The economics of hand-weaving

Their origins were traced back to the Iron Age when the knowledge from different parts of the region were exchanged through the trade routes that ran through both land and sea.

Basketry and weaving were both traditionally created for religious or ritualistic, and functional needs. The commonality in their origins can be seen in their symbols, motifs and imageries.

As farming and agriculture became more popular, the art of weaving held ground as a home-based livelihood for women. As the men went off to farm, the women stayed home, took care of the household and children, and squeezed in time to weave every basket and textile they needed.

In the Philippines, there has been a resurgence of interest in hand-loomed or hand-woven fabrics. It is visible most especially in the fashion industry, but just as present in the elements of interior design through items such as blankets, pillow covers, hand towels, table napkins, runners and other houseware. The collective initiative to increase demand for local handcrafted material is motivated by the cultural need to preserve the craft—a tradition taught to the next generation—and to support the economic needs of women in far-flung rural areas who engage in these crafts as their livelihood.

But nowhere in Southeast Asia is this craft of fabric-weaving most prolific than in the nation of Laos. Here, methods and patterns have been handed down through the generations, with the variety in design demonstrating the diversity of the ethnic groups and their corresponding regional styles.

Hand-loomed weaving is so much a part of their culture that the Laotian women have been known to prove their worthiness as wives and mothers by demonstrating their skill and ability through the quality of the fabrics they produce.

I was fortunate to have had the opportunity of visiting a few weaving villages in the Philippines, but I had the thrill of experiencing this difficult, little appreciated craft when I visited the town of Luang Prabang in Laos.

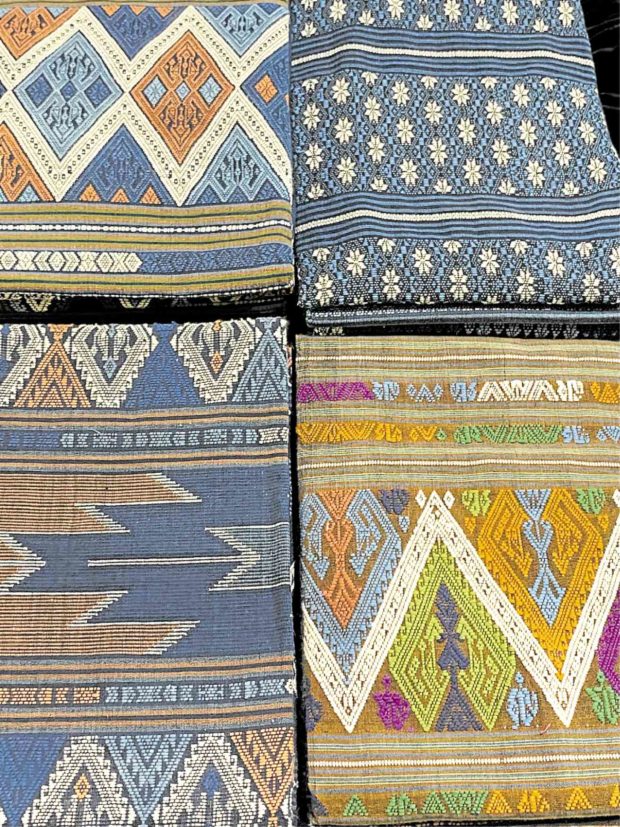

Through its streets and markets, one gets to understand how prolific the craft is, and the aspect of skill is made even more evident after seeing drape after drape of textile in some of the finest material quality and design.

In Laos, the motifs are mainly from the snakes and dragons of their Buddhist beliefs, integrated into patterns of diamonds, triangles and zigzags. Fortunately, their land supports the growth of cotton and mulberry trees, making both silk and cotton the threads of choice for their textiles.

To immerse myself in this love and curiosity for the hand-loomed, I visited the “living crafts” center of Ock Pop Tock (translates as “East meets West”), the artisanal social enterprise for loom weaving that was founded in year 2000 by two women, one Laotian and the other English, who are considered pioneers of social business and ethical textile in the region.

Ock Pop Tock is a venue that raises awareness on the cultural and artistic value of hand-loomed textiles, thereby elevating the economic value of the craft.

I enrolled in their three-hour weaving class where I would learn to make my own small piece of fabric. After a short briefing and upon choosing my preferred design pattern and colors of yarn, a young woman named Ti taught me how to unravel and spool silk using a spinning device.

Once I had my little spools of silk yarn, I was led to a loom, that ingenious wooden frame that holds threads (called the warp) in an already pre-assembled arrangement into which I would run my spooled yarns perpendicularly through by way of a “shuttle,” again and again. Slowly, I would build up my fabric. In between running the shuttle, I’d have to activate bamboo foot pedals to open up the threads to accommodate the shuttle, then beat the thread in to tighten the weave.

It sounds simple, but it is rhythmic hard work that demands attention.

What I did not experience was this entire production chain, which starts from harvesting the fibers, spinning them into yarns, dyeing the yarns into preferred colors, and finishing the fabric pieces with knotted tassel or edgings.

More than learning how to weave, the bigger takeaway of this experience was gaining a clear insight on the process and understanding the effort required to enable this craft. I also understand now why hand-loomed textiles cost a lot of money.

The revitalization of hand-weaving not only supports the women in the rural areas, but ensures the survival of this heritage craft as well.

As it is improved, improvised and developed to cater to the current market needs, I am hoping that in lieu of imported machine-woven textile, more hand-loomed fabric can be used in larger scale applications such as hotels and other commercial establishments. This will not only be of economic benefit to the rural women but it will also expose this craft to a larger audience for the greater appreciation of its heritage value.