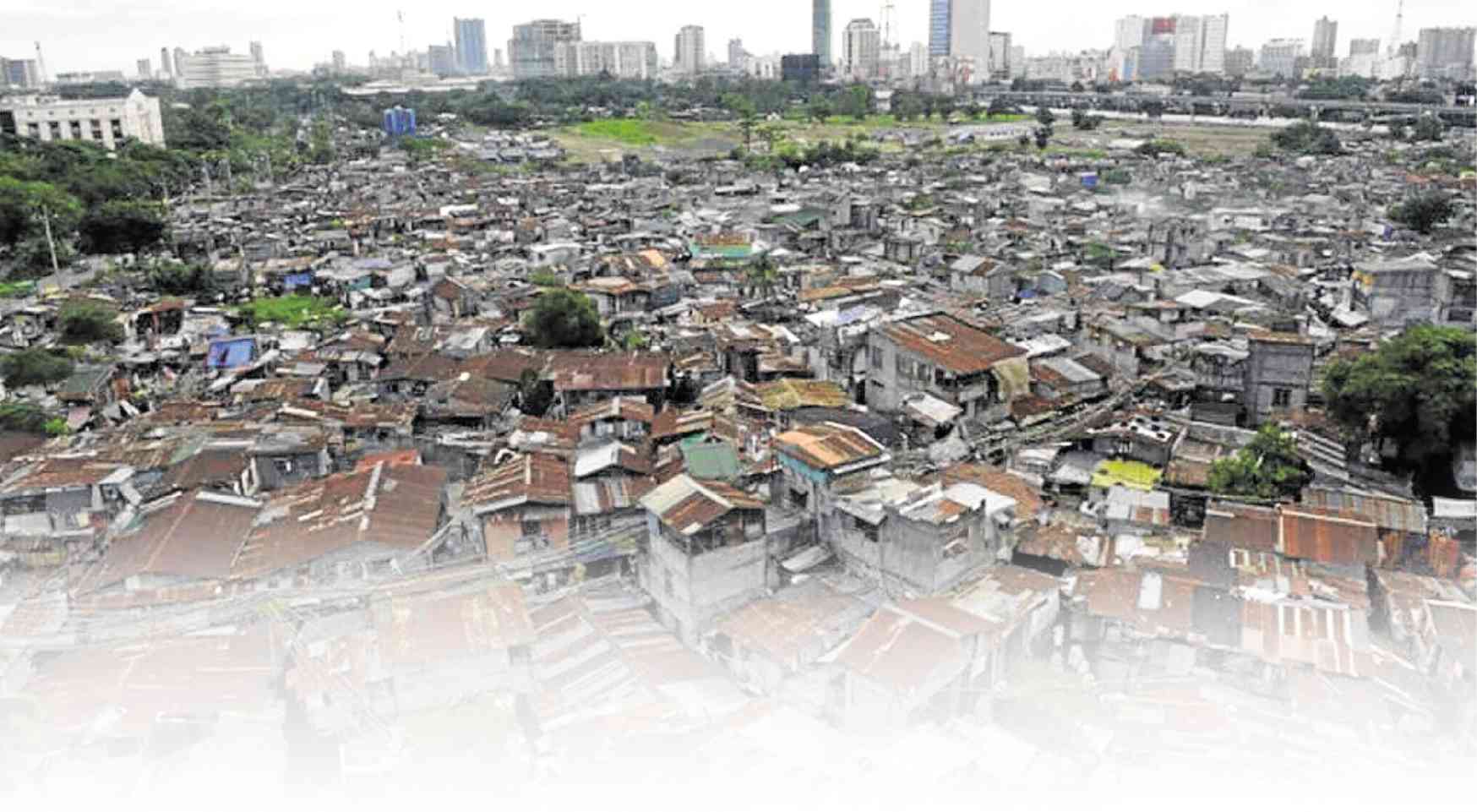

Building homes especially for poor Filipinos has remained a great challenge.

According to the National Economic Development Authority (Neda), the country’s total projected housing need for the period 2017-2022 stands at 6.57 million.

In 2017 alone, the actual housing need reached 1.018 million. Earlier studies identified the backlog to be mostly in the building of homes for low-income Filipinos.

The backlog stood at 6.7 million in 2015, and the new housing need for the period 2016 to 2030 is 5.6 million, according to a report “Impact of Housing Activities on the Philippine Economy” in September 2016 by Winston Padojinog, president of the University of Asia and the Pacific.

The study says that the 6.7 million backlog refers to housing units priced at P3 million and below: 786,984 for those who can’t afford, 1.3 million for socialized, 3.7 million for economic, and 918,280 for low cost.

Thus, a key strategy to solve the housing woes has been to provide socialized housing.

Section 3 of Republic Act. No. 7279, the Urban Development and Housing Act (Udha) of 1992, also known as the Lina Law, says that socialized housing refers to housing programs and projects covering houses and lots or homelots only undertaken by the government or the private sector for the underprivileged and homeless citizens, which shall include sites and services development, long-term financing, liberalized terms on interest payments.

To qualify for the program, a beneficiary must be a Filipino citizen, must be an underprivileged and homeless citizen, must not own any real property, and must not be a professional squatter or a member of squatting syndicates.

The Housing and Land Use Regulatory Board (HLURB) reported 126 socialized housing projects were licensed in 2017, with 59 projects licensed as main projects and 67 as compliance projects (by condominium and subdivision developers who are required to build socialized housing units).

On the other hand, the Neda reports that the housing sector agencies of the government completed over 212,000 socialized and about 49,000 low-cost housing units in 2017.

These accomplishments by the private sector and the government fell short of the thousands of units needed to be built.

For government housing, there are a number of recurring challenges according to Neda. Among these are low budget utilization, mismatch in housing demand and supply, and persistent threats of natural and human induced disasters.

The private sector socialized housing providers, on the other hand, had asked the government to give them incentives to build homes for low-income families by increasing the price ceiling for socialized housing.

The price ceiling of a socialized housing unit with horizontal development (subdivisions) was P450,000, and vertical development (condominiums) was P400,000.

In its Board Resolution No. 974 on Aug. 1, 2018, the HLURB increased the price ceiling range from P600,000 to P750,000 for socialized condominium projects, depending on the size and location.

Specifically, for the National Capital Region, San Jose del Monte City in Bulacan Province, Cainta and Antipolo City in Rizal Province, San Pedro City in Laguna, and Carmona and the cities of Imus and Bacoor in Cavite Province, the ceiling is P700,000 for 22 square meters and P750,000 for 24 sqm.

For other areas, the ceiling is P600,000 for 22 sqm, and P650,000 for 24 sqm.

But the board resolution also says that socialized housing projects-issued license to sell with unsold units and not built as well as below the recommended minimum lot area and floor area shall only be sold at the existing price ceiling of P450,000.

Also issued on the same day, Board Resolution No. 973 defined the new price ceiling range for socialized subdivision projects, depending on the gross floor area and lot area.

Single detached housing, duplex and single attached housing, and raw houses have a price ceiling range from P480,000 to P580,000.

Are these increases enough of an incentive for private developers for socialized housing?

From the government’s end, Neda says there is much to be done, like adopting frameworks for sustainable communities; implementing initiatives to address operational issues on government housing projects; implementing housing reforms; and strengthening partnerships among stakeholders to improve responsiveness in shelter provision during natural and human-induced disasters.

COMPILED BY MINERVA GENERALAO, INQUIRER RESEARCH DEPARTMENT HEAD

Sources: Inquirer Archives, HLURB 2017 Annual Report, https://hlurb.gov.ph/law-issuances/board-resolutions/, Neda 2017 Accomplishment Report in https://www.neda.gov.ph/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SER-Chap-12_as-of-March-27.pdf