NOSTALGIA SUNDAY People continue to ask for the chocolate that defined their childhood. —PHOTOS FROM RANDY ONG

The ditty goes: “Darating na, darating na, si Mama at si Papa. Sana maalala, lambing natin sa kanila. Isang balot ng ‘I love you,’ isang balot ng Serg’s.”

This ‘90s jingle speaks to this day of how Filipinos—perhaps from the boomers to the old millennials—miss their sari-sari store-accessible chocolate brand.

Christy, now in her 40s, remembers: “Among the chocolates when I was growing up, Serg’s was at the top. I would savor every minute from peeling the wrapper off followed by the crinkly silver foil to breaking off a piece of the chocolate and letting it melt in my mouth.”

Mikey, also now in his 40s, would always set aside a part of his allowance just so he could get his daily treat. While cheap, the taste was tops, he says. “The love I had for Voltes-V, it’s the same I had for Serg’s.”

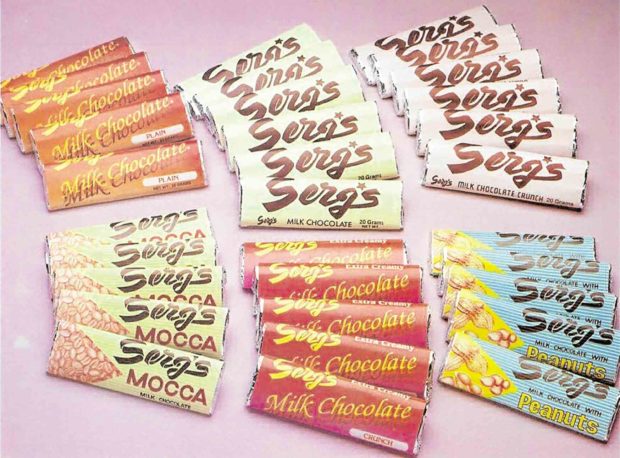

The pinstripes wrapper had become so ubiquitous beside chocnut and sugarcoated candy balls, but unlike its cavity-inducing peers, it suddenly vanished and left a hollow in the hearts of hyperactive children.

Many articles from the internet provide stories of what happened to Serg’s, but major details which have not been revealed—up until now—show the brand’s tenacity, of wanting to come back again and again despite going through a series of unfortunate events.

Goquiolay family

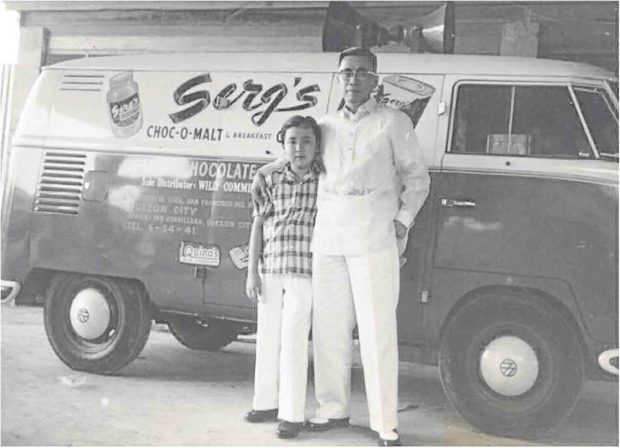

Businessman Antonio Goquiolay formed Serg’s Products Inc. in 1954 in response to expensive, albeit easily melting foreign brands such as Hershey’s. Armed with techniques and trends from abroad, he tried to make chocolates in his own kitchen, mixing and matching ingredients that would suit the climate of tropical Philippines.

The market readily welcomed the product, later on allowing the startup to put up a factory in their own home in Quezon City in preparation for a widescale operation.

In an interview with Philnabank News in 1982, Goquiolay’s son Sergio—after whom the brand was named—said: “There were two things that worked in Serg’s’ favor at that time. First we had no [local] competitor. We were the pioneer in the business so it was easy to grow. Second, we always emphasized quality and although we sold our products at a low price, we never sacrificed quality.”

But while the popularity of the brand skyrocketed, things have not been smooth for the Goquiolays. Discrimination against those with Chinese descent plus the kidnappings and security threats during the 1960s forced the family to migrate to the United States.

From there, Antonio continued to operate the company by fax and telephone until the 1970s with the help of a stepdaughter who remained in the Philippines.

This extraordinary feat, however, meant the company would be on the radar of the government. According to the family, the Goquiolays’ alleged close relationship with the Marcos family led to its downfall in 1986.

“But it was all a misunderstanding. But after the Marcoses’ rule, they just confiscated and confiscated and confiscated [different companies],” a source says. The asset privatization arm of the Aquino administration took over the company, and Serg’s chocolates, for the first time, went missing from the shelves.

Sergio returns

In the aftermath of the fall of the dictatorship, the family decided to lead a quiet life in the United States. Sergio later earned a PhD in marketing then went on to become a professor at a university in Michigan.

But with legacy foremost in his mind, Sergio sold his assets in the United States to back his bid to return to the Philippines and reclaim his family’s business—and reputation.

By the 1990s, the second-generation chocolate peddler made the company so big it had 5,000 employees manning the assembly lines and the distribution networks.

The company bought two new manufacturing hubs, one of which was in Cainta, Rizal, that had its own cocoa grinding facility. Serg’s also began to export its products to other Asian countries while its cacao butter made its way to Japan, Hong Kong and the United States.

But to support its massive expansion, Serg’s had to take out loans in dollars.

Then the Asian financial crisis stopped it in its tracks. By 2001, Serg’s entered the dreaded bankruptcy.

Son-in-law

In an interview with the Inquirer, Sergio’s son-in-law, Randy Ong, says that despite the financial difficulties of Serg’s in the years before it entered restructuring, the patriarch never buckled in making things work for the company.

A visionary, Sergio took in Ong as a consultant to manage the firm’s IT operations, a big step at that time for any company that wanted to secure a spot in the globalized community.

He says the family was so unassuming that he did not even know he was dealing then with Goquiolay’s daughter, Nadine, whom he would later marry.

But fate would leave its mark on the company anew. Months after the company filed for a bankruptcy, Sergio died from a massive heart attack while playing badminton.

Production stopped and the family had to sell assets to pay off creditors and support its remaining workers. It did not help that its facility in Cainta caught fire due to an old wiring, damaging some equipment and killing the company’s lucky arowana Sirikit.

Little did the company know that more trouble was coming.

Looting

Tired and heartbroken, the family went back to the United States to get a much needed break. There, the family tried to pool as much as they can to pay off creditors. Sergio’s widow, Nualsri aka Yeng, even planned on selling the house in the United States.

“My mother-in-law said, ‘Your dad would want this company to survive. He devoted his life, his family for this company, we must continue. We get the money from somewhere else, and in the meantime, the [Securities and Exchange Commission] could help freeze the creditors. We continue to operate, we keep things lean,” Ong recalls.

After the temporary break, the family returned to the Philippines … but to machines not working, with parts cannibalized and missing. Perhaps afraid they would not get a good bargain in the company’s restructuring, some union members tried to take matters into their own hands and took whatever they can—from bronze wires to whatever can still be sold outside, Ong says.

Even with the company’s legal troubles piling up, the family in the end decided not to pursue the same route against the employees.

Day in and day out, the Goquiolays would exhaust their energies crying. “Let’s just have the company die for itself, by itself, a natural death.”

Finally, and perhaps permanently, they set off for the United States.

Machine scraps

But the IT guy had other plans. Perhaps his father-in-law’s perseverance rubbing off on him, Ong knew the story did not have to end there.

In the United States working as an IT consultant for big firms such as Ford, Ong would still get queries, “When will you make Serg’s again?”

Serg’s elves working on the main chocolate line at the new, lean choco factory in the Goguiolays’ ancestral home in QC

“Even those who have not tasted the chocolate before, they would ask me. One approached me and said if not for Serg’s, their family won’t be here … because her lolo bought Serg’s bars to woo her lola.”

It hit him. He had to revive the company again. He kept a Facebook page where he, one post at a time, fed on nostalgia and people’s penchant for comebacks and revivals.

He would come back once in a while to the Philippines, testing the waters and rebuilding Serg’s original base—the Goquiolay’s ancestral home—in Cordillera in Quezon City.

It wasn’t easy, of course. What remained of the rich history of Serg’s was also lost during tropical storm Ondoy’s (Ketsana) onslaught in 2009—photos, clippings, memorabilia were gone.

But Ong was adamant. No fire or flood could kill the family legacy, he says—one of his two kids is named Sergio after all.

Moulds

His mother-in-law says he’s crazy and that’s just how he describes himself.

Crazy enough to sort out the legal obstacles and then go to the Intellectual Property Office to have Serg’s trademark registered. He also went to different locations abroad, looking for equipment that he could use to complete his own “little commissary, bit factory.”

In one of his excursions, he managed to track down old Serg’s equipment. One of those who managed to get hold of the old company machines when they went into auction was KSK Food Products, the maker of Boy Bawang.

They had in their possession the old moulds for the Serg’s chocolates, which the company gave to him without asking for anything in return. “I had goosebumps,” Ong says.

Wisdom or folly?

Ong gave up his job in the United Sates. Using only his savings and a little fund from the family, he intends to start manufacturing chocolates again—using the old Serg’s recipe.

His wife had given him her blessing.

His little chocolate factory in the old ancestral home is almost complete, and little by little, he has been getting help from his elves—the workers. He says he would be keeping the operations lean in the meantime, also relying on the gig economy for distribution and marketing.

He says he is open to investments in order to jump-start Serg’s once again. He can’t say for sure when he can finally roll out production, perhaps a whisper of a start early next year.

Asked if he’s not scared of the fact that many chocolate variants are already out in the market, he says: “There will always be a market for anybody, anything, any product. Even if, say, one will not buy flip-flops from a Binondo stall because of the flower design, one will always find them attractive. It’s the same thing with Serg’s. There are people who are very nostalgic, very patriotic for local brands.”

He admits the venture could turn out a folly, but he’s willing to take the risk. He remembers his father-in-law describing him as a resourceful person.

Is he ready for failure? Ong says: “You won’t have any success unless you have failure in the sense that you will not be able to learn anything. Just look back at the history of this company.”

Perhaps Serg’s old earworm will come true one day—parating na, parating na—Ong wants the Filipino icon gracing shelves once again.

For updates and questions about the product, contact: info@sergs.com, or visit www.facebook.com/sergsbrands/