Structures for survival

Man has been through the worst of Mother Nature’s wrath. Epidemics, volcanic eruptions, great floods—these are just some of the catastrophes that have battered history with destruction, losses, and deaths.

People, however, have emerged wiser and better in the aftermath of every disaster. We have learned to reshape our environment to protect us from future havoc. Using the tools and materials available to us, we created structures and buildings to improve our chances of survival in future onslaughts. These responses have greatly improved our chances in the challenges that followed, allowing us to rise above our losses and protect future generations for years to come.

Let us pay tribute to 35 creations borne out of disasters, inspired by the worst experiences but molded with hope. These masterpieces stand as testaments to human mettle and resilience as well as to our never-ending struggle to survive.

The Lazarettos of Dubrovnik was among the first facilities to isolate people coming from plague-stricken countries in the 14th century.

The Lazarettos of Dubrovnik

(1377, Dubrovnik, Croatia)

In 1377, the City of Ragusa passed a law that required all incoming ship passengers to the island to submit to 30 days of isolation, particularly those that came from areas infected by European plagues. Dubrovnik was the first port along the Mediterranean to implement quarantine restrictions, which led to the establishment of “lazarettos” or isolation facilities named after St. Lazarus, the patron saint of lepers. The first was the Benedictine monastery quarantine on the Island of Mijet in 1397, followed by the lazaretto on the Island of Dance in 1430 and in Lokrum, in 1534. The last was built in 1590 at Ploče, the old town’s eastern entrance. Apart from being popular tourist attractions today, the lazarettos of Dubrovnik had also played significant role in the development of medical practices against epidemics.

Sources: Lasta via Wikimedia Commons, www.bbc.com

These structures are some of the remnants of the Lazaretto Vecchio, an island complex that served as the world’s first plague-built hospital.

The Lazzaretto Vecchio

(1423, Venice, Italy)

The site of the world’s first plague-treatment hospital, Lazzaretto Vecchio is an island part of the Venetian Lagoon. In 1423, a leprosarium was constructed on this isle, leading it to be called “Lazzaretto” over time. The island played an important role during the Bubonic plague that ravaged Italy during the 17th century. As the plague could only be controlled by implementing strict quarantine measures, people who started to display symptoms were immediately transported to the Lazzaretto Vecchio. By the 19th century, the island was turned into a military depot. In 1965, it became a dog pound for 30 years. By 2013, the Archeoclub of Venice was entrusted with the maintenance of the historical facility to turn it into a new “Museum of the City.”

(Sources: Powermelon via Wikimedia Commons, www.abandonedspaces.com)

A 1930 image shows the North Head Quarantine Station that protected Sydney from falling prey to European plagues during the early 20th century.

The North Head Quarantine Station

(1832, Sydney, Australia)

Australia began to develop its own facilities to protect its residents from diseases unknowingly transmitted by passengers docking at its wharfs. The North Head Quarantine Station, known as “Q Station” among locals, operated from 1832 to 1834 to screen and isolate disease-stricken passengers arriving by ship. Its importance in epidemic prevention in Australia was recognized by the Quarantine Act of 1932, which aimed to protect the country from the cholera pandemic that then ravaged Europe. Today, the station is a heritage landmark featuring a hotel, conference center, and restaurant complex. The National Parks & Wildlife Service (NPWS) of Sydney carries out guided tours in the area to promote its historical significance.

Sources: The Office of Environment and Heritage via www.qstation.com.au.

Senegal Brick Homes

(1803, Saint-Louis, Senegal)

When European settlers first set foot in Senegal, they called the country in West Africa “the white man’s grave.” To protect themselves, the French, who had numerous troops in the area, began to eliminate thatch-roofed buildings. Beginning with Saint Louis Governor Rue Blanchot, the settlers promoted brick as the choice material for houses. Brick structures proved to be useful in preventing fire outbreaks and were easier to maintain during the outbreak of the Bubonic plague as the brick buildings were simply fumigated while the thatch ones were completely demolished. Overtime, sanitary belts were established in Dakar to prevent and control the spread of diseases.

(Source: www.hindawi.com)

This weir is one of the few remnants of the Old Croton Aqueduct that provided fresh water supply to New York during the 19th century.

The Old Croton Aqueduct

(1837, New York City, US)

In the 19th century, New York was plagued with epidemics of yellow fever and cholera. The unsanitary conditions, coupled with overpopulation, poor sewage systems, and poor public knowledge, led to the spread of diseases which killed many residents. By 1832, people were clamoring for fresh and clean water in the city. Led by Maj. David Bates Douglass, an engineering professor, the Croton River in southern New York was provided with dams, aqueducts and tunnels to channel the water safely to the city. The aqueduct became fully operational on 1842, providing much needed clean water to the citizens of New York. Eventually, a second aqueduct called the “New Croton Aqueduct” was built in 1890 to further supply the city’s water needs.

(Sources: https://aqueduct.org, Beyond my Ken via Wikimedia Commons)

The Modern Sewage System

(1847, London, UK)

While not a building in itself, the modern sewage system put a halt to some of the world’s worst epidemics. In the Industrial Age, London suffered from poor sanitation. While modern toilets and beautiful fountains graced the homes of the rich, public streets were filled with cesspits and flooded drains. Diseases such as cholera and typhoid fever were rampant. Yet the link between poor sanitary practices and diseases was only made in 1847, when the English doctor John Snow proved his theory that cholera was caused by contaminated drinking water. Eventually, new sewage systems were introduced, designed with proper ventilation and water treatment. These practices significantly reduced the occurrence of numerous epidemics over time.

(Source: www.wearewater.org)

Central Park

(1853, New York City, US)

Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted in 1853, Central Park in New York City is one of the most popular attractions of America. Its primary purpose, however, wasn’t to serve as a tourist spot. Rather, it was to serve as the “Lungs of the City”, built for “the sanitary advantage of breathing.” During its inception, New York suffered from tuberculosis and malaria amid overpopulation and cramped housing. Thus, it was believed by many that an open and lush park would help improve public health. Today, the park continues to be seen as a crowning achievement of urban planning, and has set the standard for green spaces in other urban environments.

(Sources: Ajay Suresh via Wikimedia Commons (photo), www.gothamcenter.org)

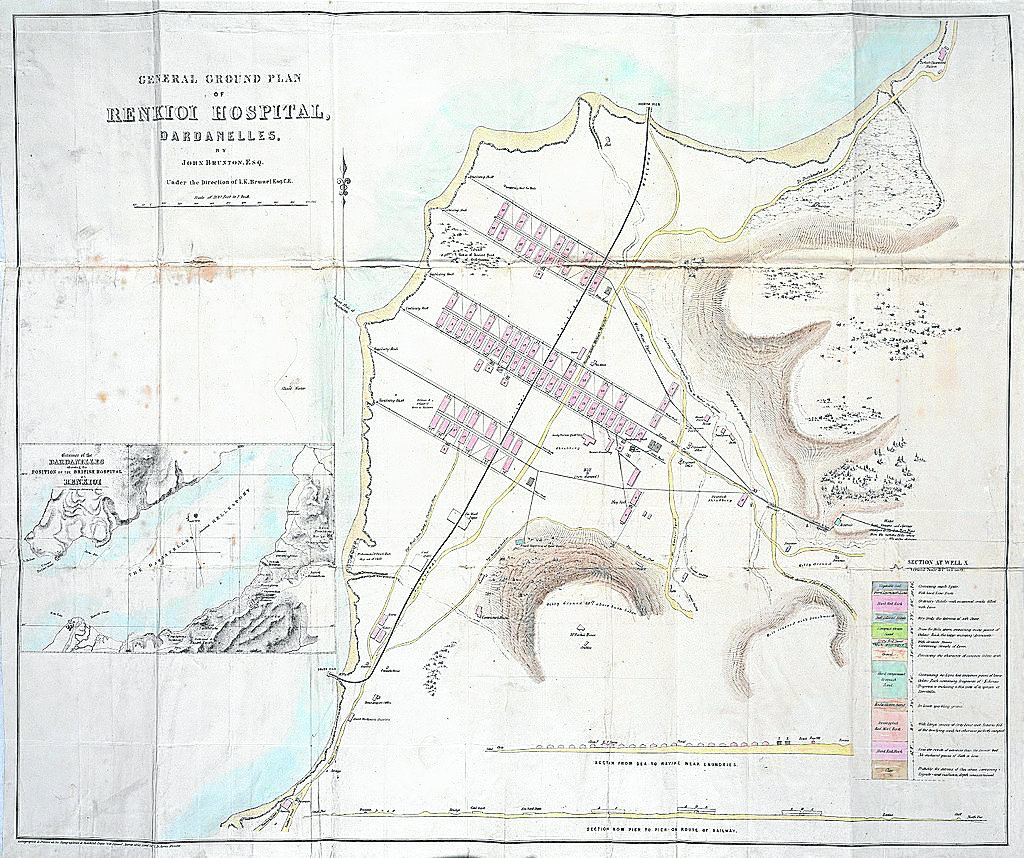

This map of the Renkioi Hospital shows the layout introduced by Isambard Kingdom Brunel that encouraged hygienic practices in building

Renkioi Hospital

(1854, Great Britain)

During the Crimean War, many injured soldiers acquired diseases such as dysentery, typhoid, malaria and cholera. Isambard Kingdom Brunel, an engineer responsible for many modern marvels during that time, was invited to design a pre-fabricated hospital. Brunel had set out to design a unit ward that had hygienic features—sufficient access to sanitation, ventilation, drainage and temperature control—as he believed that such a facility was essential to fight diseases. His theory proved correct when the death rate dropped to only 3 percent from 43 percent during the hospital’s operation.

(Sources: https://wellcomeimages.org, www.harvarddesignmagazine.org)

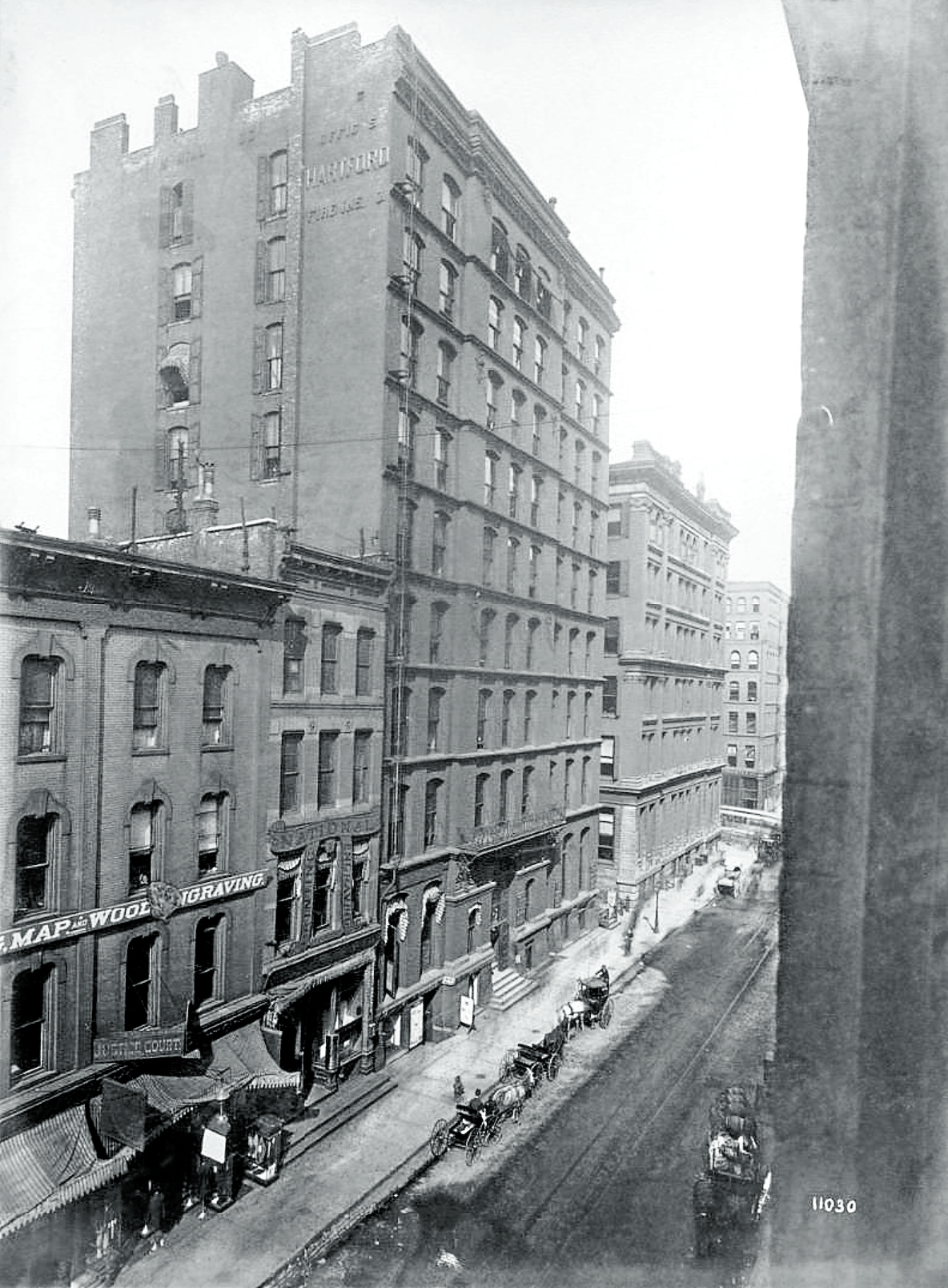

Despite its short lifespan, the Montauk Block of Chicago revolutionized fire safety design in buildings.

Montauk Block

(1881-1882, Chicago, US)

Designed by civil engineer John Wellborn Root and renowned architect Daniel H. Burnham, the Montauk Block building arose a decade after the Great Chicago Fire of 1871. Montauk Block was one of several tall office buildings that were considered the early skyscrapers of history. Two innovations made this project stand out: first, the building’s beams were covered by hollow tile, making them more resistant to fires; and second, the “rail-grilage” technique was introduced to strengthen footings. The Montauk Block was eventually demolished in 1902, to make way for the First National Bank Building. Despite its short life, it left an unforgettable mark on the history of high rise structures.

(Sources: John Taylor of Chicago Tribune via chicagology.com for photo, www.lib.niu.edu)

A photo of the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium shows the cure porch which allowed TB patients sufficient access to natural light and ventilation.

Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium

(1885, New York, US)

Diagnosed with tuberculosis at age 24, Dr. Edward Livingston Trudeau isolated himself in Adirondack Mountains and did his best to get a lot of fresh air and sunshine to regain his health. Thankfully, it worked wonders. After recovering, he poured his energy into researching about the effects of a clean and natural environment in tuberculosis. This led him to establish the Adirondack Cottage Sanitarium in 1885, a facility which introduced a “cure porch” where patients, protected by sliding glass windows, could avail themselves of ample sunshine and fresh air at least eight hours a day. Today, the cure cottages inspired by Dr. Trudeau’s research have stopped functioning as sanitariums when medicine for tuberculosis was finally developed, but many remain well-loved as historic private homes.

(Sources: US Library of Congress Prints and Photographs division via Wikimedia Commons, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov)

Letchworth, the first Garden City, was created to promote living in a healthy environment for city workers.

Letchworth Garden City

(1903, Hertfordshire, England)

This town in England is one of the first garden cities to be built—a concept taken from the ideas of Ebenezer Howard, author of the book “Tomorrow: A Peaceful Path to Real Reform.” Howard’s ideology combined the benefits of countryside environment with metropolitan advantages. He introduced the idea of creating radial communities which were self-sufficient and had limits in terms of population. The Garden City paved the way for others to be built, promoting the idea of healthy living among city workers who were used to the smoke and pollution of the city. Today, the community continues to exist and serve as a suburban neighborhood that reflects Howard’s ideals.

(Source: www.letchworth.com)

This apartment building designed by Peter Behrens finds inspiration in the architecture of tubercolosis sanatoriums.

The Weissenhof Apartments 31 and 32

(1927, Stuttgart, Germany)

Built for the Deutscher Werkbund exhibition of 1927, the apartments designed by the Ar. Peter Behrens was just one of many buildings that were showcased in the Weissenhof estate. What made Behrens’ work unique was that they featured elements synonymous to the sanatoriums built during the 20th century epidemic era. Behrens’ apartment designs was a group of single-, two-, three-, and four-story apartments combined in such a way that the roof of one structure served as the terrace of another. This access to the outdoors was prominent in many modern sanatoriums which favored exposure to the natural environment. Behrens’ practice would also bear a significant influence on one of his protégés who was also famous for following sanatorium-inspired facilities–Le Corbusier.

(Sources: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.go, Andreas Praefcke via Wikimedia Commons)

Lovell House

(1927, Los Angeles, US)

Dubbed as a complete “machine for healthy living,” the Lovell House of Southern California served as a built homage to the health and wellness movement that became popular in the late 19th century. In 1927, health columnist Philip Lovell hired Ar. Richard Neutra to create a home that represented modernist ideals. There were outdoor private areas which allowed the owners to sunbathe nude or to teach kids outside. The kitchen was designed to cater to vegetarian requirements for Lovell’s wife. The house seemed eccentric during its time, but it eventually started the creation of numerous “wellness resorts” that prevail today.

(Sources: www.kcrw.com, Los Angeles via Wikimedia Commons)

Villa Savoye, Le Corbusier’s most recognizable work, represents the modernist movement which was sparked by 20th century epidemics.

Villa Savoye

(1928, Poissy, France)

Villa Savoye, one of the most recognized works of Swiss architect Le Corbusier, represented the pinnacle of the modern movement–an architectural style brought about by the epidemics. Its design represented the architect’s “Five Points” which form his personal architectural approach. These points basically called for pilotis (grid of concrete or steel columns), a roof garden, a free ground plan, horizontal windows, and a free façade. Put together, these elements provided ample ventilation, easy maintenance, abundant sunlight and sufficient distance from the germ-ridden earth. While not an epidemic structure per se, Villa Savoye represents the aesthetics that was borne out of the experiences of the people in times of disease and fear.

(Sources: slate.com, Rory Hyde via Wikimedia Commons)

The Paimio Sanatorium in Finland was designed by Aalvar Aalto to treat tuberculosis patients with dignity.

Paimio Sanatorium

(1932, Paimio, Finland)

Heralded as a “revolutionary hospital” during its time, Alvar Aalto’s Paimio Sanatorium changed the way people treat those afflicted with tuberculosis. In creating Paimio Sanatorium, Aalto treated the building as a “medical instrument” ensuring that it had abundant provisions of daylighting, heating and ventilation. The project also gave birth to Aalto’s famous Paimio chair, which used bent plywood to create furniture that helped improve the user’s breathing. Today, the Paimio Sanatorium remains a prized gem of the medical field. It helped treat tuberculosis patients more humanely during its time.

(Sources: Leon Liao (photo) via Wikimedia Commons, www.architectural-review.com)

ELIZABETH TAYLOR MEDICAL CENTER

(1993, Washington, US)

This center represented a sanctuary for the hundreds of Americans who suffered from HIV and AIDS in the ‘90s. It was one of the few facilities that offered healthcare and legal services without any prejudice to those afflicted. In 2016, the block-long building was redeveloped to include residential, retail, and health services. Managed by the non-profit group Whitman-Walker Health, the project was undertaken by the German architect Annabelle Selldorf and her firm. Selldorf introduced a large mural on the building façade to ensure that the building will always catch the attention of passersby. Today that society is more accepting of people of all races, gender and background, the center’s value in medical history can be finally recognized.

(Source: www.whitman-walker.org)

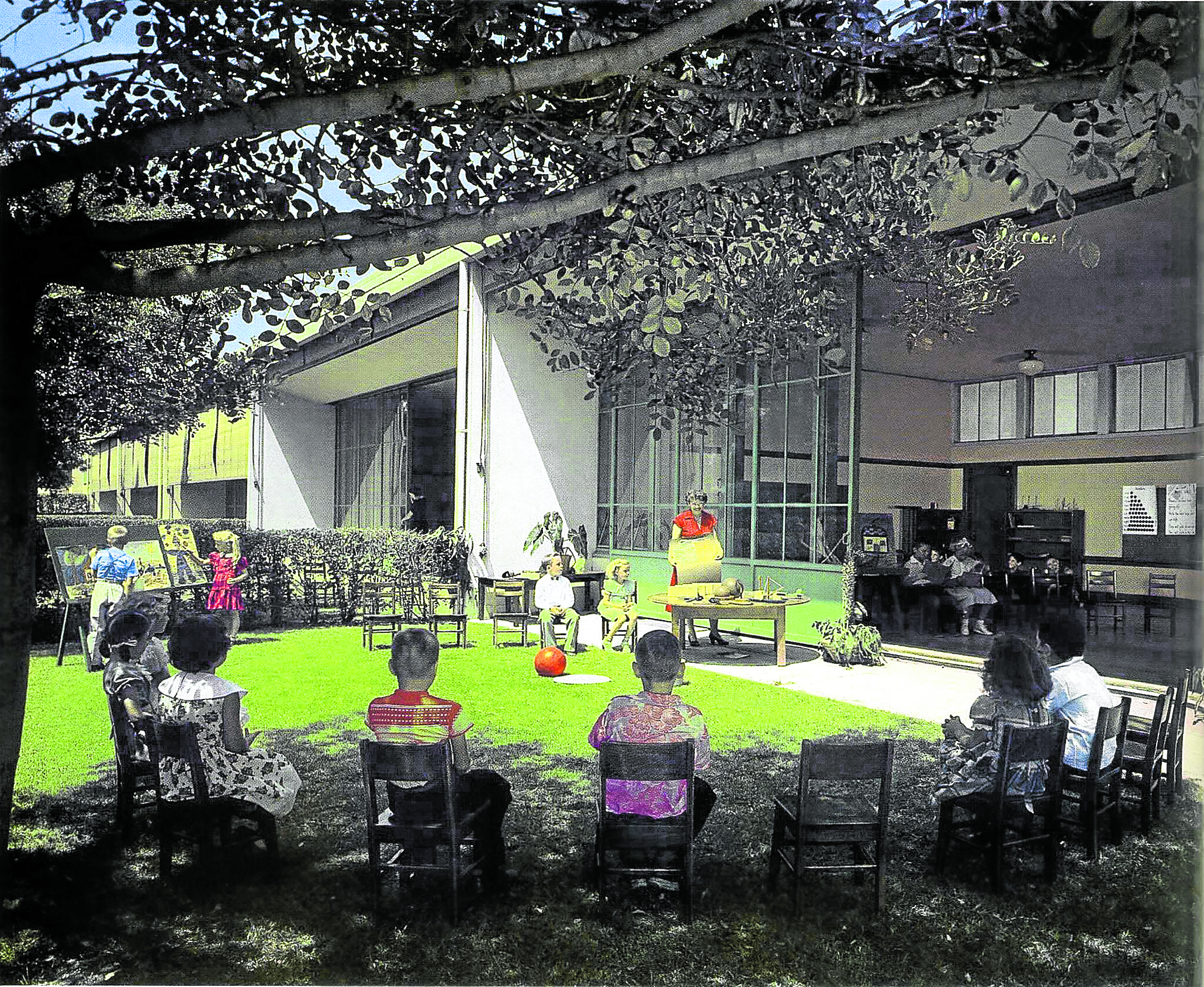

Richard Neutra’s Corona Experimental School introduced natural light and ventilation in children’s educational facilities.

CORONA EXPERIMENTAL SCHOOL

(1935, Los Angeles, California)

This building introduced unique elements to the design of educational facilities, which was aimed at bringing a healthy environment to children cooped up indoors. It was designed by Richard J. Neutra, a prominent architect whose father died of the influenza in 1920. He targeted to bring natural light into the facility when he renovated it. He provided sliding glass walls on the exterior side of classrooms, allowing the students to enjoy the outdoors on a sunny day. These glass walls also provided much sunlight to the facilities. It helped introduce the natural environment to educational facilities, thus turning schools into healthier facilities.

(Sources: drawingmatter.org, calisphere.org, photo via https://en.wikiarquitectura.com)

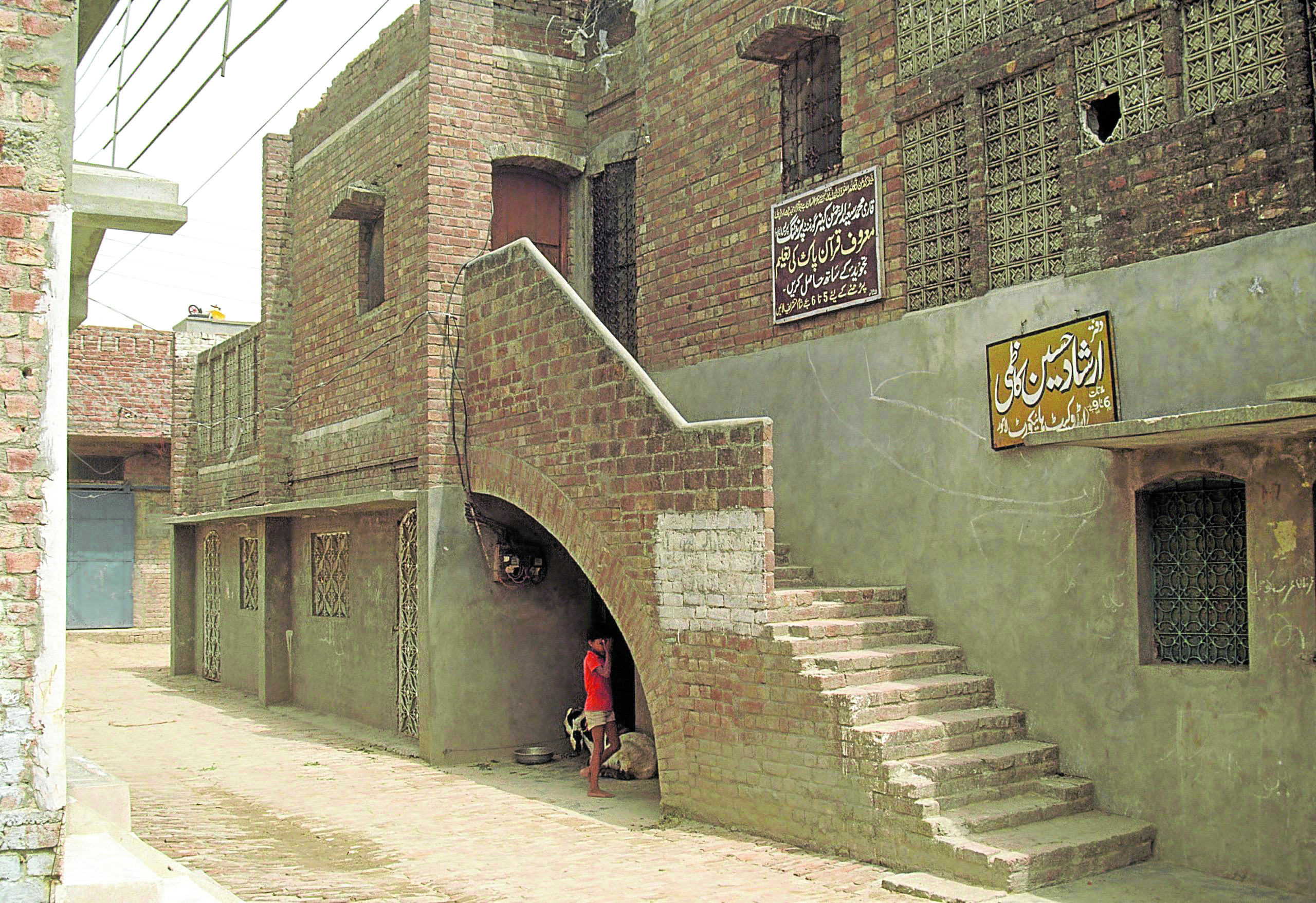

ANGOORI BAGH HOUSEING

(1973, Punjab, Pakistan)

A landmark project of Yasmeen Lari, Pakistan’s first female architect, the Angoori Bagh Housing gave unique focus to women displaced by floods. It was made up of 787 homes arranged in blocks of two- and three-story structures. Pedestrian streets and public plazas connected these homes and ensured accessibility. To accommodate the female residents’ penchant for taking care of domestic animals, Lari provided open air terraces on each level, which could accommodate livestock and produce. These places became informal gathering spaces. The concept of cluster grouping further allowed the homes to be well-protected from harsh summer heat and cold summer nights. Overall, the project has been lauded numerous times for its effective response to the needs of its intended users.

Les Centres GHESKIO

(1981, Port au Prince, Haiti)

Under the leadership of Dr. Jean William Pape, a professor at Weill Cornell Medicine, the group GHESKIO opened the world’s first HIV/AIDS Clinic in Haiti in 1981. It became an international center of excellence researching on the treatment and prevention of AIDS in poor and marginalized nations. Today, the facility trains over 500 health professionals every year to specialize in providing care for HIV/AIDS and tuberculosis patients.

Villa Verde Housing

(2010, Constitución, Chile)

A socialized housing project, the Villa Verde Housing was developed after the devastating 2010 earthquake in Chile. It was designed by Alejandro Aravena of the architectural firm Elemental. Rather than create a poorly made house due to budget constraints and small area, he decided to provide half the structure, thus allocating more funds per square meter. The remaining half of the ground area gave residents the opportunity to expand according to their preferences in the future. The approach was met with positive results over time as people injected their personality and preferences into building the other half of their homes. This project led to Aravena winning the Pritzker Architecture Prize in 2016.

(Sources: www.theguardian.com, Suyin Chia via archdaily.com)

Soma City Home for All

(2011 Soma City, Japan)

Created to serve as community centers in the aftermath of the Tohoku Earthquake of 2011, the Home for All was built to replace 250,000 homes that were destroyed. Funded by donations, the building became a prototype for community buildings around Japan. The project was designed by two firms: Klein Dytham architecture and Toyo Ito & Associates. Representing a large straw hat, the structure serves as an indoor play space for young children. This protected them from possible radiation in the environment brought about by destroyed nuclear plants in the area.

(Sources: www.archdaily.com, Koichi Torimura for the photo)

New York City AIDS Memorial

(2011, New York City, US)

In November 2011, the NYC AIDS board announced an international design competition to create a memorial park. Along with American magazine Architectural Record and industry database group Architzer, the board received about 500 entries from around the world. The winning entry was submitted by the group Studio a+i led by architects Mateo Paica, Lily Lim and Esteban Erlich. Their design was composed of an 18-foot triangular steel canopy, with granite water fountain and benches. Today, the memorial stands as a gateway to the St. Vincent’s Hospital Park in the West Village, and serves as a gathering place to commemorate all the people who fell victim and who worked against AIDS.

(Sources: nycaidsmemorial.org, Studio a+i)

Cardboard Cathedral

(2011, Christchurch, New Zealand)

Two years after the 6.3 magnitude earthquake that hit Christchurch, the Cardboard Cathedral was opened to the public. The eye-catching work was designed by the Japanese architect Shigeru Ban. Cardboard tubes and steel shipping containers were combined to create the Cathedral. The paper tubes were coated with flame retardants and protected by a polycarbonate roof to protect it from harsh weather or heat. Despite its cardboard construction, the building is said to be one of the best earthquake-proof buildings in Christchurch. It has a projected lifespan of 50 years.

(Sources: Bridgit Anderson, archdaily.com)

Amatrice Refectory

(2011, Amatrice, Italy)

This building, which was designed by Stefano Boeri Architetti, was meant to serve as a school refectory in the aftermath of the 2011 earthquake in Italy. Constructed only within 30 days, the Amatrice Refectory was intended to become a multifunctional space for the city’s children. The structure makes use of prefabricated materials. An open public space connects the various rooms onsite, giving the whole complex ample light and ventilation. The whole project consists of approximately 490 sqm. It was one of the immediate architectural solutions to be built for Italy’s population after the devastating earthquake.

(Sources: www.archdaily.com, Francesco Mattuzzi via archdaily.com)

GHESKIO Cholera Treatment Center

(2015, Port au Prince, Haiti)

Cholera became an epidemic in Haiti when in 2010, contaminated waste infiltrated the Artibonite River. In response, the medical community had set up temporary tents to attend to the sick. Unfortunately, the temporary solution was no match for the hot climate of the Haitian sun. To solve this problem, Dr. Jean William Pape of the group GHESKIO had sought to put up a permanent cholera center. The MASS Design Group designed the Cholera Treatment Center to feature abundant access to light and ventilation. More significantly, it introduced an in-house waste treatment system, wherein rainwater is harvested, stored, and treated for use in showers and sinks. The treated water is also used for Oral Rehydration Therapy, one of the procedures that helped dehydrated patients to recover. The center continues to be in operation today, being one of the vanguards of Haiti against cholera.

(Sources: Iwan Baan (photo), massedesignroup.org)

CENTER FOR POSTGRADUATE STUDIES OF CETYS UNIVERSITY

(2016, Mexicali, Mexico)

Designed by the architectural firm Studiohuerta, the Center for Postgraduate Studies in Cetys University featured seismic architecture in an educational setting. Built in the aftermath of a 7.2-magnitude earthquake in the area, the building features thick exterior walls that strengthen the building against ground movement while also protecting it from harsh desert climate. An aluminum screen classing provides a defense against heat gain and encourages natural ventilation. The building combined passive thermal and seismic features to ensure its durability as it stands on the San Andreas fault line. It won the 2017 Architizer A+ Awards for architecture + sustainability.

(Sources: archdaily.com, photo via https://studiohuerta.com/)

UNDERGROUND PARKING KATWIKAAN ZEE

(2016, The Netherlands)

Occupying an area of 15,000 sqm, this underground parking facility was awarded the BNA Best Building of the Year in 2016 by the Royal Institute of Dutch Architects (BNA). The project was designed by the architectural firm Royal HaskoningDHV. Despite its utilitarian purpose, the project is made special by its contextual approach to the building’s exterior. Rather than destroy the natural landscape, the parking facility cleverly blends into the contours of site. This not only allows the structure to respect the area’s topography, it also makes the structure a defensive fort against coastal floods.

(Sources: www.dezeen.com, photo via www.royalhaskoningdhv.com)

TOKYO HAT HOUSE

(2016, Tokyo, Japan)

Built after the 2011 earthquake that shook Japan, this unique house designed by Apollo Architects & Associates offers seismic innovations. Dubbed the “hat house” for its pointy, wooden roof, the structure is enclosed by thick reinforced-concrete walls and a traditional timber roof. Concrete was the material of choice because of its high resistance to ground movement and fire. It has ample access to the sun and ventilation. The house combines traditional Japanese aesthetics with modern materials to create a space that is both cultural and functional.

(Sources: https://www.designboom.com, photo via https://apollo-aa.jp)

THERAPEUTIC GARDENS OF SINGAPORE

(2016-2018, Singapore)

Starting 2016, a series of landscaped gardens were created around Singapore based on theories of therapeutic horticulture. The gardens promised health benefits such as “relief of mental fatigue, reduced stress, and an overall improvement to emotional well-being”. The first garden created in 2016 for the purpose of promoting health was HortPark, which features water elements, wind chimes, and local plants. This was soon followed by the Bishan-Ang Mo Kio Park, Tiong Bahru Park, Telok Blangah Hill Park, and the Choa Chu Kang Park. These gardens became landmark projects in Singapore because they emphasized the importance of interacting with nature to maintain our mental health.

(Source: www.nparks.gov.sg)

AMANI PLACE

(2019, Atlanta, US)

Opened in October 2019, the Amani Place is the first affordable housing project to be certified with Fitwel—a healthy building certification developed by the Center for Active Design. Amani Place features several elements which make it conducive to a fit and active lifestyle. The homes are interconnected with a well-designed pedestrian network, which encourages walking. There’s also an outdoor fitness circuit, a communal kitchen, community garden and community center. Despite its wonderful offerings, the garden community is quite affordable for households below 60 percent of the area’s median income. Overall, the design of the project encourages not only better health for its residents, but also a more beneficial approach to housing and community relations.

(Source: centerforactivedesign.org),

PLAN B GUATEMALA

(2019, Guatemala)

Designed by DEOC Arquitectos in Guatemala City, this project is a disaster relief shelter which was constructed after the destructive Volcan de Fuego eruption in 2018. The shelter is made up of concrete blocks which are hollow and allow the breeze to pass through. A pop of color inside the blocks allowed the families benefiting from the shelter to project their tastes and culture onto the building.

(Sources: www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov, DEOC Arquitecto via www.dezeen.com)

CHINESE TEMPORARY COVID HOSPITALS

(2020, Wuhan, China)

The first country to experience the wrath of the COVID-19 virus, China pioneered the use of architecture to fight the ongoing pandemic. In 16 days, 16 hospitals were built to receive COVID-19 patients. Although transient facilities, the hospitals were fully equipped. CT Scanners, mobile P3 laboratories, and even a medical waste incinerator were present to ensure that all people and materials in the facility were properly handled. A specialized sewage treatment system was also installed in these temporary facilities to ensure that the virus would be contained. In a little over a month, China was able to control the rapid spread of the virus. On March 10, the temporary hospitals were closed.

(Sources: www.xinhuanet.com, Painjet via Wikimedia Commons)

JAVITS CONVENTION CENTER

(New York, US)

This existing convention center in New York City was temporarily transformed into a military medical hospital during the worst of the COVID-19 virus pandemic early this year. The Center accommodated 68 beds, crucial medical equipment, and military staff in its short operation. It effectively served as a field hospital where tent cubicles had been set up to take care and treat COVID-19 positive patients. The hospital was eventually dismantled in May when the cases began to reduce in number, but the equipment remains in case of a sudden resurgence.

(Sources: www.vox.com, Ajay Suresh via Wikimedia Commons)

STRAWBERRY HILL BEHAVIORAL HEALTH HOSPITAL

(2020, Kansas, US)

Newly opened when the COVID-19 pandemic began, the Strawberry Hill Behavioral Health Hospital was not designed to face any epidemic. It was originally an office building repurposed into a medical facility. Yet the building’s features provided a significant element that made the center an effective facility in handling the virus: flexibility. The hospital’s treatment center was divisible into smaller pods that allowed areas to be isolated or joined together. This helped the staff treat patients suffering from the COVID-19 virus without having to worry about infecting other people in the building. It also helped with staff anxiety of moving between areas that held COVID-19 positive cases.

(Source: www.cannondesign.com)