The human environment

Church at Horizon Manila. Landform architecture allows the development of buildings that can also be engaged as open landscapes.

(First in a series)

Climate change continues to be the single, most important long term global concern, even as we all face the current pandemic. This week, world leaders convened a climate summit to pledge new targets and reinforce existing ones to reduce their emissions. This was in preparation for the next world summit in November.

Our roles as architects and planners to provide system-wide and comprehensive solutions to not just mitigate but also improve our built environment become increasingly important in the world we live in. How do we develop our human environment? How can we make this world we live in a more suitable and beneficial habitat for homo sapiens and our web of interrelated species?

Beyond my personal musings and internal hypothesizing, we’re currently exploring some of these ideas in the work we’re doing. They range from the immediate to the societal, from human to environmental concerns.

A sense of belonging

While we constantly strive to design for our five senses of sight, hearing, smell, taste and touch, we also need to design spaces that enhance our sense of belonging. It is a sense that we have developed over hundreds of thousands of years even before the first extant member of our species. This is the sense that has allowed us to develop our culture and civilization and spread to almost all regions of the world.

Our sense of belonging constantly makes us search for channels to connect with one another. We require communal experiences that bond us together and look for the presence of other people in our living spaces. We congregate and mingle even for no reason, and we fear or avoid empty and bare spaces. We feel anxious in empty halls and corridors, empty and dead streets.

As we strive for the development of 15-minute cities, we must be aware of how we can make pocket neighborhoods communal and conducive to personal movement and exploration. Expand points of gathering beyond nodes and centralities towards corridors of activity that spread out and activate our streetscapes. Our streets are not just channels for movement but part of a web that can be stimulated and livened by human activity.

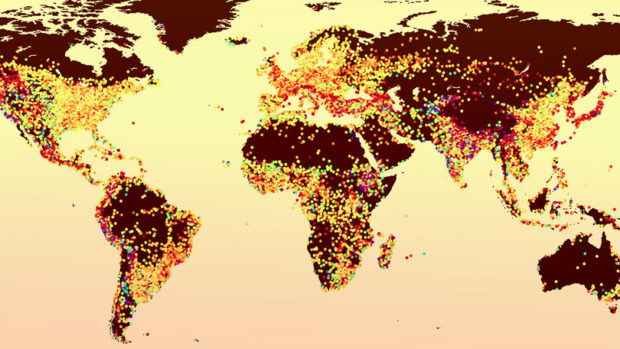

World map of the intensity of the urban heat island effect in 30,000 cities around the world from Eos. org

We need to build community spaces that emphasize inclusion. The community builds for the community. Building is not just an activity that stops when construction ends but can continue as the broader community contributes to its development. Architecture is only the scaffold upon which we build our communities.

Urban habitats

Our cities in many ways are deserts—concreted barren land that is warmer than surrounding areas that radiate heat and continuously drain our aquifers. Large concentrations of dust and surface runoff contribute to growing areas of polluted and infertile land. Poor biodiversity mean that fewer species are existing in habitats that would otherwise be home to so many more species of plant and wildlife.

Humans evolved to settle near bodies of freshwater—in river deltas and plains, in valleys and plateaus. For much of history, our cities required adjacency to fields and pastures, spaces that would provide access to nature and our life-giving earth. We are organic creatures made to live in our own habitat.

Green spaces in our cities are almost like oases in a desert. They are few and far between, and where they exist, they are disconnected and isolated. We need more tree-lined streets, but we also need ground space for public activity. The further development and acceptance of green streets can help renaturalize our cities. They allow for not just permeable surfaces to build up groundwater and reduce runoff, but also more ecologically diverse streetscapes that can better accommodate wildlife.

We can live in river cities, garden cities, and forest cities. Why are we living in a desert city? (To be continued)