Devastating ‘faults’ of the ‘Big One’

Rescuers pull out one male survivor at the rubble of Chuzon Supermarket in Porac, Pampanga. —GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

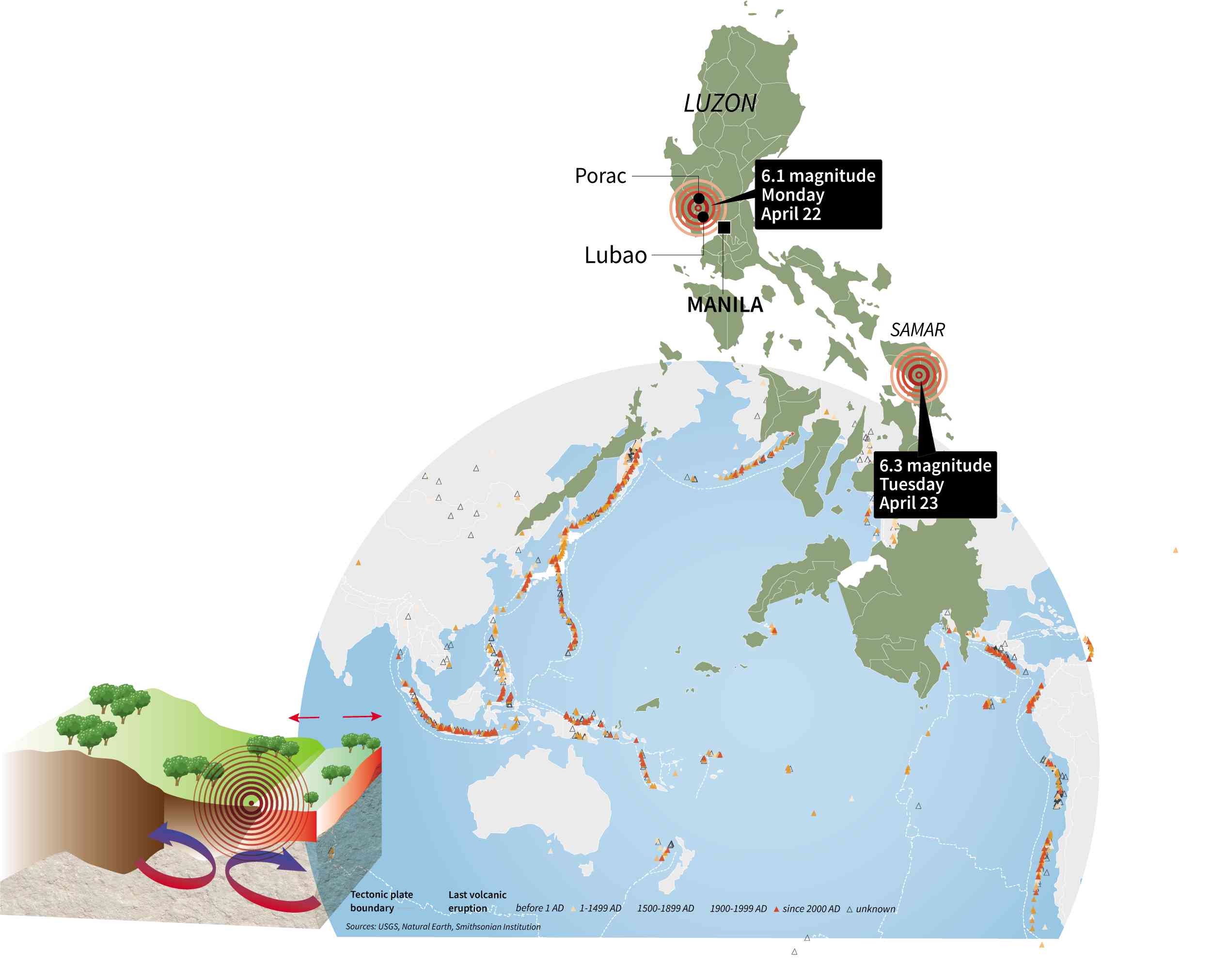

Earthquakes occur quite frequently in the Philippines due largely to its location.

The country lies along the “Pacific Ring of Fire,” home to several tectonic plate boundaries that stretch from Indonesia to the coast of Chile within a 40,000-km arc of seismic violence that triggers volcanic eruptions and unleashes earthquakes almost every day.

Three tectonic plates that encircle the country are the Philippine Plate in the East; the Eurasian Plate in the West; and the Indo-Australian Plate in the South. The existence of several fault lines across the country is a manifestation of the movements of these tectonic plates.

A fault line is defined as a geological fracture wherein the movement of masses of rock has displaced parts of the Earth’s crust. A rapid movement of a fault line may produce a powerful energy that can trigger a strong earthquake.

There are five active fault lines in the country namely the Western Philippine Fault, the Eastern Philippine Fault, the South of Mindanao Fault, Central Philippine Fault and the Marikina/Valley Fault System.

‘The Big One’

In Metro Manila, the “Big One” applies to a scenario wherein movements along the Valley Fault System could trigger a 7.2-magnitude quake. The East Valley Fault straddles 10 kilometers in Rizal province while the West Valley Fault runs over more than 100 km through the provinces of Bulacan, Rizal, Cavite and Laguna, and Metro Manila.

Scientists claimed that the 100-km fault, which last moved in 1658, moves every 400 years, meaning the threat of a 7.2-magnitude quake is getting closer.

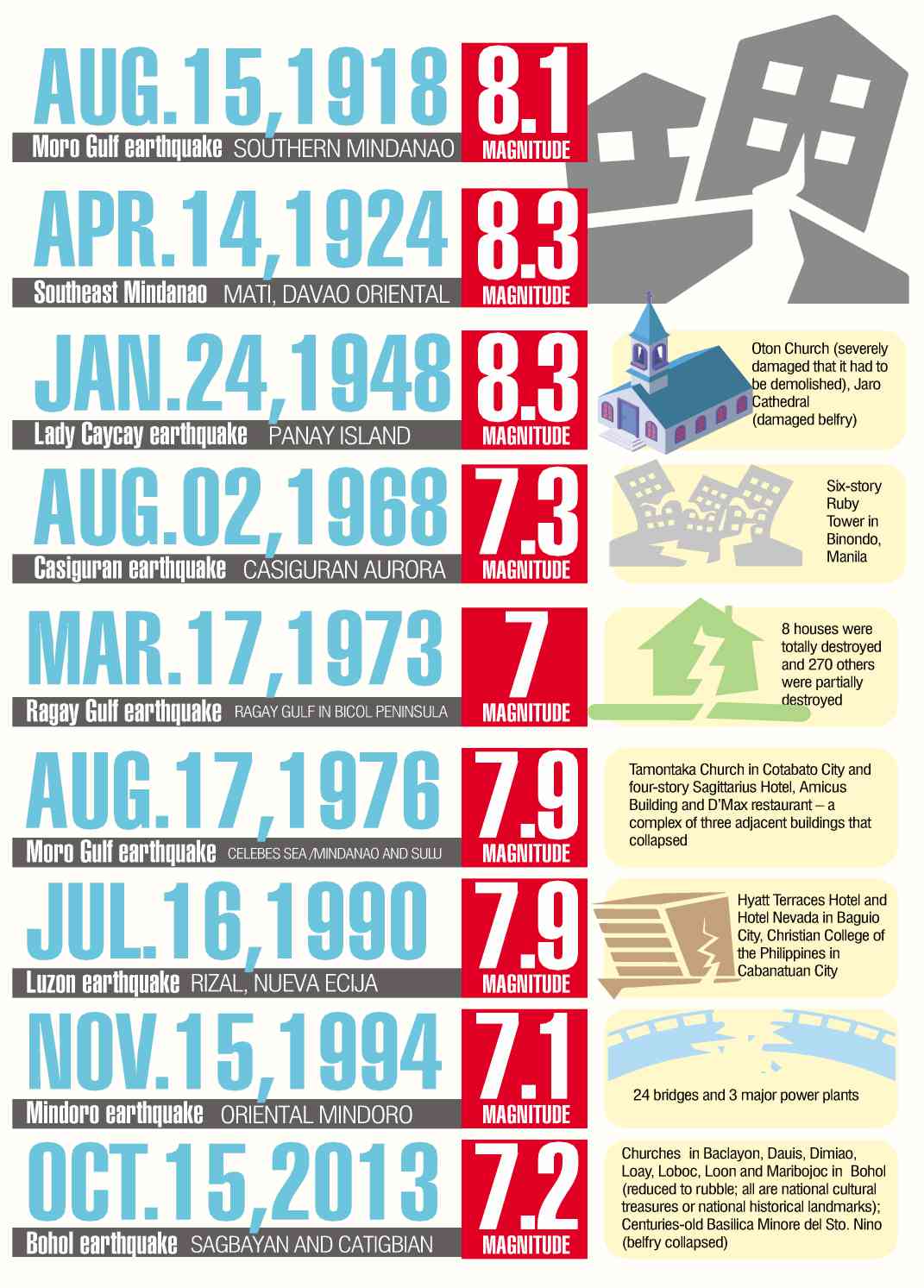

Over the years, the Philippines has suffered a history of destructive and frequent earthquakes. Destruction of buildings and the loss of lives are not limited to the epicenter and nearby cities of the earthquake.

On Aug. 2, 1968, an earthquake, felt at Intensity 8, had its epicenter in Casiguran, Aurora. But it was felt as far as Manila, where 270 people were killed and 261 others were hurt mostly due to the collapse of the Ruby Tower in the Binondo district.

On Mar. 17, 1973, the municipality of Calauag in Quezon province was the worst hit by a 7.0-magnitude earthquake that struck Ragay Gulf. At least 98 houses were totally destroyed and 270 others were partially damaged. In Brgy. Sumulong in the same town, 70 percent of the school buildings were damaged.

A 7.9-magnitude earthquake on Aug. 17, 1976 left more than 5,000 dead; 2,288 missing; and 9,928 injured in Regions IX and XII. The tremor happened just after midnight when most people were sleeping. A tsunami that devastated more than 700 km of coastline, struck from different directions, catching residents in the area unaware.

On Aug. 17, 1983, a 6.5-magnitude, Intensity 7 earthquake was felt in Laoag City and the municipality of Pasuquin in Ilocos Norte. A number of reinforced concrete buildings either totally crumbled or sustained major structural damage beyond rehabilitation. The most heavily damaged structures in Laoag City are those near the Laoag River flood plain and along reclaimed stream channels.

On Feb. 8, 1990, a 6.8-magnitude earthquake, which was felt at Intensity 8, hit the municipalities of Jagna, Duero and Guindulman in Bohol. About 3,000 houses, buildings and churches were damaged, of which 182 totally collapsed, including two historical churches.

The bridge connecting Jagna and Duero also collapsed while the roads to the municipality of Anda sustained cracks and fissuring. Landslides and rockfalls blocked portions of the roads that caused inaccessibility to some areas between Anda and Garcia Hernandez. Six fatalities were reported and more than 200 were injured. About 46,000 people were displaced and at least 7,000 of them were rendered homeless. Damages to property was estimated to reach P154 million.

The 7.7-magnitude earthquake on July 16, 1990 shook the northern part of Luzon. Caused by strikes and slips in the Digdig Fault and with an epicenter in Nueva Ecija province, the earthquake devastated Baguio City, which was 50 km away.

Damage to buildings, infrastructure and property, mostly in Dagupan City and Baguio City, amounted to roughly P10 billion. At least 1,621 were killed. The 1990 earthquake prompted the Philippine Institute of Volcanology and Seismology to develop a software for Rapid Earthquake Damage Assessment System.

On Nov. 15, 1994, a 7.1-magnitude earthquake affected 13 municipalities or a total of 273 barangays in Oriental Mindoro. About 22,452 families were affected, 78 people were killed and 430 were injured.

PACIFIC RING OF FIRE The Ring of Fire is a major area in the basin of the Pacific Ocean where many earthquakes and volcanic eruptions occur. The western portion is more complex, with a number of smaller tectonic plates that collide with the Pacific plate from Mariana Islands, the Philippines, Bougainville, Tonga, and New Zealand. Movements within the Earth’s crust cause stress to build up at weak points, and rocks to deform.

Damaged infrastructure include 24 bridges, eight of which were rendered impassable for days, isolating villages and towns. Three major power plants, two of which are connected to the Luzon grid and one to the Visayas grid, tripped during the earthquake, causing brownouts in Mindoro Island and parts of Leyte and Samar.

A 5.1-magnitude earthquake, felt at an Intensity 7, rocked Bayugan, Agusan del Sur province on June 7, 1999.

Poorly built structures collapsed, while posts and foundations of buildings sank or tilted. Two days later, a 5.0-magnitude earthquake was felt at Intensity 6 in Talacogon, Agusan del Sur. The earthquake caused damages to bridges, roads, schools, a commercial complex, a telephone station and the municipal hall of the town of Talacogon.

On Oct. 15, 2013, the 7.2-magnitude earthquake, felt at Intensity 7, in Tagbilaran City, Bohol caused major destruction in the province. This was one of the strongest earthquakes to hit the country in recent years. Total damage was estimated at over P2.2 billion, devastating Central Visayas particularly the provinces of Bohol and Cebu.

More than 200 persons were killed and over 14,000 structures, including historical buildings and churches were destroyed.

Phivolcs described the Intensity 7 tremor as destructive, frightening people and causing them to run outdoors for safety.

“People find it difficult to stand in upper floors. Heavy objects and furniture overturn or topple. Big church bells may ring. Old or poorly built structures suffer considerable damage. Some well-built structures are slightly damaged. Some cracks may appear on dikes, fish ponds, road surfaces, or concrete hollow block walls. Limited liquefaction, lateral spreading and landslides are observed. Trees are shaken strongly,” Phivolcs earlier said.

The agency defined liquefaction as a process wherein loose saturated sand lose strength during an earthquake and behave like liquid.

Sources: Inquirer Archives, phivolcs.gov.ph, pna.gov.ph Kathleen de Villa and Marielle Medina, Inquirer Research

Major earthquakes

Earthquakes with a 7 to 8 magnitude are considered as major quakes that can cause considerable damage near the epicenter. Shallow-seated or near-surface major earthquakes when they occur under the sea, may generate tsunamis.

Aftershocks are those that occur after the largest shock of an earthquake series. These are smaller than the main shock and may continue over a period of weeks, months, or even years. Earthquakes are said to come unexpectedly, shock after shock.

The Philippines has done little in updating its building code, which would have enabled structures in the country to better adapt to the destructive forces of nature. Issues and concerns over the implementation and proper inspection of buildings and houses during construction also remain.

“We are better prepared than before,” Phivolcs Director Renato Solidum was earlier quoted as saying. “But we need to do more. For earthquake preparedness, it’s not just the people who should be preparing, but the buildings have to also be structured properly.”

Local governments should be more strict in building inspection and in the issuance of permits for building design and construction, he further noted, adding that “we have a good building code, but unfortunately, this is not always followed.”

Solidum also emphasized the need to educate people, pointing out that “most people would not know the basic structural standards unless they are engineers.”

Sources: Inquirer Archives, Phivolcs, PNA, NCRPO