As someone who was once in your shoes over 30 years ago, I know how significant this milestone is, that we are celebrating today for all of you who worked hard to earn the degrees you are receiving today.

Many of you have looked forward to this day with trepidation and excitement—and maybe a little fear—as you close one chapter of your young lives and begin writing the next pages of your respective stories.

All of you, without exception, deserve to be here. You were the ones who attended class, studied late for your exams and worked hard to write your papers.

No one can take that away from you, and you should all take time to sit back and revel in what you have accomplished.

Life lessons

Be that as it may, it is also a good time to look back and remember all those who helped you along the way: your parents, your teachers and mentors, and all those who, in one way or the other, contributed to your education.

My father, John Gokongwei, Jr., imparted many life lessons to me as well, and one of them is to be grateful.

So, I encourage all of you to recognize and acknowledge the people and the institutions that provided the opportunities that made this day possible—including the support extended by the leadership of the Valenzuela City government to PLV.

My father has always believed that we should invest in education and that we should help educate others—and without a doubt—he would approve of the city government’s efforts to provide accessible, quality education to the people of Valenzuela.

It is no secret that my father has and continues to place a great premium on education.

For example, when he saw that his younger brother, my Uncle James Go, who is currently my boss as chairman of JG Summit, our holdings company, was doing well in school, my father encouraged him to enroll in the top engineering school in the United States, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Likewise, when he saw that I was highly motivated and I was getting pretty good grades, he supported my studies in the Wharton School of Business at the University of Pennsylvania.

Given my father’s enthusiastic support for education, as evidenced in the grants his foundation, the Gokongwei Brothers Foundation, has given to several universities and the hundreds of scholarships handed out to deserving students, it surprises many that my father was already at the ripe and still fighting age of 51 when he earned his diploma.

Interrupted education

Unlike those of you graduating today, he was not able to go to college immediately when he was younger because his father had died when he was only 13 years old.

As the eldest of six, my father took it upon himself to take care of his mother, his four brothers and his sister.

Rarely do tales that begin with hardship and tragedy come with happy endings, but my father refused to let adversity determine the outcome of his life and the lives of his family.

Circumstances tore his family apart, including the second world war, as his younger siblings had to live with relatives in China while he tried to eke out a living in Cebu so that he can support them.

When he was 15, he got on a bicycle every day to head to the marketplace to sell thread, soap, candles and other things he felt people needed.

He woke up earlier than anybody else and worked longer than anybody else.

He had no choice but to make the most of the hand he was dealt, because he learned early on what we, his children, would later learn ourselves: if you don’t work, you don’t eat.

So my father worked hard, traveling as many as two weeks on a small boat called a “batel” from Cebu to Lucena, after which he had to commute six hours from Lucena to Manila just to sell his wares.

That work ethic, more than anything, was the foundation of his success—and it was this same work ethic he would try to pass on to myself and to my siblings.

Just as life did not give my father everything, he made sure that we, his children, would not get anything on a silver platter.

If we wanted something, we had to earn it. We did not get large allowances when we were in school, nor did we get cash for our birthdays or for Christmas.

When we graduated from school, we were no longer given allowances; if we wanted to have money to spend, we had to work for it.

There would be no high-level positions waiting for me nor my siblings when we finished school.

Management trainee

When I got back from college at the University of Pennsylvania, I started work as management trainee in our food division.

Basically, that meant I had to go out and sell Jack ‘n Jill snacks to supermarkets, groceries, and “sari-sari” stores.

I was paid P2,000 a month. Since I had to go around the city, Dad let me use an old car, not even a Nissan, but a Datsun at that time, with a broken air conditioner.

I may have been the son of the boss, but I worked harder than anybody else to prove that I wasn’t just the son of the boss.

My father believed that for us to appreciate the different nuances of our businesses, we had to start from the bottom and get our hands dirty.

My sister Robina started out as a clerk in the bodega of Robinsons Department Store. My other sister Marcia scooped ice cream at one of our old Presto outlets when she was in high school.

Today, Robina is in charge of our entire Robinsons retail business, while Marcia is one of the leading executives of our food manufacturing business.

As for myself, I am willing to bet that I have held more bras than any man or woman here today—because one of my first jobs was to put the price tags on women’s bras in our department stores.

But seriously, this and other jobs I held in my father’s companies is what made me appreciate the dignity and value of work.

If I took the time to relate to you the story of my father and how he has imbued in us the dignity and the appreciation of the value of perseverance, hard work and labor, it is because I believe this is what will set you apart from all the rest of the students graduating this summer in the Philippines and elsewhere in the world.

As the saying in theater goes, there are no small roles—just small actors. The same goes with work.

There are no insignificant jobs—just inconsequential workers. This, I believe, is at the core of professionalism: a commitment to pour your heart and soul into doing your job, and doing it the best way you can.

Professionalism

It means being competent and knowing your job, inside out. It means being able to deliver quality work on time, all the time. It means abandoning the philosophy of “pwede na” and adopting a “100% or nothing” approach to your work.

Professionalism also involves how you interact with your colleagues and learning how to be a team player.

When I was starting in our company, I may be the boss’ son but I never pulled rank on anyone. I was just a member of the team like everyone else.

I was even a member of our company basketball team but I was so bad that they never let me play on the court unless the other team was already so far ahead.

But practicing and playing with my colleagues helped me develop good relationships with them.

That teamwork we have developed was brought from the basketball court back to our

office.

We all learned to work together, which led us to many successes as a company.

In school, sometimes when you’re assigned to do work in groups, sometimes it’s possible to talk to your teacher and ask that you be allowed to submit a separate paper or project because you don’t get along with your projectmates.

In the workplace, it does not work that way. You have to learn how to appreciate that you are part of a team and acknowledge that everyone has a role to play to ensure the competitiveness and success of the organization—and that it is your responsibility to bring out the best in others, not just yourselves.

Professionalism also demands integrity, honesty and accountability—the willingness to take responsibility for your own actions and having the courage to do what is right, not just when things are okay, but especially when things are not going well.

The importance we attach to professionalism is the reason why we in our company, JG Summit, value attitude just as much as aptitude.

If you study those who have succeeded in their respective fields, you will find that there are ordinary individuals who have managed to work their way to the top, just as there are talented people who have failed to realize their potential.

As cliché as it sounds, it has been proven time and again that hard work beats talent when talent does not work hard. Hard work beats talent when talent does not work hard.

If there is something I have learned in my many years of working in the family’s many businesses, is that it doesn’t really matter what school you graduate from, it only matters where you want to go—and it is easy to spot those who are motivated and driven to excel.

That’s why in our company, we have a healthy mix of graduates or alumni from the various different schools, not only those coming the usual main schools in the country, but also those who have come from

the top and promising institutions of higher learning found all over the country from Aparri to Jolo.

And these are the people who have propelled JG Summit to become one of the leading conglomerates here in the country.

I will not sugarcoat reality and tell you that life is always fair and that if you work hard, your work will immediately be recognized and rewarded.

Life is rarely fair, and sometimes your hard work will not be appreciated; and maybe, years from now, when things are not going your way, you are going to say that everything

I said here today about work ethic and professionalism

only applies to a select, fortunate few.

If and when that happens, keep in mind that for every success my family has earned, there have been numerous setbacks that would have altered the fate of JG Summit if my family had allowed these failures to dictate our actions moving forward.

Failures

But my father has always hammered the point that the road to success is littered with failures.

It is inevitable, especially when you dream big.

Remember, however, that ultimately you will be remembered for what you have accomplished, not for what you have failed to achieve.

For it is not how many times you stumbled or failed but rather how many times you have stood up and attempted to try.

And in standing up, in rising up, you have already succeeded and that the odds are you will accomplish what it is you wish to accomplish.

Today, few people remember our failed businesses.

You can ask your parents if they know Presto Ice Cream, or Litton Mills, and Robina Chicken and I’m sure they would hardly remember these companies or brands—but today everyone knows Cebu Pacific, Robinsons Malls, Jack and Jill and C2.

Let me end with two parting thoughts. As you millennials like to say, and I consider myself a millennial also, YOLO—you only live once.

Challenge the incumbent

First, in this complex world, do not let the odds or challenges dissuade you from pursuing your passions.

I constantly remind myself of this, now that I’m the head of a big company, responsible for 40,000 of my people, we need to continue to act as a small company, as a challenger, so that we can continue to challenge the incumbent, shake the status quo, find and satisfy the unmet need—which is what has powered JG Summit to where it is today and it will be the same formula that will topple companies like us or continue to propel us to greater heights.

This formula equally applies to you whether you are an entrepreneur or in your career as a professional.

And second, keep on learning. As you begin the next chapter of your lives, keep in mind that you will have to continue learning even after you have left this prestigious university.

Learning is a continuous process because the world is ever-changing and you have to keep abreast with developments.

While the degrees you earned today are indeed a cause for celebration, the explosion of information and the velocity of change driven primarily by technology requires us to have a mind-set of continuous learning.

A lifelong learning mind-set is your insurance against your obsolescence, including the rendering of your degrees today as completely obsolete in the future.

And lifelong learning is all about having that insatiable appetite for reading, experimenting, experiencing, trying, failing, stretching, adapting and asking.

You have been given a fresh start and blank pages—now where your journey takes you and how it ends is all up to you.

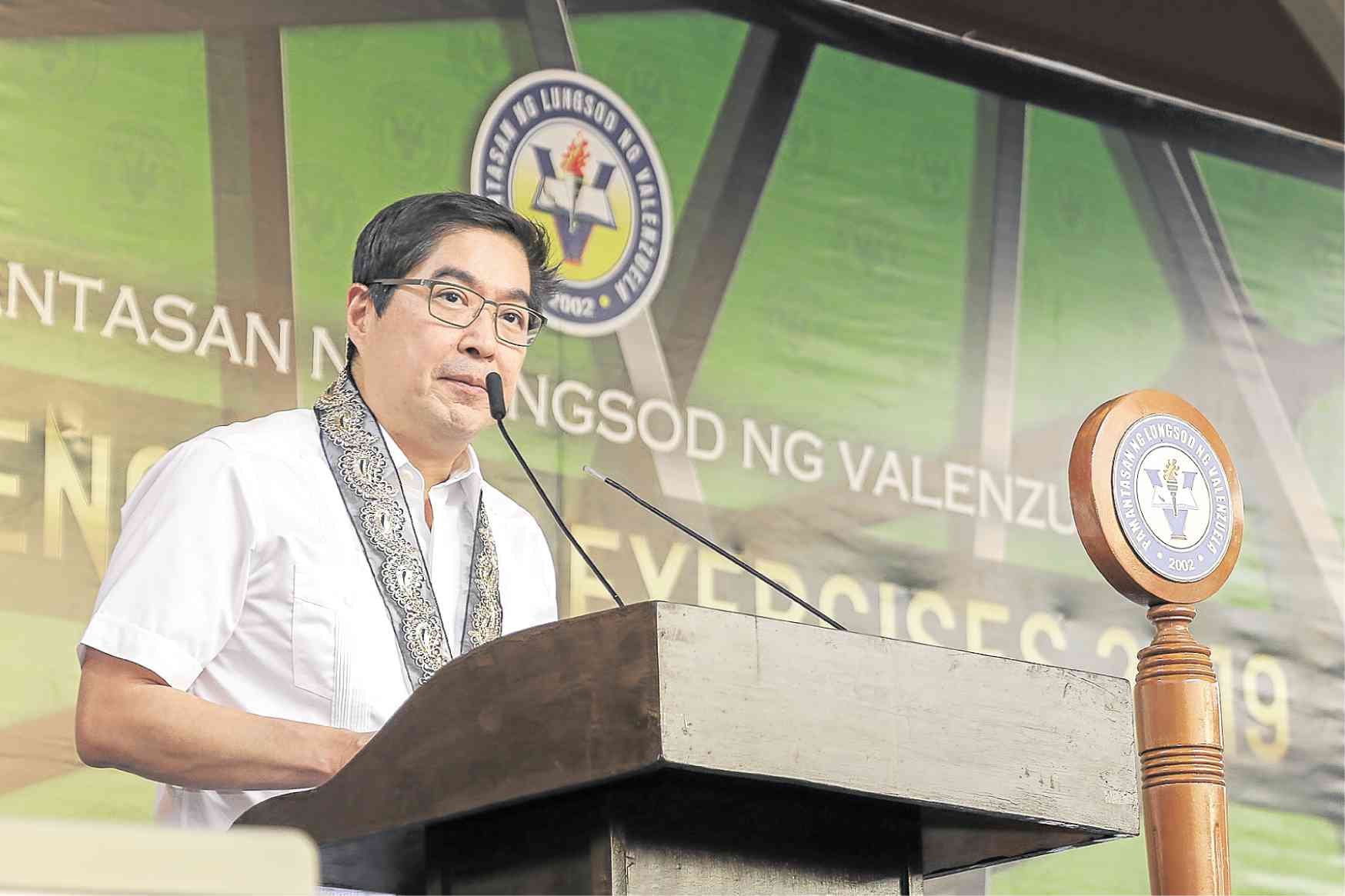

Gokongwei is the chief executive officer of JG Summit Holdings Inc. and delivered this commencement address at Pamantasan ng Lungsod ng Valenzuela on April 30, 2019.