Keeping the legacy of historic buildings through architecture

Crafting the ideal, globally-competitive city does not always equate to high-rise buildings of glass and steel. Sometimes, it can also mean embracing the uniqueness of its past.

Vulnerability of historic buildings

To extend the life of historic structures, there are two important details that designers should pay special attention to—first, the architectural intent of the projects, and second, the history of their construction methods.

For example, historic buildings are often characterized by geometric plans and elevations, shallow foundations, insufficient vertical joints, and transversal braces, in-plane flexibility, and the absence of floor slabs. Altogether, these elements can make historic buildings susceptible to repairs even in moderate seismic events.

Given the delicate structural nature of historic buildings, preserving and restoring them should be aimed at protecting not only their artistic and historic testimony but also their future occupants. Hence, interventions should be reversible and non-invasive, using compatible materials that would not alter their original structural concept.

In the case of traditional Ivatan houses, a major earthquake that took place on July 16, 2000 led to varying damages in many historic houses. Combined with the scarcity of lime and traditional raw materials, an immediate response was to use conventional materials and technologies—one of which is reinforced concrete, a modern component incompatible with their original form.

As urgency and scarcity came into play, the historic houses of Batanes could benefit from a “preventive maintenance” or “most retention and least intervention” approach. This means that preserving their original aesthetic, cultural and structural appeal can only be possible with minimal alterations.

Bearing a ‘contemporary stamp’

Preserving and revealing the aesthetic of historic buildings concerning their original forms halt at a point where conjectures emerge. In this case, any necessary restoration work should have distinct architectural compositions that bear a “contemporary stamp.” However, this “contemporary stamp” does not necessarily refer to a physical element. This can also manifest itself through intangible means—particularly by following the concept of adaptive reuse to accommodate more timely uses of historic properties.

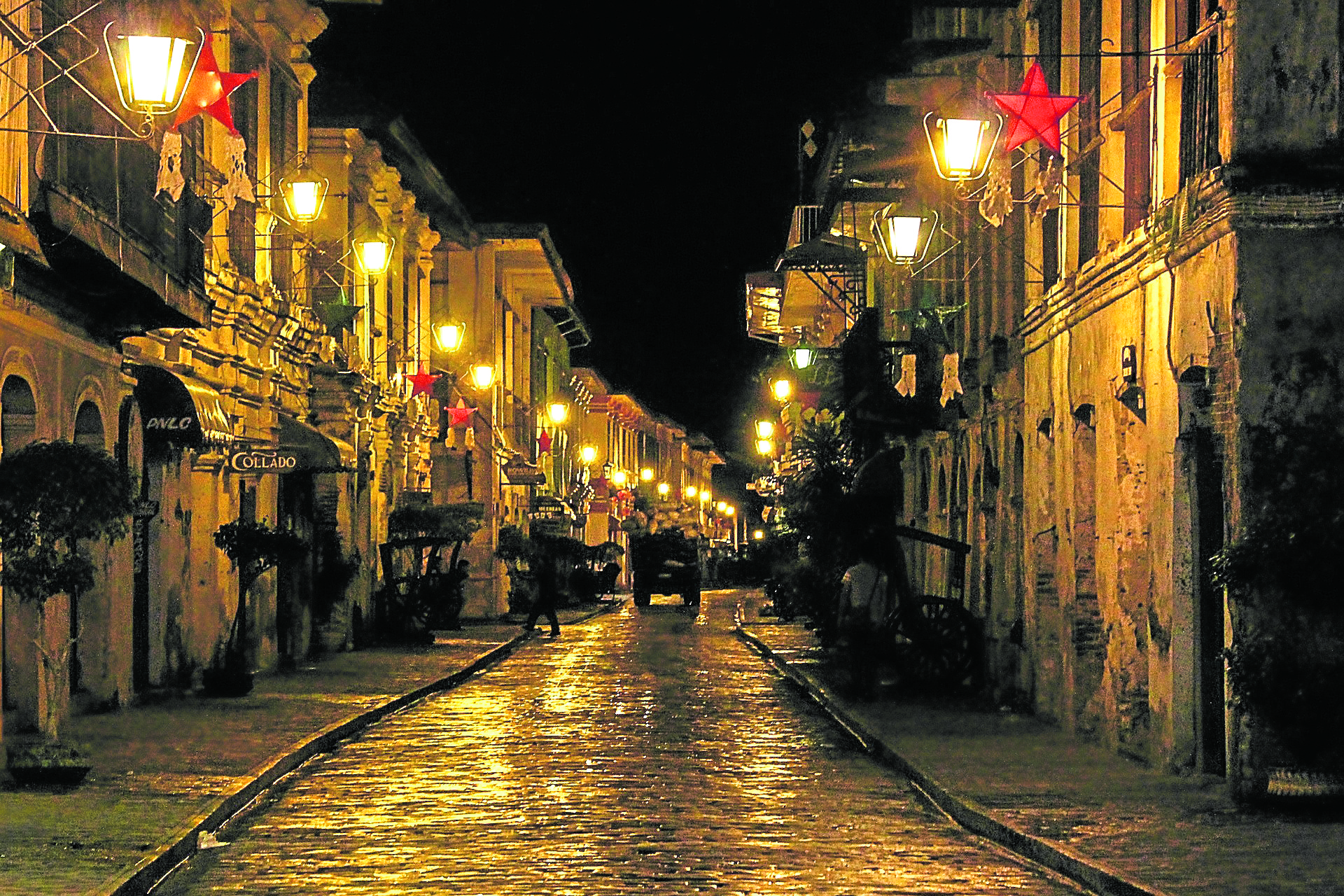

One look at Calle Crisologo in the historic City of Vigan and how it transformed Antillean houses into charming souvenir shops, cafés, bars, restaurants and hotels should be enough evidence how adaptive reuse cannot only preserve an architecture’s historic roots but also attract new activities and more tourists within the area.

Foregoing unity of style

If a building’s significance traverses into multiple eras, then its valid contributions among these various periods should be respected. Hence, achieving a unified look should not be a priority in preserving and restoring historic buildings.

Forgoing the unity of style results in a three-way approach in architectural preservation. First is by revealing a building’s underlying state only justifiable in exceptional instances. Second, purposely eliminated materials should hold little purpose, and third, retained elements should be of great aesthetic, archaeological or historic value.

Aside from completing missing elements, this principle of foregoing unity of style to showcase a building’s development throughout progressing eras should be applied when replacing its missing parts. While replacements should harmoniously integrate with the entirety, they should also be distinguishable from the original form. This way, the modifications will not falsify its historic and artistic evidence, while still embracing its uniqueness.

Colonial-house-turned-events-hall Casa Real in Taguig perfectly celebrates its Filipino, Chinese, Spanish and American influences in honor of the bygone eras, starting from the 1930s. Although it is practically a new structure with its original foundations no longer used, its older elements such as the narra and ipil flooring, gargoyle heads, concrete balusters, as well as its original layout made their way to the house’s final form. Regardless, the rest of the property is now modernized.

Linking heritage with sustainable development

Time plays a vital role in defining both the historic and sustainable characters of the built environment, making them innately linked to each other.

While the historic character is measured backward, sustainable development anticipates the future. This is an important consideration, particularly how buildings respond to resources and possible environmental impact. Such linkage is further strengthened in one of the three pillars of sustainable development, which promises to protect and enhance the environment. Heritage then follows the same course, as historic buildings under architectural preservation promote protective measures against natural and man-made hazards.

Intramuros is now introducing itself as a “sustainable creative urban heritage district” with a vision of promoting urban regeneration, cultural heritage and sustainable tourism. To achieve this vision, the district promotes the “pedestrianization” of major roads for better appreciation of its major destinations, the redevelopment of open spaces for users to reconnect with its historical roots, and finally, the subsidization of socialized housing units for informal settlers residing outside the district.

A one-way street

The architectural preservation of historic buildings is a one-way street. One can only preserve and restore them up to a certain point, and once their limits are reached, specifically when the subjected buildings vanish, there is no chance of getting them back.

Only time will tell how the society will value these historical buildings in the future. But until then, understanding the irreversibility of a lost piece of history, and in this case, in the form of buildings, should bring light to appreciating them at present.

The author manages his own architectural and technology studio helping local and international clients looking for unique, sensible, and diversified design specialties for hotels, condominiums, museums, commercial and mixed-use township developments with a pursuit for the metamodern in the next Philippine architecture