist—said the sustained safe reopening of economic sectors which had been shut down by strict lockdowns of the past would allow the Philippines’ gross domestic product (GDP) to return to prepandemic levels in early 2022.

Worst recession

By the end of 2022, nominal GDP would reach P21.5 trillion, exceeding the P19.5-trillion worth in 2019, or before COVID-19 struck.

Last year, economic output slid to P17.9 trillion amid the worst annual recession in the Philippines’ postwar history; this year, GDP was expected to rise to P19.4 trillion, still below the 2019 level.

Chua, who heads the state planning agency National Economic and Development Authority, said this year and next year’s gains in the fight against COVID-19 and the socioeconomic ills it wrought would be crucial to minimize the long-term scarring caused by last year’s most stringent lockdowns.

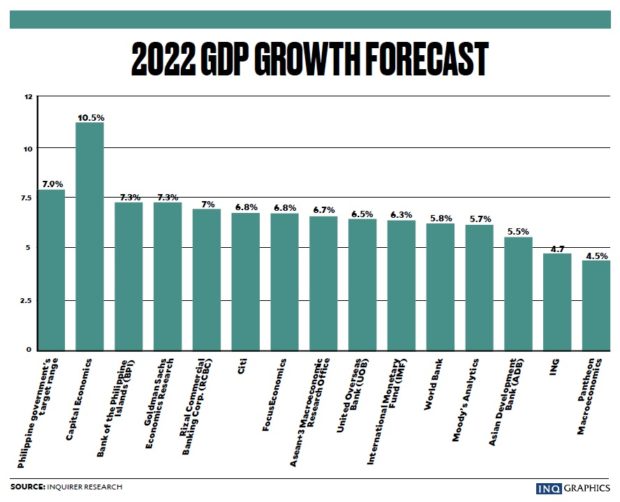

The government targets 7-9 percent growth in 2022—much faster than this year’s goal of 4-5 percent and at the same pace as prepandemic growth rates which had made the Philippines a rising economic star in the region before it took a beating from COVID-19.

Among 2022 GDP growth forecasts collected by the Inquirer from private-sector economists and multilateral development institutions, the UK-based think tank Capital Economics had the highest forecast of 10.5 percent.

Capital Economics Asia economist Alex Holmes explained in an email that their optimism was hinged on an assumption that there would be “no large rebound in virus cases ahead.”

But Holmes conceded that such expectation was “obviously uncertain at the moment and subject to change given the Omicron variant.”

Stronger growth

In a Dec. 2 report, the UK-based think tank Oxford Economics said that “after being hit by major disruptions battling the pandemic in 2021, Japan, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Thailand will all see stronger growth in 2022.”

“Given the scope for catch-up from the worst of the crisis, we expect Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, and Vietnam to all grow by 6 percent or more next year (nearly double the pace achieved in 2021),” Oxford Economics lead economist Simon Knapp said.

Oxford Economics assistant economist Makoto Tsuchiya said in an email that they expect the Philippine economy to grow 6.6 percent next year, although it would be below the government’s goal.

“We expect contained cases and continued relaxation of mobility restrictions will bode well for the growth in 2022, while healthy global demand and easing supply chain bottlenecks will provide support for exports. We expect the momentum to further pick up from mid-2022, when we expect 80 percent of the total population to be vaccinated,” Tsuchiya said.

“However, risks are tilted to the downside, especially around the health situation. Indeed, given the emergence of the Omicron variant and related tightening of border controls, we have nudged first-quarter 2022 growth slightly lower by 0.1 percentage point (ppt). This assumes that the impact of increased uncertainties and travel restrictions are largely confined to the first quarter” of next year, Tsuchiya added.

The said-to-be even more contagious Omicron strain of COVID-19 was expected to slow down recovery in the tourism sector as well as deployment of Filipino workers overseas who send back home billions of dollars each year which drive the consumption-driven domestic economy.

Oxford Economics’ projections showed that the Philippines would belong to the majority of Asia-Pacific economies whose quarter-on-quarter growth rates in 2022 would be faster compared to 2021 averages. The economic team had been monitoring quarter-on-quarter GDP growth rates as these reflected the gradual recovery from quarantine easing.

In the case of the Philippines and Malaysia, Oxford Economics said a loosening of fiscal policy or a still wide budget deficit prioritizing public spending on goods and services would “ensure that economic growth is very strong in 2022.”

Accelerating growth

The Barcelona-based FocusEconomics, which polls economists to obtain consensus forecasts, said in a Nov. 16 report that “growth should accelerate next year, as the country’s stalling vaccination efforts likely finally picked up speed, permitting a relaxation of restrictions and greater certainty for consumers and investors.”

At present, only about two-fifths of the population were fully vaccinated. The government was nonetheless fast-tracking inoculation, especially in areas outside Metro Manila where vaccination rates lagged behind. The national mass vaccination program had also been expanded to include children while giving booster shots to health care workers, senior citizens, and other vulnerable sectors before this year ends to achieve herd immunity.

As such, FocusEconomics’ panelists see below-target 6.8-percent GDP growth in 2022.

For FocusEconomics, “key risks to the outlook include further virus mutations and the outcome of next year’s election, with President Duterte unable to stand.”

The Cabinet-level Development Budget Coordination Committee (DBCC) had similarly flagged a possible slowing down on government infrastructure spending when the election ban on new projects takes effect months before the May 2022 presidential polls.

“In my estimation the political uncertainties and headwinds related to the May election remain under-appreciated; an event-driven risk that will surely put the brakes on government spending (as history shows) and will most likely keep investment spending temporarily at bay,” Miguel Chanco, senior Asia economist at the UK-based Pantheon Macroeconomics, said through email.

But for Dutch financial giant ING, “election-related spending and a sustained push in public construction will help bolster next year’s growth numbers,” its senior Philippine economist Nicholas Antonio Mapa said via email.

“Capping gains, however, will be subdued capital formation and government spending,” which Mapa said “will likely be muted given that the debt-to-GDP ratio is now at a precariously high level.”

As debt accumulation outpaced economic growth, debt-to-GDP — which reflected capability to repay obligations — jumped to a 16-year high of 63.1 percent as of end-September, above the 60-percent threshold deemed by credit rating agencies as manageable among emerging markets like the Philippines.

A global report of ING dated Dec. 2 said that while debt watchers “stood on the sidelines” in 2020 and then began flagging risks in 2021, “in 2022, we believe the warnings will result in actual downgrades.”

“The Philippines is top of the risk list, but we also have some concerns about Indonesia and India, which are on the cusp of dropping to high-yield status,” ING said.

A credit rating downgrade would make borrowings more expensive for the Philippines. Amid the pandemic, the Philippines was able to borrow more at concessional rates to finance COVID-19 response due to the investment-grade credit ratings it currently enjoys.

Also, Mapa said that “capital formation will be constrained in the near term ahead of the elections (awaiting outcome) and as both households and firms await to see if the recent bounce in growth is sustainable.”

“The jury is still out on whether the Philippines can post sterling growth numbers sans favorable base effects,” said Mapa, as he projected 4.7-percent GDP expansion next year, among the least optimistic among forecasts collected by the Inquirer.

Chanco agreed that consumers would be on wait-and-see in 2022 as “the rebuilding of the massive savings lost since the start of the pandemic will weigh on spending decisions for most of next year.” Chanco’s growth forecast for 2022, at 4.5 percent, was the lowest in the Inquirer’s poll.