As we celebrate Mother’s Day tomorrow, what better way to mark the occasion than to honor architecture inspired by moms? History tells us that there are numerous architects who built homes for their mothers in the early part of their careers. The ’50s and ’60s, in particular, have seen the creation of domestic dwellings lovingly designed by modernists for the women who raised them.

Here are some of the most interesting architectural works that express the love of architects for their mothers.

The mural was designed and originally painted by Harry Seidler and reflects the color scheme used throughout the house.

Rose Seidler House

Completed in 1950, the Rose Seidler house launched the career of Harry Seidler in Australia.

A European by birth, the architect had no plans to live in the Land Down Under until his mother requested him to build a house for her in Sydney. Having just finished training under Walter Gropius, founder of the Bauhaus movement, Harry Seidler seized the task of designing his mother’s home as an opportunity to apply his modernist ideals.

The Seidler House was quick to raise eyebrows among the locals. Even during its construction, neighbors would do a double take at the house that sat in the middle of a bushland. There were six doors leading to the house interiors. One bathroom was lit only from above by a skylight, a new idea at that time that left the building inspector confused and bewildered.

What enchanted visitors to the house, however, was the mural created by the architect himself on the sun deck. Abstract and colorful, the artwork reflected the modernist influences that had taken shape in Harry Seidler’s mind during a stint in Brazil. This piece was to be the defining space that made the house famous, along with modernist furniture either custom-made or brought by the architect from New York.

The house defied the suburban nature of most Australian homes during that era. Originally planning to stay in Australia until the completion of his mother’s house, Harry Seidler ended up staying for good due to the successful feedback on his work. Today, the house belongs to the Historic Houses Trust and is open to the public as a museum celebrating modern architecture in Australia.

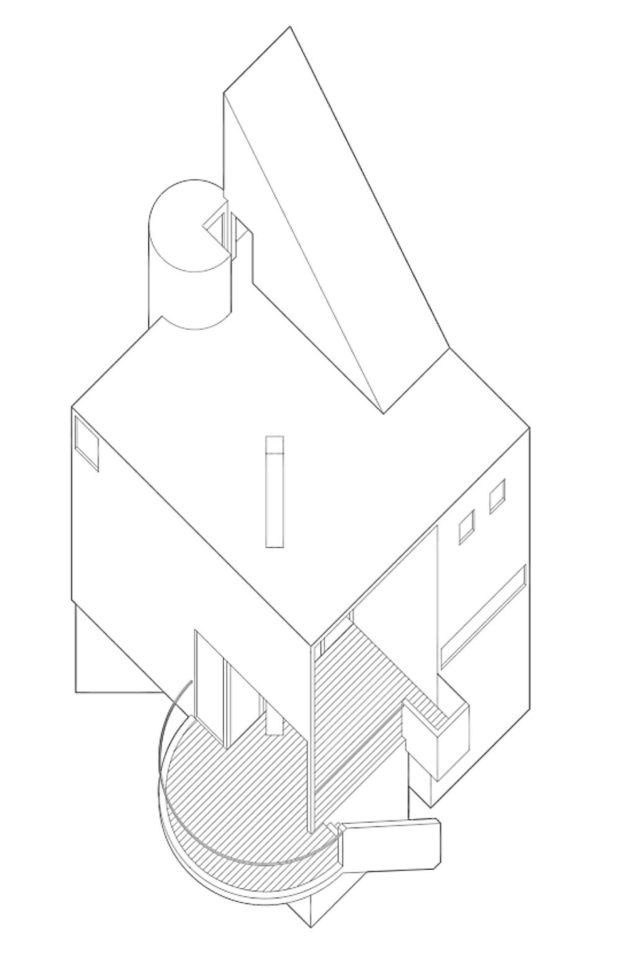

The Gwathmey Residence is sculptural in appearance, paying homage to the works and ideals of Le Corbusier.

Robert and Rosalie Gwathmey House

With a painter dad and a photographer mom, Charles Gwathmey was certainly raised in an artistically inclined home.

In 1965, the young Gwathmey, who was not even a licensed architect at that time, designed a house for his parents—his first project, at that. His parents’ trust allowed Gwathmey to make his mark in the world of architecture.

Costing no more than $35,000 during its time, the Gwathmey Residence and Studio in Amagansett, New York, reflected Gwathmey’s love for modernism. Finding inspiration in Le Corbusier’s works, the house is characterized by solid shapes and small windows. Its creator wanted the building to look like a sculpture, molded out of a single mass. The building took into consideration daylighting and site orientation. The house became a summer residence for the family, but it also served as Charles Gwathmey’s canvas, which jumpstarted his career in architecture and design.

The Gwathmey Residence and Studio was completed in 1967. By then, Gwathmey had already set up his own design practice with a partner in New York City. Later on, he was commissioned to design the homes of famous figures such as Jerry Seinfeld, Steven Speilberg and David Geffen. Of all his works, however, it was his parents’ house that put him on the map. The Gwathmey Home is valued at $9.25 million today and is being sold on the market after having been carefully restored by its previous owners.

Vanna Venturi House

Built in 1964, the Vanna Venturi house went against the style of its times. It is considered the first postmodern house, featuring complex and contradicting forms. Designed by Robert Venturi, the house was meant for his mother’s use and was built at a time when Modernism was still the norm.

The house intentionally breaks formal symmetry with its non-uniform windows. The classic gable roof is reinterpreted as a split form, with the chimney poking out in the middle. Inside, the rooms forego the traditional layout of corridors and rooms. Instead, the spaces have limited partitions between them.

The Venturi house is considered the pioneer of Postmodernism. With his mother for a client, Robert Venturi was able to explore new ideas against the norm. A mother’s love for his son truly can push boundaries and revolutionize the world.

Sources: Sydneylivingmuseums.com.au, Wsj.com, The1960sproject.com, Archdaily.com, Carol Highsmith via Wikimedia Commons, Kyle Miller via the article “Nine Lies” (Offramp 9 Spring/ Summer 2015 by SCI-Arc)