An ongoing masterplanning project with a Japanese client allowed us to reexamine traditional design principles. We often admire the subtleties of Japanese aesthetic, the intricateness amid simplicity, the representation of complex ideas in profound symbolism, and the deliberateness of form and movement.

These ancient ideals are manifested in words for which there are no direct translations.

Untranslatable vernacular terms reveal a trait of culture unique and understandable to its people but difficult to articulate or transcribe to the non-native. It is not unlike our Filipino design ideal of “maaliwalas” or our value of “malasakit”—translations are insufficient and are approximations, at best.

Traditional Japanese approach to design manifests in various techniques and approaches in art and architecture. It reflects a deep and complex set of values that transcends aesthetics and reflect sa way of life that speaks of resilience, simplicity, value—ideals that remain profoundly relevant today.

Kintsugi

More an art form than aesthetic philosophy, kintsugi is derived from Japanese words “kin,” which means golden, and “tsugi,” which means repair. It is a traditional technique that uses precious metals such as gold or silver to bring together pieces of a broken pottery by lining the cracks, giving it new life, keeping it useful and adding value to the broken object. Many kintsugi pottery are treasured artwork. The technique suggests many things. A broken object can be repaired into something more valuable. This speaks of resilience and transformation.

Shokunin

The approximate translation of shokunin is craftsman or artisan. These however do not fully capture the spirit behind the Japanese term, which transcends technical competency and encompasses the social obligation to give one’s best to serve the general welfare of the people. It is the relentless pursuit of perfection in one’s craft or vocation. It is both work ethic and the journey towards excellence and higher purpose.

Kanso

Simplicity or elimination of clutter. This refers to creating the simple and natural through the omission of decoration and the non-essential. It refers to a level of clarity and directness, devoid of the superfluous elements that do not serve the object’s purpose. Kanso reflects the belief that for an object or space to be beautiful, adornment is not necessary.

Shibui

Beautiful by being understated, subtle and unobtrusive. Objects that possess these traits may appear simple overall but will reveal a level of intricateness and fineness of detail, material and craftsmanship when viewed up close. It is a subdued form of expression that aims to balance simplicity and complexity, the articulate with the elegant.

Wabi Sabi

The “Melancholic Beauty.” This is the Japanese aesthetic ideal that appreciates the fleeting, the incomplete, the imperfect. It is about celebrating the now, as things are, rather than as how they should be. This is also the root philosophy behind kintsugi. It is not about celebrating poor craftsmanship, but it is about accepting imperfection as part of what makes something beautiful—the patina in an aged cup, the uneven texture of a claypot, the impermanence of all things that force us to be mindful of the here and now.

Ma

The void—it literally means a gap, a space or a pause. It refers to the importance of empty space having equal value to the object that is being depicted in the artwork. We sometimes refer to this as negative space. In architecture, these are the spaces that are formed by enclosing walls, or the space that envelops buildings. Ma is the space that allows freedom. It is also what graphic designer, Alan Fletcher, referred to when he wrote “space is substance.” Ma is associated temporally as a pause. In space, ma is what gives shape to the whole. In time, it is the interval that allows growth.

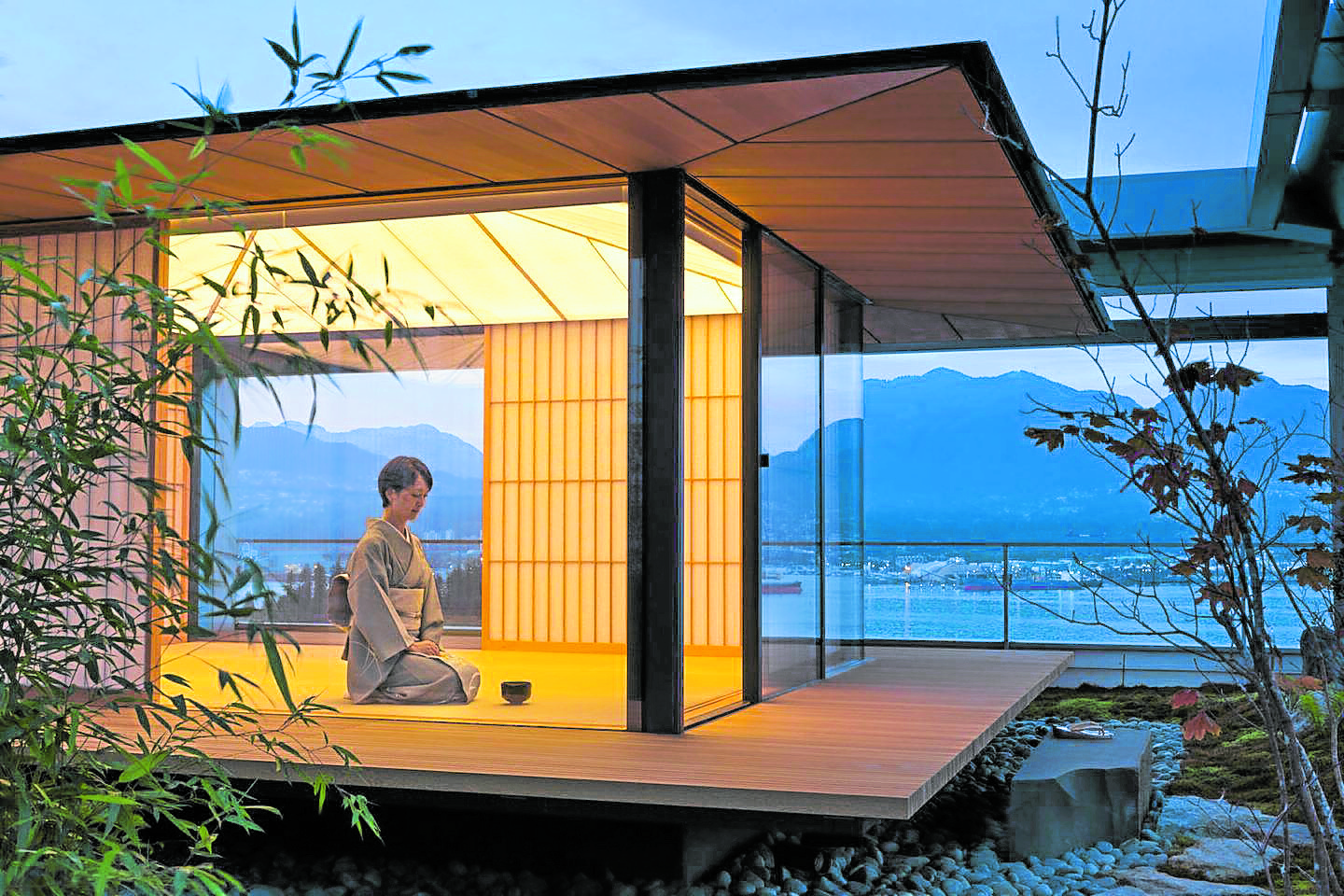

The architecture of the ephemeral, Shigeru Ban’s paper pavilion —SHIGERU BAN ARCHITECTS/ HIROYUKI HIRAI

The Ideals Applied to Today

What if we deliberately design modern spaces to be appreciated up close rather than from afar? Or at the slow pace of the human gait, rather from a speeding car? Or repair older sections of our cities rather than create new, sprawling developments in greenfield sites? What if we create temporary places to suit changing needs—allowing places to evolve, therefore forever incomplete and in a state of becoming? What if we start to value the voids and open spaces as much as the objects and buildings placed around them?

These ancient ideals can be applied at any scale—from the design of a small object to the planning of large cities. They are about favoring the simple over the complicated, the subtle over the grandiose. Applied to the present and the practical, the ideals are about pursuing purposeful and meaningful simplicity, recognizing that the societal cost of complexity can be enormous.

William of Ockham, a Franciscan friar, once said that “plurality should not be posited without necessity.”

His was a call for simplicity, which is now known as Ockham’s Razor. The relentless pursuit of the excellent and the simple while capturing the richness and essence of the complex is the ageless epitome of good planning and design.