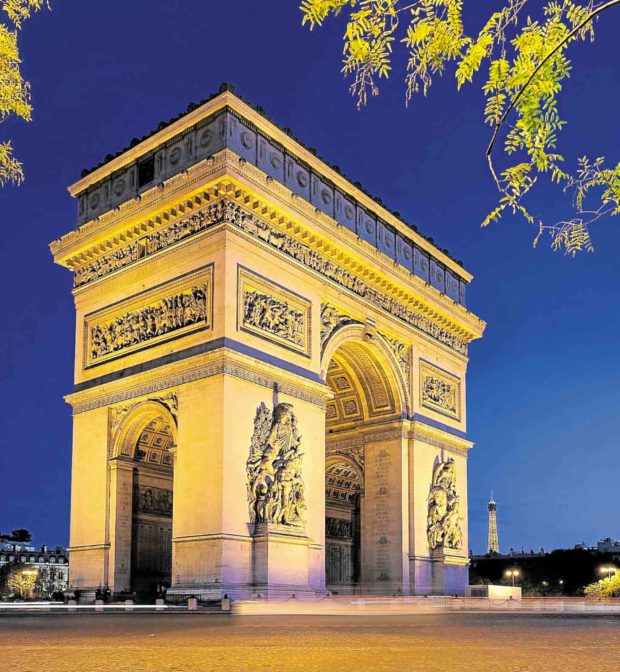

Arc de Triomphe, Paris—One of the iconic landmarks in Paris, France with its eternal flame sheltered by the archway

Monuments and memorials have been essential elements of the urban landscape. According to the “Image of the City” by Kevin Lynch, monuments and memorials are part of landmarks and are points of interest in a city. These do not define the city per se, but rather act as markers meant to narrate that something had happened, or someone significant had been there.

A monument is a type of structure created to commemorate a person or an important event, while a memorial is an object established to remind one of a person or event. While both pieces differ in intended function, both share the same importance on the social and cultural aspect of a place, city, or on a wider perspective, a nation.

A vessel of stories

Monuments and memorials are stories of the past, moments in time frozen in bronze, stone, granite, marble or even glass.

It is a simplified narrative; a physical representation of an event which happened in the past. It has a clear and distinct function—by placing a physical reminder in the public space, it enhances the recollection and integration of memories related to the subject of the commemoration and its narrative. It has the power to tell a story through its etched inscriptions, sculpted human forms and intricately designed ornamentations.

These landmark pieces are made not to transport us back in time, but to constantly remind us of the history that was.

For instance, there is the Arc de Triomphe in Paris, a vivid monument which survived various regimes. Due to its popularity, it has become successful in imparting the history of the city, while at the same time engaging people through it.

Monument and memorial architecture

Monuments and memorials are slabs of stones of heroism or tragedy. Through their architecture, these iconic landmarks have been able to convey not only a narrative. They are also able to affect people’s feelings and emotions. Listed here are three iconic monuments and memorials around the world.

Vietnam Veterans Memorial (Washington DC, US)

A wide V-shaped block of polished black granite wall sunken into the ground with etched name inscriptions of nearly 58,000 American servicemen listed in chronological order of their loss was the winning design for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in 1981.

This concept bested 1,400 others and was submitted by a 21-year-old senior architecture student at the Yale University, Maya Lin. The mirror-like surface reflects the images of the surrounding trees, lawns and monuments.

The memorial’s wall points to the Washington monument and Lincoln memorial, thus bringing this memorial into the historical context of the country.

The memorial proved to be a pilgrimage site for those who served in the war and those whose loved ones fought in Vietnam. Eventually, it became a sacred place for healing and reverence.

Its horizontality suggests serenity. Its sober massiveness and approach bring about a strong emotional sentiment. The tactile factor of the engraved names of the American servicemen just adds to the overall experience one feels upon visiting the site. It was not just a controversial block of stone—it was an emotional immersion on its own.

The 9-11 memorial as a large void depicting reflecting absence as designed by architect Michael Arad

9/11 Memorial (New York, US)

Arch. Michael Arad’s design features twin waterfall pools surrounded by bronze parapets that listed the names of the victims of the 9/11 attacks and the 1993 World Trade Center bombing. Entitled “Reflecting Absence,” each of the pool descends 30 feet into a square basin. From there, the water in each pool drops another 20 feet and disappears into a smaller central void. Although water flows into the voids, they can never be filled. It is thus a representation of the designer’s concept: absence made visible.

Unlike the other monumental landmarks, this place of reflection and memorial highlights no mass, volume, or form—it is actually a void in space. It is by using this negative space that the designer begins to appeal to the emotions of the people. With the clever use of the sound of the cascading water, the place offers tranquility and contemplation amid the bustling noises of the city.

People power monument—The nationalistic masterpiece of Eduardo Castrillo which represents how the whole country felt during the 1986 EDSA revolution

Edsa People Power Monument

“A monument representing how the artist and how the whole country felt during the 1986 Edsa revolution.” This was how Ovvia Castrillo, daughter of the late renowned Filipino sculptor Eduardo Castrillo would describe the People Power Monument.

The pyramidally-composed monument is set atop an elevated position. Composed of three tiers, the first tier has chained men and women with arms linked together. The middle tier represents various people who had joined the protest: a musician, a mother carrying an infant, priests and nuns. The top tier is a towering female figure whose arms are raised towards the sky. She has unchained shackles on her wrist. The back is a staff and the flag.

The monument depicts the power of lines and forms to convey activism and nationalism. The vertical stance of human figures signifies strength and solidity yet the diagonally-raised arms convey a fight and dynamism to achieve freedom.

The whole of the composition is active. Its grandeur volume speaks amass. The narrative is diverse but united. Indeed, the monument tells a story of a fight for freedom, truth and justice. The monument serves as an everyday reminder that citizens are more powerful than their leaders and that the fight for the good is worth fighting for.

Memories shaping society

Through the initiatives and movements of various heritage conservation groups, more monuments and memorials are being restored. These are considered a significant part of the urban landscape not because they serve as iconic landmarks or urban ornaments, but they also help us associate the future to our past.

They are narratives of our history—a physical channel through which people can connect to their cultural identity. They unconsciously make people reflect and realize.

In a way, it is a tool that can help in shaping society. It is a constant reminder of our past and significant learnings from our history. From that, we shall progress as a better individual and a better nation.

The most effective monument punches through the heart. It is more than a standing glory of stone or metal of heroism. It is that emotional experience one has gone through while enjoying this public installation of history. It carries with it memories, stories, and most importantly, cultural identity.

Sources:

911memorial.org

biography.com

manilatimes.net

vvmf.org

commons.wikimedia.org

Wikipedia.org