The Philippines has become the world’s top rice importer for 2019 with orders expected to reach 3 million metric tons by the end of the year, according to a US Department of Agriculture report. (Inquirer File Photo)

(Second of two parts)

The clear but unexpected winners from the rice tariffication law have been the market intermediaries—the palay traders and millers, wholesalers, retailers, importers and other middlemen who operate between the farmers and the consumers.

RTL proponents had theorized that the unimpeded entry of cheap imports would bring down retail prices for consumers. Free and open competition among market players would supposedly ensure that consumers would get the best possible price for their rice.

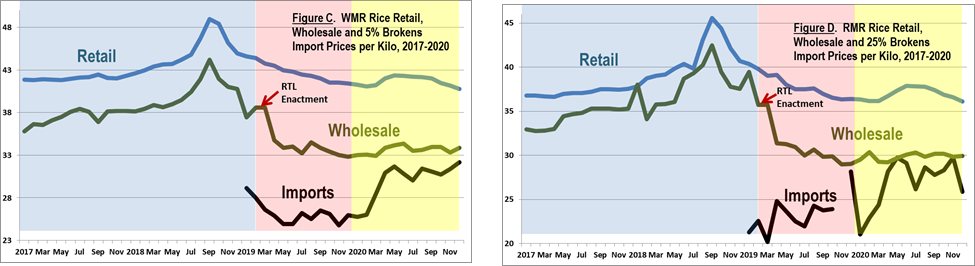

Clearly, this has not happened. Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) data show that, while wholesale prices did go down following the enactment of RTL, retail prices did not decrease proportionately and the margin between wholesale and retail prices actually increased. In other words, middlemen pocketed most of the gains from cheaper imports while giving only loose change to consumers.

Between 2017 and 2018, the average margin between wholesale and retail prices for well-milled rice (WMR) was less than P5 per kilo. In 2019-20, the margin increased to around P8 per kilo, because retail prices remained relatively steady even as wholesale prices went down. A similar trend was evident for regular-milled rice (RMR), with margins growing from around P3 before RTL to P6-7 per kilo after the law’s enactment.

Computations indicate that wholesalers and retailers gained an extra P35 billion in 2019 and another P43 billion in 2020 even as farmers reeled from P56 billion in losses during the two-year period. In other words, the sacrifice that farmers endured did not result in benefits to consumers but instead lined up the pockets of middlemen.

Importers’ heyday

Meanwhile, importers had a heyday in 2019 with imported rice with 5 percent broken grain landing at P8.61 per kilo below prevailing wholesale prices. Margins for imported rice with 25 percent broken grain averaged P6.49 per kilo. Overall, importers had a windfall gain of P24.9 billion during the year.

In 2020, importer margins declined significantly due to the uptick in international rice prices. Still, importers managed to earn an extra P6.51 billion.

What was surprising in 2020 was that wholesale prices did not react to the movement in import prices unlike in 2019. This could indicate a reversal of roles—while palay trader-millers were at the mercy of importers in 2019, they became the price leaders in 2020, outpricing imports at the wholesale level. This, however, came at a price as trader-millers appear to have foregone P20 billion in profit margins during the year.

It seems ironic that the market had to rely on palay traders to keep rice prices steady while import prices crept up in 2020. Still, the analysis shows that money was simply changing hands between market intermediaries, while leaving farmers in the dust and consumers with little to be happy about.

Deregulation was supposed to free the government from expensive subsidies to prop NFA’s operations. Relegating the agency to buffer stocking was also intended to reduce graft and corruption in the importation and sale of rice.

The NFA, however, has not been totally relieved of its costly market intervention functions despite the prohibitions imposed by RTL. It was forced to buy palay above market costs to prop farm gate prices when large volumes of imports flooded local markets. NFA is further being obligated to supply rice to the military and other government units, even though it should be keeping its stocks in reserve for calamities.

Buying palay from farmers, milling it into rice, and then selling the rice at government rates is inherently expensive. In fact, it is more costly than simply importing rice and selling it to consumers even at subsidized prices. NFA now loses about half of its capital during each turnover. At this rate, its P7 billion annual procurement budget could dissipate into losses in just one year.

While opportunities for corruption within NFA may arguably have been lessened, there has been a perceptible rise in profiteering and predatory behavior by private players who assumed most of NFA’s roles in the market.

Sacrificial lambs

In the past, NFA incurred losses in order to supply cheap rice to poor consumers and keep retail prices steady. Under RTL, market intermediaries pocketed most of the gains from cheaper imports for themselves. Farmers and consumers became the sacrificial lambs so that middlemen could preserve their profit margins. Importers even undervalued their shipments and deprived the government of up to P5 billion in tariff revenues, and shortchanged farmers of equivalent support, in the first two years of RTL.

On the positive side, the government generated almost P30 billion in import tariffs in the first two years of RTL, whereas NFA usually brought in rice on a tax-exempt basis in the past. All of that money, however, is earmarked for additional support programs for rice farmers and cannot be considered as incremental income for the government.

RTL was supposed to induce a radical shift in the decades-old bias for the rice sector, particularly in the allocation of budgetary support. Expensive programs targeting self-sufficiency were expected to give way to interventions that would instead focus on improving productivity and profitability while freeing funds for other equally important and needy sectors such as corn, poultry and livestock, fisheries, coconut and high value crops.

Ironically, the government ended up allocating disproportionately more funds for the rice sector as a result of the disruptions caused by imports following the enactment of the law. Aside from RCEF, billions were used on cash transfers, seed and fertilizer subsidies, crop insurance, NFA procurement and other interventions exclusively for rice farmers.

Even then, there are worrisome indications that funds are not being used wisely and cost-effectively. In 2020, the DA spent an estimated P1.35 for every P1 worth of additional palay output that it generated from its RCEF, Rice Resiliency and other supplemental programs, even after discounting the effect of typhoons and other calamities.

The DA has been implementing programs and spending money without a Rice Road Map, which—under the RTL—should have been completed in August 2019. Moreover, the DA has not conducted legally mandated consultations with farmers and other stakeholders.

The National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) dilly-dallied for nearly a year before submitting its computation of the out-quota tariff-equivalent for rice, a simple exercise that should have been completed within the 45-day period prescribed by the RTL. Until now, the World Trade Organization (WTO) has not yet confirmed the country’s new tariff rates for rice due to the DA’s failure to submit the guidelines for the allocation of the Minimum Access Volume (MAV). The deadline for this was in April 2019.

The RTL raised the out-quota bound tariff for rice imports to 180 percent, or the computed tariff equivalent, whichever was higher. This tariff would be the maximum rate that could be imposed on imports of rice originating from non-Asean countries and outside the MAV.

Inexplicably, however, the out-quota tariff was unilaterally set to an applied level of 50 percent without any public hearing or consultations with stakeholders as required by law. Nor was there—as required by RTL—an explicit order from the President to adopt this low applied rate.

In 2020, the Philippine International Trading Corporation (PITC) tried to import rice upon the prodding of the DA despite the absence of a declaration of a rice shortage. PITC was forced to invalidate the results of a completed international bidding, after the Department of Budget and Management (DBM) held that there was no legal basis and no budget cover for the importation.

The DA has temporarily suspended the issuance of Sanitary and Phytosanitary Import Clearances (SPSICs) as a belated response to the drop in palay prices arising from over-importation. This contravened the clear intent of the RTL to remove as many restrictions as possible on rice imports.

In fact, the law provided that SPSIC applications should be approved within seven working days from submission of complete requirements. Imposing SPS restrictions for reasons other than pest, animal and food safety concerns is also prohibited under WTO rules.

Vulnerability

The DA has repeatedly rejected appeals from key stakeholders to temporarily impose general safeguard duties to stem the inflow of imports.

This trade remedy was added to WTO rules precisely to help countries cope with market disturbances arising from excessive imports. Its application is allowed by Republic Act No. 8800 (Safeguard Measures Act). Yet, the DA opted not to use this legal remedy and, instead, exposed the country to a dispute in the WTO with the illegal use of SPS measures.

RTL proponents had argued that the international market would be a superior guarantee for the country’s food security, since any domestic shortage could be addressed by imports.

The COVID-19 pandemic, however, has exposed the vulnerability of international food supply systems, particularly in a commodity sector like rice where there are relatively few exporters but many importers dealing with a small volume of traded stocks.

Natural calamities, disputes among countries over water, and even political turmoil could easily affect the capacity of exporting countries to supply rice. Shortages in large importing countries could in turn put pressure on supply and lead to sudden spikes in prices in international markets.

Imports will definitely be needed for as long as domestic production is not sufficient. If imports are excessive, however, the country could become too dependent on foreign suppliers and vulnerable to external supply and price shocks.

Nor does it make sense to entice farmers with subsidies so that they will continue planting and expanding production even as we keep the floodgates open for unlimited imports. This will only result in supply gluts and recurrent downswings in palay prices, leading to more losses for farmers and possibly forcing many of them to downscale their production or leave rice farming altogether. Government will then have to fork over even more money to convince the remaining farmers to continue planting, or give up and allow our food sufficiency levels to deteriorate to precarious levels. In the end, the country’s food security may be irretrievably imperilled.

The analysis showed that the RTL has grossly failed to deliver on its promises. It is not working as originally planned and advertised. In the process, farmers are getting hurt, consumers are not gaining anything, and market middlemen have become the unintended beneficiaries of the law. Government has been forced to spend a lot of money to address emerging problems, but with very little impact.

Some groups cannot be faulted for demanding the outright repeal of the law and the reinstatement of quantitative restrictions on rice imports. Farmers are in a worse position now than before RTL. Many would prefer to revert to the old system, with all its deficiencies and pitfalls, than hold on to promises that cannot be fulfilled.

Abrupt move

RTL proponents insist that it is too early to judge RTL, that the problems we are facing are mere “birth pains” and that we must ask farmers and consumers to wait for three years before we can start reviewing and tweaking the law. That is totally unfair and irresponsible.

In fact, those who pushed RTL and made all those promises and assurances should be made immediately accountable for the billions of pesos in losses that farmers have incurred as a result of the abrupt liberalization of the rice industry.

We have seen that prices for consumers will not go down just because we allow more imports to come in. Government must step in to ensure that the gains from liberalization are equitably distributed along the rice value chain.

The government needs to craft a clear and effective strategy to balance imports with local supply to prevent acute shortages on one hand, but avoid excessive supply gluts on the other, while farmers are finding ways to become more competitive. It must recast its programs to assist farmers, anticipate instead of just react to problems, and ensure that funds are spent wisely and effectively. We need to revisit the law itself to respond to these challenges. (Editor’s note: Raul Montemayor is national manager of Federation of Free Farmers)

RELATED STORY

FIRST PART: Rice tarrification: A litany of broken promises