It is a horror story business owners do not want to happen to themselves.

Many fledgling businesses rely on a tech-savvy employee to set up their e-commerce websites. Owners tacitly give their employee the blanket authority to register the company’s domain name, find the hosting company and administer the domain account.

Taking his cue from the owner’s show of trust, the employee (let’s call him Gary) proceeds to register the domain name under his own name and types in his personal e-mail address for the domain name account.

In time, the company’s website is set up and starts seeing a steady rise in monthly visitors, including online customers.

Everything is coming up roses, it seems.

Well, that is, until the business owner finds out—although belatedly—that the employee had either malicious intent on the company all along, or an axe to grind as well as the gall to retaliate before he exits the company.

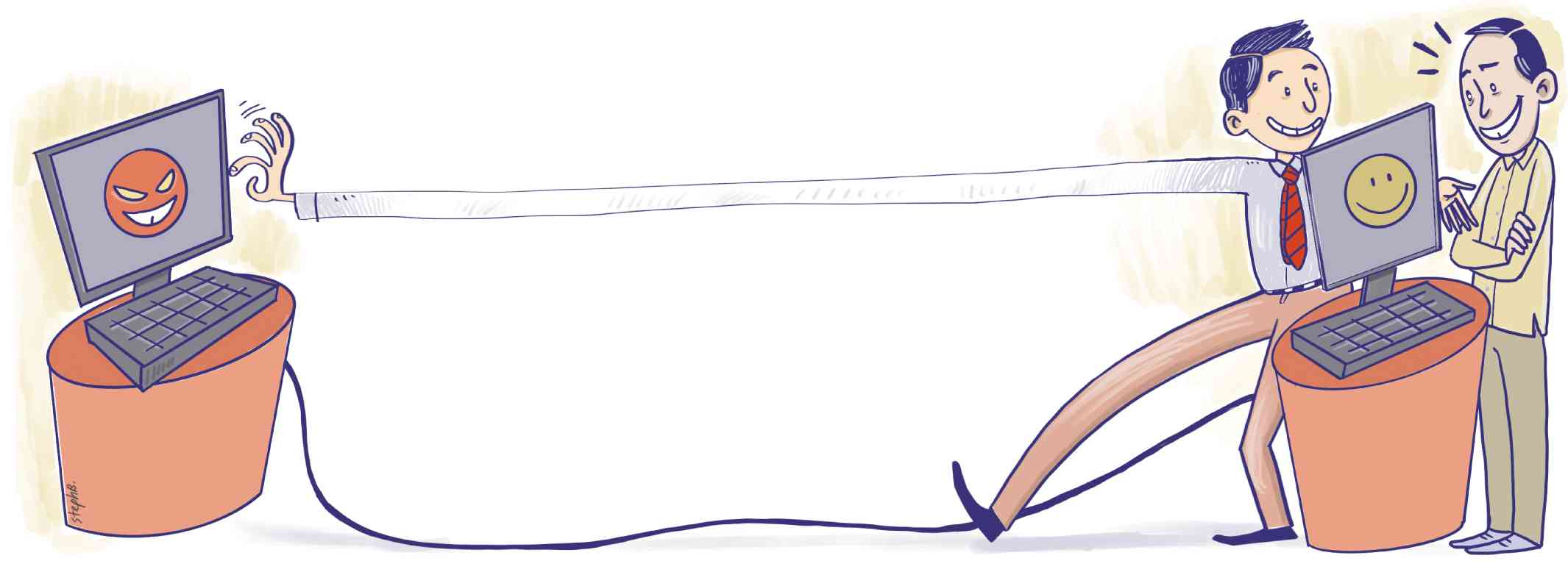

See, because our Gary character earlier registered the company’s domain name under his own name and now refuses to transfer the website’s registration to the company, he could easily disrupt or maliciously use the rightful owner’s internet services.

Or worse, he could make demands: He would only agree to turn over the domain name to the rightful owner in exchange for a sizeable amount of money.

There is a term for this new form of crime: domain squatting.

This refers to the acquisition of domain names in bad faith and intends to profit, mislead or destroy the reputation of someone else’s trademark.

Such online crime’s specter is all too real, although it is understandable why businesses seldom admit to being preyed upon by their own employees.

Our Cybercrime Prevention Act of 2012 imposes tough penalties on 16 types of cybercrime.

For instance, a person guilty of domain squatting against critical infrastructure may be imprisoned for at least 12 years and one day, or fined at least P500,000, or both.

While the cybercrime regulations are in place, there are only a few known cases of cybersquatting in the Philippines. In 2016, there was only one reported case of cybersquatting out of 3,951 complaints relating to cybercrime and cybercrime-related offenses.

Given this number, my guess on how many of these victims have instead opted to “buy back” their own domain name from the domain squatter is as good as yours.

It is ironic that corporate prey would prefer to pay off the criminal for the sake of convenience.

From a business perspective, I do understand the rationale. However, paying off a domain squatter to release a domain name is akin to paying off a hostage-taker in exchange for the life of a child.

This has to stop, or no one knows how many other businesses would be victimized by these cybercriminals.

To prevent opportunistic bad actors from holding businesses’ domain names captive, the solutions should have been simple: Owners, buy your domain name yourselves.

This is a way to ascertain that the domain name is registered in your company’s name, and it is your own e-mail address that is used for the registered account.

But if you ever have to ask an employee to do these for you, ask for documentation from the get-go. Please.

Despite this cautionary tale, I am thankful that these rotten eggs are more the exception than the rule.

Our Philippine IT industry—while small—is full of professionals with a noble mission, some for the common good even.

It is a tight-knit community where members openly share their startup ideas and foibles over a bottle of beer with peers, considering them as future partners rather than competitors.

Most of all, these are the good guys who, despite their talents and skills, still believe in and live by the “do no harm” principle.

Bad actors who break the community’s trust by doing harm have no place in this environment. —CONTRIBUTED