Structural marvels of learning

The structural design of school buildings has evolved to adapt to the needs of its time.

Many educational institutions feature classical designs, which have been preserved for their architectural heritage and aesthetic value. Modern structures, meanwhile, were built with the promise of cost-efficient, smart, and environmentally sound design and technologies that can provide a healthier place for students to learn and interact.

Here are such school buildings that do not only evoke a sense of history, but also provide a sustainable environment conducive to learning.

The Nicanor Reyes Hall, Far Eastern University, Manila

The Nicanor Reyes Hall, named after the founder of the Far Eastern University (FEU), is the oldest and most valued structure on the FEU campus, for it is a remnant of the original Art Deco architectural design back in its founding years.

Described as “an exercise in architectural virility,” a historical essay in the CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art says, “Boldly projecting piers at each end of the front support the dominant horizontal block that defines and shelters the wide expanse of the building. The interlocking of horizontal and vertical elements creates both movement and stability.”

The building was constructed in 1939 by National Artist Arch. Pablo Antonio who later designed four more buildings—the Girls’ High School Building in 1940, Boys’ High School Building in 1941, the Auditorium and Administration Building in 1949, and the Science Building in 1950.

The complex is considered the largest body of work done in Art Deco style in Manila, thanks to the restoration project led by FEU chair Lourdes Reyes Montinola. The campus structures were restored to their original appearance, with contemporary changes blending with the old.

The FEU conservation project won the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (Unesco) Asia Pacific Heritage Award for Cultural Heritage in 2005. Unesco cites the project as a good model to follow, noting that “…in the context of its immediate neighborhood, the project has had a significant effect on raising historic awareness in the community. The project maintained a commendable balance between preserving original building design and use while accommodating the university’s modern needs.”

St. La Salle Building, De La Salle University, Manila

Nestled in the heart of Manila, St. La Salle Building is DLSU’s heritage building. It is named after St. John Baptist de La Salle who is credited as one of the founders of modern classroom-style education and founder of the Brothers of the Christian Schools.

This historical landmark along the busy Taft Avenue is an H-shaped four-storey neoclassical structure built from 1920 to 1924 to serve as the new campus of then De La Salle College to accommodate its increasing student population. The original three-storey building was designed by Don Tomas Mapúa, the country’s first registered architect.

An international publication even listed St. La Salle Building on the 2008 edition of “1001 Buildings You Must See Before You Die: The World’s Architectural Masterpieces”, which was written by Mark Irving.

The entry on St. La Salle Building says: “A triangular pediment crowns an entablature of cornice, frieze and architrave supported by Corinthian columns to create a three-bay portico main entrance…Wide, open-air portico wings extend from either side; the square openings on the third floor balanced over the rectangular openings of the upper floors’ balustrade level. Corinthian pilasters and a dentiled cornice unite the floors between each arch.”

Augusto Villalon, architect and heritage conservation advocate, was quoted in an Inquirer report as saying, that what the book tries to say in plain English is that Mapúa took classical Greek architecture influences and simplified them to fit the modern lifestyle and building technology of 1920s Manila. He adapted a Western architectural style to suit the tropical environment of the Philippines.

Ewha Campus Complex (ECC), Seoul, South Korea

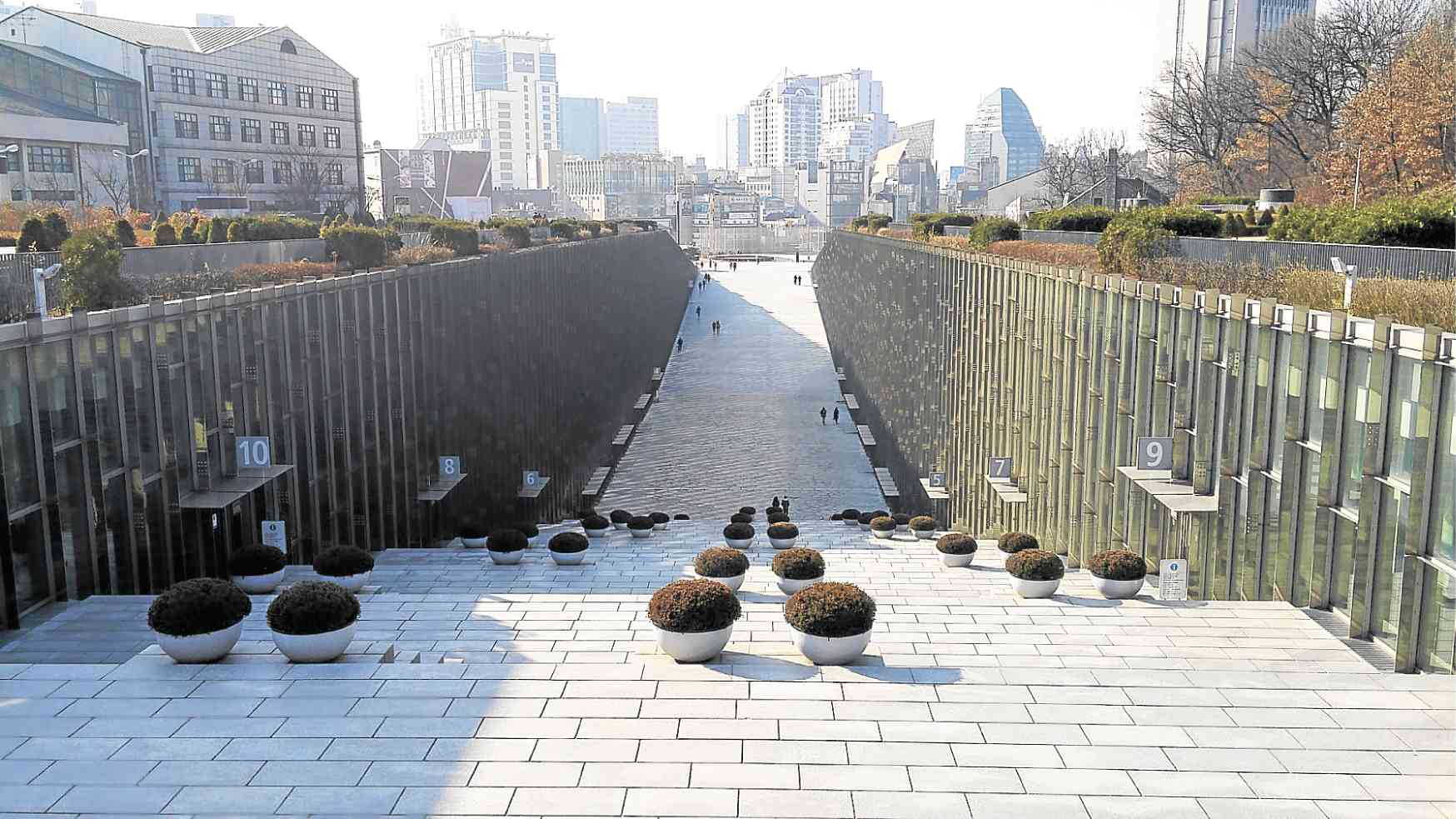

Opened in 2008, the campus center of Ewha Womans University in Seoul is considered the largest environment-friendly underground campus facility in South Korea. Despite being an underground structure, the center is designed to look as if it was built above ground.

Forming a gentle slope, the unique glazed structure surrounds a long passageway. A sustainable feature of the center is that it stays warm during winter and cool during summer. It has six underground floors and houses the study halls, lecture halls, exhibition halls, a bookstore and a film and performing arts theater.

The campus building was designed by French architect Dominique Perrault, who also designed the famed French National Library and other landmarks in Europe. ECC was his first project in Asia. It won the Grand Prize for 2008 Seoul Architecture Award, 2009 Green Good Design Award, and AFEX (Architectes Français à L’Export) French World Architecture Grand Prix in 2010.

The Hive, Nanyang Technological University, Singapore

Nanyang Technology University’s The Learning Hub South—also called the Hive as it resembles a cluster of elongated bee hives—was designed by Heatherwick Studio and executed by lead architect CPG Consultants.

Completed in 2015, this educational landmark in Singapore has twelve towers, each a stack of rounded tutorial rooms that taper inwards at their base around a public central atrium to provide 56 tutorial rooms without corners or obvious fronts or backs. The rooms were designed to be corner-less to promote more interactive learning.

Instead of corridors, each level features open galleries where students can circulate and meet. And instead of a conventional entrance, the building is porous at the ground level, meaning people can approach and enter from any direction.

And in the efforts of NTU to be the greenest campus in the world, it is the first building in Singapore to adopt “passive displacement ventilation system” wherein no fans are needed to distribute air. Instead, the building has special metal coils with cold water flowing through them. This cools the wind that enters the classroom and removes hot air via convection. The openings between pods also allow for natural ventilation to the atrium, corridors, staircases, and lift lobby.

The hive is also built like a garden campus with lots of natural foliage in its interiors and rooftop terraces. Other energy-saving features include energy-efficient light and motion sensors in classrooms, toilets and staircases, a building layout that maximizes natural light.

It received in 2013 the Green Mark Platinum Award from the Building and Construction Authority (BCA), Singapore’s national benchmark for the design, construction and operation of high performance green buildings.

University of Ottawa Social Sciences Building, Ottawa, Canada

Completed in 2012, the new Social Sciences Building of the University of Ottawa is another eco-friendly structure with a design that addresses the challenges of its dense urban location in the capital city of Canada.

The 15-storey building met strict environmental guidelines, receiving a gold-level certification under the Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design (LEED) program, a green building rating system created by the US Green Building Council. It is home to North America’s largest “living wall” composed of plants that act as an air filtration system, and has significantly reduced its energy consumption by 50 percent.

The structure connects the Faculty of Social Sciences’ nine academic departments and six research centers via walkways. It includes a theater, classrooms, multipurpose rooms and two atriums, which are wide, open areas with glazed walls to let natural light in.

Designed by Diamond Schmitt Architects and KWC Architects, the building won the Interior Green Wall Award of Excellence and Institutional Building Award at the Ontario Concrete Awards, both in 2014.

Low Library, Columbia University, New York

The Low Library, named after Columbia President Seth Low, is one of Columbia University’s most iconic buildings.

Built in 1897, it is patterned loosely on the Classical Pantheon, with its columns and domed roof, the largest all-granite dome in the United States. Perched in the middle of the steps of the Low Library is the “Alma Mater”—the bronze statue unveiled in 1903 which has since then become the most familiar symbol greeting the thousands of visitors that entered the university’s gates.

Almost immediately, Alma Mater became known for the tiny, hidden owl buried in the folds of her skirts. There has been debates of its significance. Why was it included in its design? Many male students (until 1983, Columbia admitted only men) joked that any student who found the owl would marry a Barnard girl (from Barnard College, a private women’s liberal arts college located in Manhattan, New York City). The other legend is that the first student every year to find the owl hidden in her robes will become valedictorian.

Today, the Alma Mater statue remains a popular New York tourist site and a prominent campus symbol. One can pass through the campus at any part of the day and see visitors taking photos next to the century-old landmark.

No longer a library, Low Library houses the Visitors Center and the Office of the President and other university officials. It is used for campus events and is a favorite hangout of students.

Sources: Inquirer Archives, CCP Encyclopedia of Philippine Art Volume III, DLSU Student Handbook 2018-2021, ecocampus.ntu.edu.sg, heatherwick.com, ewha.ac.kr, perraultarchitecture.com, english.visitseoul.net, socialsciences.uottawa.ca, usgbc.org, dsai.ca, columbia.edu