Dolomite is a material that has been around for ages, but it was only recently that it sparked the interest of many Filipinos.

Earlier this month, the Department of Environment and Natural Resources (DENR) pushed through with its plan of covering a 500-meter stretch of Manila Bay’s shoreline with dolomite sand—a move that drew both praise and criticism.

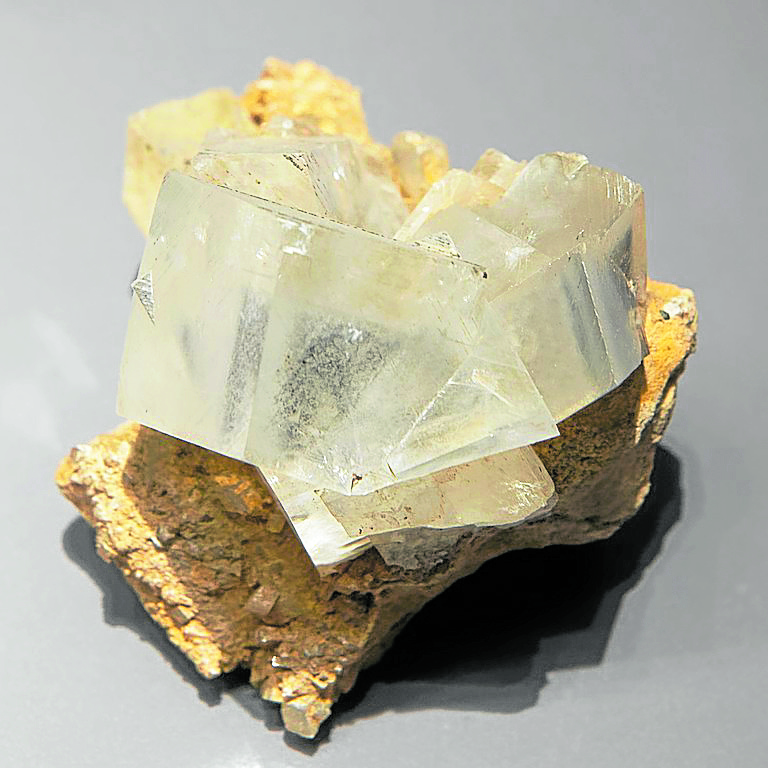

Unbeknown to many, dolomite is actually all around us. It is frequently used in the production of concrete, exterior cladding, roads and garden paths. While its use as artificial beach sand in Manila Bay raised some eyebrows, this is not the first time that dolomite was used for this purpose. Manmade beaches in France and Singapore have also been built with the same material. In addition, many heritage buildings in Italy, Germany and the United Kingdom were also made out of dolomite limestone, some of which still stand today.

If you’re one of those curious about the controversial material and would like to know more about its effects on the environment, history would be a good place to look at some examples. Read on to discover existing dolomite sites around the world, and determine for yourself if the Manila Bay project would prove to be a wise move in the long run.

Heritage structures prove dolomite’s durability

As far back as the 16th century, dolomite was already used as a construction material in Europe. Italian writer Francesco Milizia even wrote instructions in 1781 on how to choose and identify dolomite limestone suitable for building. At that time, concrete, as we know it today, has not been developed yet. Rock, limestone and other naturally occurring minerals were the materials of choice for construction.

Dolomitic limestone was preferred by many builders of the past not only for its abundant supply and easy availability, but also because of the material’s durability. In Italy, Spain, France, Germany and England, dolomitic structures built from the 16th to the 17th centuries still survive.

According to Rita Vecchiattini, a scholar from the Università degli Studi di Genova in Italy, “archive documents and empirical datum that dolomitic limestone-based mortars do very well in the test of time” made the material the primary choice of many ancient builders. While the method of constructing and mixing mortar has varied over the years, dolomite remained a primary building material for ancient buildings.

Today, ancient dolomitic structures in the world still stand, attesting to the material’s innate strength. One famous example of this is the Saints Peter and Paul Church in Krakow, Poland. Its façade is made of dolomite and features the Baroque style of building. In Jerusalem, dolomitic limestone makes up the face of every building in the city by law. The material has become commonly known as “Jerusalem stone” as it has been used in many of the region’s most iconic structures, including the Wailing Wall in the Old City. These structures show that dolomite is capable of withstanding the test of time.

Manila Bay isn’t the first beach to feature dolomite

Located in the northwestern Mediterranean, the French Riviera is a popular tourist spot that is made up of both natural and artificial shorelines. While the space in the original site is quite limited, population boom and tourist demand in the late 20th century led to the development of man-made beaches.

Today the French Riviera is made up of 21.5 percent artificial shorelines serving as tourist beaches, yachting harbors and reclamation fill. These shorelines were created out of fine sand or gravel quarried from limestone, sandstone and dolomite. They not only added space to the French Riviera, but they were also used to upgrade existing natural beaches to make them more attractive to tourists.

According to an article written by the French scholar E.J. Anthony for the Journal of Coastal Research in 1994, the artificial beaches had both pros and cons. On the upside, they did succeed in extending the existing beach length to cater to the rising number of residents and tourists in the area. These man-made shorelines, however, require regular maintenance, which include protective measures and “renourishment” of the shore. These procedures incur high expenses, which have led some to view them as an unnecessary indulgence. The rise of tourism in the area has also led to the increase of water pollution especially during the summer tourist season.

Nevertheless, Anthony states that “artificial beaches have compensated for less than 1 percent of net loss of natural beaches.” Majority of this loss can be attributed to the reclassification of rocky shorelines, as these were upgraded to accommodate yachts and beachgoers. He also states that the “creation of these artificial beaches has allowed for enhancement of the recreational quality of the transformed natural shore.”

The Larvotto Beach in Monaco is one of the manmade dolomite beaches that compose the French Riviera.

Dolomite construction reveal effects on human health

Those who are specifically interested in the effect of dolomite on human health would probably take a look at the use of dolomite in the construction industry for answers. While the material is generally classified as non-toxic, several studies have revealed that some respiratory disorders are associated with exposure to high amounts of dolomite dust.

A study published in the Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal in 2012 showed that “symptoms such as regular cough, phlegm, wheezing, productive cough and shortness of breath were significantly more prevalent among exposed workers” using dolomite in a dam project. The same study, however, stated that “no significant abnormalities were observed in the chest radiographs of both exposed and non-exposed individuals.” These findings suggest that while minor respiratory problems can be caused by dolomite dust, the study could not prove that prolonged exposure to the materials would cause significant illnesses in the long run.

Overall, Manila Bay would probably continue to remain controversial as long as it features dolomite on the beach. Love it or hate it, dolomite is everywhere. More likely than not, you probably have encountered the material before without even realizing it. Only time can tell whether this aggregate would be a benefit or nuisance to Manila. For now, however, it’s here to stay.

References:

“Natural and Artificial Shores of the French Riviera: An Analysis of their Interrelationship” by E.J. Anthony (Journal of Coastal Research, Winter 1994); “Respiratory disorders associated with heavy inhalation exposure to dolomite dust” by M. Neghab et.al (Iran Red Crescent Medical Journal, Sept. 2012); “The use of dolomitic lime in historical buildings: History, technology and science” by Rita Vecchiattini (Proceedings of the First International Congress on Construction History, Jan. 2003); Jakub Halun, Yourway-to-Israel; Marie-Lan Taÿ Pamart and V&A Dudush – Panoramio via Wikimedia Commons