Religiosity of Japanese aesthetics

You rarely hear religion and beauty together in a conversation. Yet, when it comes to Japanese architecture, one cannot seem to exist without the other.

The Japanese way of building takes into consideration the people’s beliefs. Shintoism and Buddhism, Japan’s major religions, are both reflected in their built forms. The first one sees soul in things, while the second seeks a state of enlightenment. The principles of both religions manifest themselves in the works of the Japanese. These expressions are what makes the country’s architecture unique and awe-inspiring.

Nature

Toyo Ito, the 2013 recipient of the Pritzker Architecture Prize, is one such Japanese architect who exhibits a sense of spirit in most of his works. His Meiso No Mori Municipal Funeral Hall is a thin-shelled concrete canopy that exquisitely blends with the undulating hills behind it. Rather than compete for attention, the built structure complements nature.

In the words of architectural educator Georg Windeck, “This timeless character forces the inhabitant to search for an understanding of the architecture as a found landscape, rather than a built creation.”

Asymmetry

In line with natural design, Japanese architecture does not force symmetry onto built forms. As irregularity remains abundant in the environment, the Japanese celebrate it rather than correct it. The concept is based on their world view called the wabi-sabi, which accepts the imperfection of life. Wabi means “rustic simplicity” while sabi translates to “taking pleasure in the imperfect.”

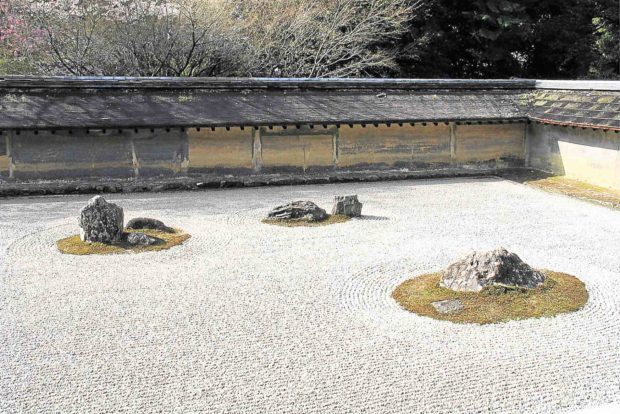

This concept is best expressed in Japanese gardens. Rocks are isolated and placed around a sand-filled pit. The garden may look bare at first glance, but the emptiness actually creates a breathing space that becomes conducive to contemplation. Trees are planted without formal arrangement, allowing them to grow organically. The built and the natural remain seamless, allowing both to thrive under any circumstance. In this sense, the asymmetry of built forms demonstrates Zen Buddhism.

Simplicity

Marie Kondo, organizer extraordinaire and bringer of good cheer, hails from Japan. Her method recently found popularity across the world due to its spiritual take on decluttering. She practices one of the things the people of Japan are known for: minimalism.

Emptiness

For the Japanese, a bare room does not express poverty. Rather, the void space is used to emphasize the importance of things to allow an artwork or a focal piece to shine in a room. Emptiness also serves as a breathing space. It allows people to relax in a garden or to carry out their activity without obstruction. The Japanese people celebrate emptiness and use it to reveal what is truly valuable.

The traditional Japanese residence is one of the best examples that demonstrate this concept. In a traditional home, the rooms are often bare of furniture and are divided by partitions made out of Japanese paper. Each room features tatami mat flooring—woven reeds with a straw core.

Unconventional

Though Japanese architecture is often stereotyped as minimalist and simple, you’ll be surprised to know that there are several designers who defy all these characteristics. Modern firms such as Atelier Tekuto and Terunobu Fujimori seek to challenge convention.

The first group explores complex shapes and angles to create spaces which are literally out-of-the-box. One such work that exhibits love for unique design is the Polygonal House in Tokyo.

Terunobo Fujimoro, meanwhile, is a Japanese architect considered eccentric by traditionalists. His designs, however, remain connected with nature like many of his Japanese colleagues. The difference is that he takes nature and drives it to the extreme. His works are eye-catching yet remain blended with the landscape.

One example is the Charred Cedar house which utilizes burnt wood to protect the residents from rot and rain. His own house is reflective of his ideals: the Tanpopo House features volcanic rock walls and a grass roof. He is definitely one interesting architect.

Overall, Japanese aesthetics is admired for its simplicity, functionality and spirit. Whether traditional or unconventional, the works of the Japanese are usually created with much thought and consideration. These creations reflect a kind of harmony that is not always found in other cultures.

From their architecture to their art, the Japanese showcase their values and beliefs. Their creations become expressions of their religiosity and sets them apart from the rest of the world.

Sources: “Construction Matters” (powerhouse Books, 2016) by Georg Windeck; toyo-ito.co.jp; architizer.com; Stephane D’Alu, Daderot via Wikimedia Commons; Ryushi Kojima; goodfreephotos.com; Forgemind Archimedia via Flickr.com