On July 8, at the SL Agritech-GoNegosyo launch of the Masaganang Ani 300 to reward farmers who will harvest 300 sacks (15 tons) of palay per hectare, a leader asked for justice for rice farmers.

While those who can attain the 15-ton production target should be rewarded, this cannot be immediately attained by more than 95 percent of our rice farmers. Because of our inadequate agriculture support services and our low hybrid rice usage, we are not yet producing the minimum 4-ton-per-hectare yield necessary to survive the rice tariffication law.

The Philippine government was given 22 years by the World Trade Organization (WTO) to prepare them for today’s 35-percent rice tariff. But our government did not give them the support measures other governments gave their farmers. It is unfair that our farmers will now be left to fend for themselves. Ironically, it is the traders, not the consumers, who are benefiting most from this law.

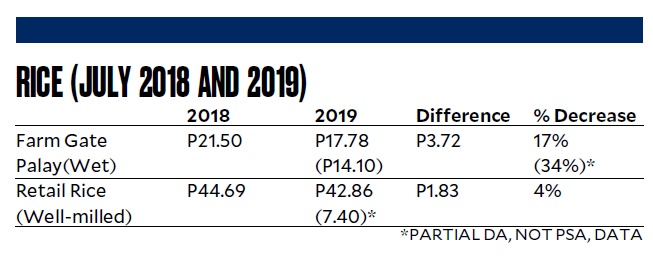

Consider the Philippine Statistics Authority report below taken on the first week of July.

PSA data showed that farm gate price has dropped by 17 percent. But the drop in retail price was only 4 percent. Assuming the 2.1 multiple of farm-gate to retail price in 2018, the retail price in 2019 should be P37.34, not P40.86. Instead of the consumer getting the P7.35 decrease in prices, it is the trader that gets all of it.

In other reports, the retail price decrease in many areas is only P1 (not P1.83), while the droph in the farm-gate price in all 11 areas where DA collected data averaged P14.10 (not P17.78). The DA data showed the following: Baguio City-P13.00, La Union-P14.50, Pampanga-P9.00, Cavite-P13.00, Oriental Mindoro-P14.50, Albay-P14.50, IloIlo-P17.50, Leyte-P12.00, Zamboanga del Norte-P16.50, Zamboanga Sibugay-P15.50, Butuan City-P15.00. If these are accurate, then the retail price was down by only 2 percent, while farm-gate price declined by 34 percent. This means the average farmer will get only P15,840 a hectare, which is way below a decent survival rate.

But all is not lost. Safeguards can still be implemented.

Here is the official statement: “A WTO member may take a safeguard action to protect a specific domestic industry from an increased import of any product which is causing serious injury to the industry.” WTO allows us to take safeguard measures, which effectively means temporarily increasing the tariff. Tariffication is good, but we had to implement the very low 35 percent because of a previous WTO commitment.

Unfortunately, this adjustment is usually done only after two years from the start of the injury. We should try to shorten this period.

Another measure we should use is to provide much-needed subsidies to our farmers. WTO allows de minimis support up to 10 percent of the commodity’s value of production for developing countries. This amounts to P39 billion. We should use this option.

Every P1 palay price decrease means P17-billion loss for the farmers. Thus, the P3.73 per kilo decline reported by the PSA (though possibly understated) means P63.2 billion lost by the farmers this year. This loss is much more than the P10 billion support provided by the Rice Competitive Enhancement Fund (RCEF).

Unfortunately, none of the RCEF has been allocated for inputs such as fertilizers and hybrid rice seeds. The supplemental budget subsidy should thereforeenhance the RCEF by providing these inputs. If this is not done, the RCEF must be reconfigured for these inputs to replace some of the current measures, thusreprogamming part of the less urgent P5-B mechanization for later use.

We must embark on a public-private partnership with emphasis on farmer involvement. This was not sufficiently done. This way, we can formulate the necessary measures for our farmers to improve their profitability, compete effectively with rice imports, and most importantly, get the justice they deserve during this time of their great crisis.