Organic agriculture in PH: No funding, no plans

An organic trial farm of the Dumagat tribe in Koloka-koloy in Puray, Rizal. (Photo by Masipag)

MANILA, Philippines—The Philippines institutionalized organic agriculture through Republic Act No. 10068, or the Organic Agricultural Act of 2010.

The law was recently amended by Republic Act No. 11511 which introduced these provisions:

- Nationwide educational and awareness campaign on the benefits of consuming organic products

- Adoption of the Participatory Guarantee System (PGS) as a community of group-based certification process, other than third party certification of organic products

- Protection of organic resources against contamination by genetically engineered organisms including crops, livestock and poultry and marine products

- Access to marketing by organic producers to ensure decent prices which would ensure organic ventures are profitable and sustainable

While these measures are most welcome, a critical gap exists between the amended law and its implementing rules and regulations (IRR).

Philippine laws and the International Federation of Organic Agriculture Movements (IFOAM) provide that “organic conversion” starts when a farmer stops using chemicals and concludes with certification of his farm to be 100 percent organic, or chemical-free, after a rigorous process.

IFOAM and Asian Regional Organic Standards (AROS) for market-mandated certification require about three years of zero chemical use.

In short, the Philippines needs an organic agriculture program that allows and promotes a gradual, calibrated reduction of chemical inputs and progressively transitions to a more robust or fully organic regime.

Legal vacuum

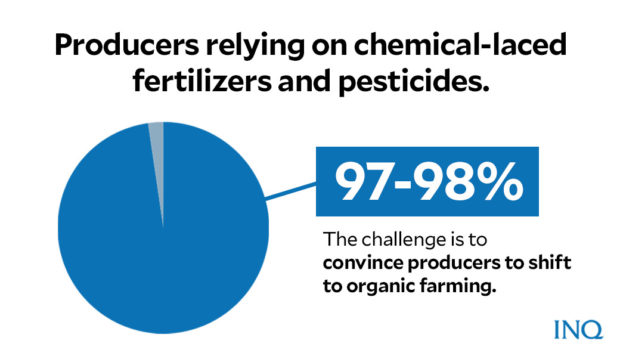

There is currently no clear program and funding for the transition to organic agriculture.

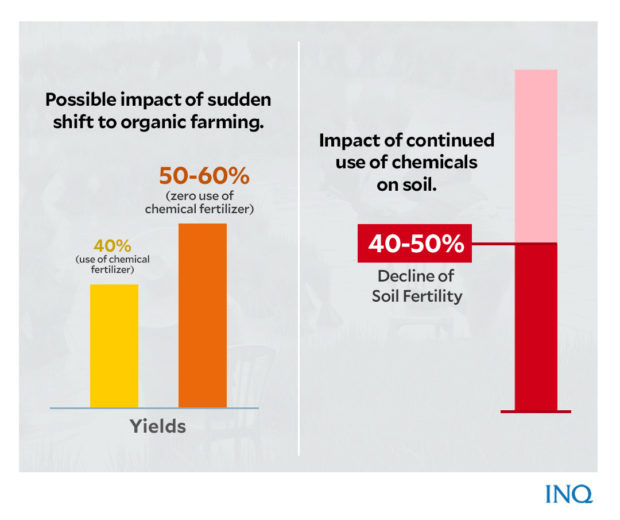

Transition is necessary because if all farmers suddenly adopt zero chemical use, yields may drop to 50 to 60 percent.

As a result, food supply could be at risk unless the country imports 5 to 6 million tons of well-milled rice that would cost P175 billion to P210 billion at P35 per kilo of rice.

An effective organic farming program must recognize actual conditions in the field and support a movement to shift from chemical-based production to organic and ecological farming methods and value chain.

Building up soil health using crop or weed biomass recycling only is slow. To arrest yield decline, voluminous amounts of composted organic fertilizers or vermi-composts, which are not readily available in the fields, should be applied.

Crop-weed biomass for recycling (biomass should not be burned) will also be reduced because along with economic yield reduction goes the non-economic yield or biomass. Chemical fertilizer (NPK) may be applied, together with micronutrients and farm-produced compost or humus, under a “balanced fertilization” regime.

We emphasize farmer-made compost or humus, because farmers buying it will need about P7,000 per hectare (PhP350/bag of 50 kilos x 20 bags). That is too costly and unaffordable too!

Turning wastes into assets

Support may be through bulk procurement of manure (poultry, hog, cattle) in the locality or neighboring towns. Municipalities must also encourage poultry or hog growers to sell manure only to farmers in their towns.

LGUs, under the “Sagip Saka” law, may gather or buy these manure cheaply and convert them into composted organic fertilizer for free or for distribution to farmers at cost.

Organic inputs, like seeds and planting materials, must also be provided to farmers to facilitate the transition process. For sustainability, farmers must be trained to produce and save their own seeds.

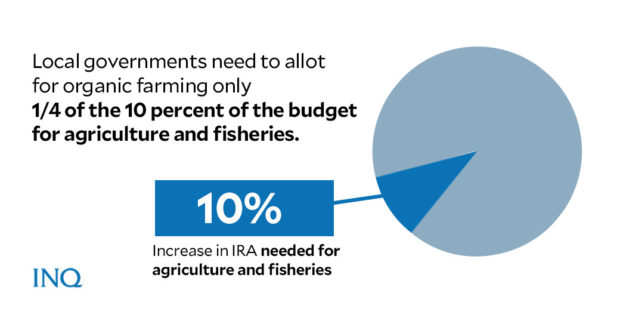

Starting in 2022, DA and LGU funding will be significantly influenced by the Supreme Court’s ruling on cases that increased LGU share in national taxes by 27 percent.

It is imperative that LGUs now devote at least 10 percent of their increased Internal Revenue Allotment (IRA) to agriculture and fisheries, including the devolved extension services, with at least one-fourth of the IRA earmarked for organic agriculture.

To lighten farming work, each village must have a foundry shop (with welding machines, acetylene torch, grinder, cut off or electric driven driller) so that farmers can locally repair, improve and even manufacture farm tools and equipment like grub hoe, wheelbarrow, spade, rake, bolo and carts to be powered by engines or pulled by farm animals.

Second stage

The second transition entails moving farming systems from mono-cropping, or intensified or specialized farming, into bio-diverse or integrated farming systems.

Organic agriculture is a diversified enterprise. Synergy among component activities occurs, as there are complementary and supplementary relationships among farming practices and components involved—manure from livestock made into compost, non-marketable or excess crop biomass is fed to animals to save on expenses on feeds.

There should be various crops planted as companion or inter crops or as sequence and rotation crops to address abundance or lack of nutrients and pests.

‘Bahay Kubo’ seeds

Sadly, farmers have lost even their Bahay Kubo seeds and traditional culture of growing health-promoting vegetables.

The DA and LGUs must revive “Bahay Kubo Cropping” and farmers must be provided with seeds and planting materials.

Farmers should have at least one or two cattle or carabaos to provide farm power and serve as sources of manure for composting. We have optimized liquid fertilizer production from farm input-amplified cattle manure. A subsidy or credit support program must also be designed and funded to facilitate these actions in the transition to organic agriculture.

The third crucial factor is significant investment in research, development and extension on organic conversion technologies, which address the transition processes, steps and procedures to facilitate the conversion stage, or zero chemicals.

Pure and adaptive research on Organic Agriculture in Transition must be funded by the Bureau of Agriculture Research (BAR) of DA and the Philippine Council for Agriculture, Aquatic and Natural Resources Research and Development (PCAARRD) of the Department of Science and Technology (DOST) with the proactive participation of growing numbers of organic agriculture scientists.

During the entire period of transition from chemical-based to certified organic agriculture, the needs and concerns listed earlier must be scientifically tackled and proactively programmed and funded by DA, other concerned national agencies and LGUs.

Motivating farmers to shift to organic agriculture requires not only science-based technology and meaningful funding support, but also an educational and awareness campaign among consumers on the health and ecological benefits of consuming organic products.

Through demand-led approach, consumers must regain consciousness on the real but often hidden costs of chemical agriculture to our health and planet’s ecosystem.

Planetary Health Diet

This calls for Planetary Health Diet (PHD), which consists of safe, nutritious, health-promoting and medicinal foods mainly from vegetables, fruits, herbs, pulses and green salads. In short, PHD is plant-based.

Organic agriculture plays a key role in PHD as the saying goes: “Let be thy food be thy medicine.”

Consuming pesticide-laden or toxic foods weakens the immune system and makes us vulnerable to fungal, bacterial and viral infections, which is especially relevant in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Also, pesticides taken at non-lethal dosage expose us to cancer-causing free radicals .

Woke consumers must then be translated into a healthy and safe food consumption-led demand that will lead to changes on the supply side or more farmers growing crops and raising animals the organic or agro-ecological way.

Third stage

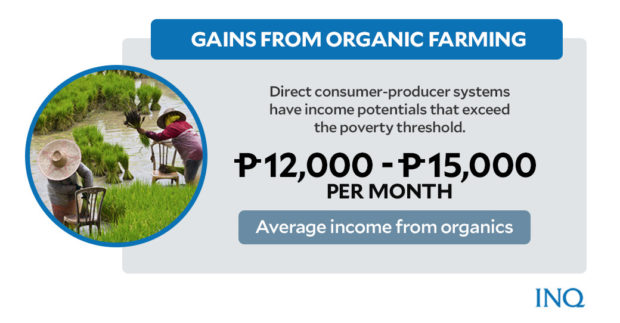

Under the scheme, direct product users—restaurants, hotels, caterers, processors and other institutional consumers—will buy their daily and weekly produce or raw material requirements from organic producers at a fair price.

Thus, a vigorous nationwide campaign must target and include government, educational, religious and food consuming institutions.

Government agencies and instrumentalities, including LGUs, should consider direct organic produce procurement, as provided for in the Sagip Saka legislation, during disasters or pandemics and for feeding programs for children, the poor, elderly and persons with disabilities.

Big corporations, religious and civil society organizations and small or medium-scale enterprises may also provide their employees with organically grown healthy foods in their establishments or as income supplements. Taken altogether, these nutrition-boosting initiatives will create a bigger demand for organically grown foods.

Local government officials harvest lettuce in an organic farm in Maguindanao province.

What’s next?

In the last ten years, we have witnessed the poor implementation of RA 10068 and its limited impact on farmers’ productivity and incomes.

Moreover, we continue to suffer from the continuing adverse impacts of chemical agriculture on our food nutrition and health security and its serious threat to ecology and climate resiliency. It is imperative to have a faster transformation of the dominant chemical agriculture system and its transition to an organic farming regime.

For these to happen, these steps have to be taken:

- Conduct a performance audit of the Organic Agriculture Program from 2010 to 2020

- Prepare an Organic Agriculture Road Map for 2022 to 2028 with the objective of transforming at least 20 percent of chemical-fed lands into “organic agriculture in transition” areas

- Bring 5 percent of all farm lands to fully organic level

- Give priority to transforming single commodity-based chemical agriculture into integrated, area-based organic and ecological farm system

- Revive and activate the “One Organic Movement” to serve as the “united voice of the organic agriculture sector.”

- Establish a strong program on Organic Agriculture in Transition with at least P10 billion in funding which could be increased as LGUs get bigger national tax shares.

To achieve these, budget items would be needed for these:

- P1 billion for 1,000 foundry shops worth P1 million each

- P2 billion in recurring budget for organic seed production and planting materials

- P2 billion for materials to make composts and organic fertilizers

- P2.5 billion for small animals, native chicken or ducks

- P2.5 billion for cattle, carabaos

TSB

(Editor’s note: This report has been culled from papers prepared by former agriculture secretary Leonardo Montemayor, Dr. Teodoro M. Mendoza and Pablito Villegas on organic agriculture. The papers were submitted as inputs in the DA and private sector-led round table online discussion on organic agriculture last April 30)