Efrille goes back to her hometown in Bohol only twice a year—once for new year, and then in August for her daughter’s birthday.

While others might see long distance relationships in the light of romance, her daughter first saw it in the tired eyes of her then-single mom coming home.

But Efrille Sarmiento, 36, is not an overseas Filipino worker (OFW). She works at a call center in Taguig, holding a high position that she landed after almost a decade.

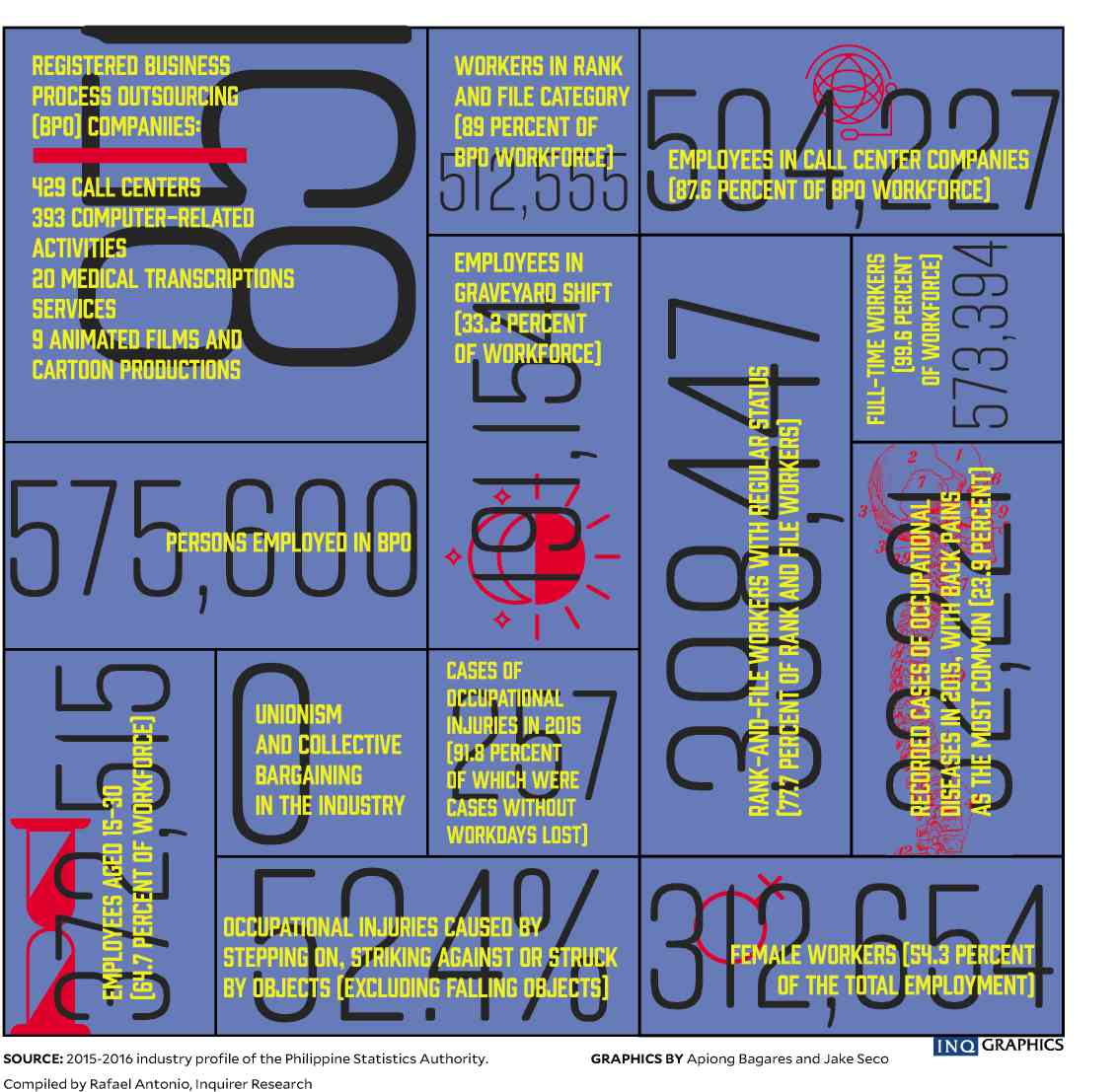

Hers is a story among countless others in the information technology and business process management (IT-BPM) industry, which has a workforce of more than a million Filipinos.

While there are officials who speak on behalf of the IT-BPM workforce, the real faces of this industry are often left unseen in broad daylight, given that many of them work the graveyard shift.

Their search for greener pastures is what helped grow the economy in recent years, along with the remittances of OFWs.

Efrille’s only child had gotten used to seeing her mom away for work since she was around four or five, although it wasn’t always an easy goodbye.

When Efrille got accepted as a call center agent in Cebu back in 2007, her daughter got sick after hearing the news.

Efrille had to postpone her first day on the job. But time off work is a luxury when you’re a single mom.

“I talked to her. I told her I have to do this because I wanted to give her what she wanted, what she needed, and what she deserved,” Efrille told the Inquirer.

“I can’t give her that if I stayed. She said yes, and then I left,” she said.

Getting Erap to say yes

A few years before Efrille’s career in the industry started, then President Joseph “Erap” Estrada and his Cabinet secretaries huddled in Malacañang to listen to a pitch related to his administration’s first business trip to the United States.

It was a small crowd in a big conference room, watching how an agent would answer questions from a sample call from the United States.

Maybe the officials did not know it then, but they were listening to what would later become an integral part of today’s economy.

“In a big conference room, we each set up a demo to explain to the Cabinet secretaries and [former] President Erap what we do,” said Karen Batungbacal, a pioneer in the industry, who was part of the team that made the pitch more than a decade ago.

Even back in 2000, the pitch showed that the industry was more than just voice calls, although this accounted for the bulk of industry operations.

For one, there were companies doing coding and medical transcriptions, too.

Batungbacal, who was heading a call center company that time, said that the industry needed to get Malacañang’s approval so it would have a better chance at getting a slice of the American market.

Before the Cabinet meeting, she first made the pitch to Erap’s Trade Secretary Mar Roxas, who would stay for years as a key ally to the industry, helping from birthing pains to raising it to new heights.

It was a promising chase.

The US market then had 3 million seats—or jobs, in other words—in customer service alone, she said.

The plan then was to get a part of that for the Philippines.

She herself tried in 2000 to go after the US market when she was the president and CEO of Customer Contact Center, Inc., a subsidiary of the Lopez group of companies.

“What I quickly found out when I tried to sell to the US market was that people didn’t know where the Philippines was. As I was writing to US firms, the responses I would get was what part of India was the Philippines,” she said.

This was why the industry needed government support. Before companies could get more US firms to outsource their services, the Philippines needed to put itself on the map first.

Malacañang fortunately approved the pitch.

Since then, she said the industry had joined trade missions under the Board of Investments.

According to the Information Technology and Business Process Association of the Philippines (Ibpap), of which Batungbacal is founding chairperson, the numbers grew since then.

The industry only had around 1,500 workers in 2000, while earning $24 million worth of revenues.

A number of developments helped paved the way for the industry, one of the most important of these is the Special Economic Zone Act, which Roxas previously amended to allow buildings to register as economic zones.

“This move would be a major enabler as it provided tax incentives to IT-BPM companies. Companies also received a one-stop shop support in the Philippine Economic Zone Authority, thereby making it easier to do business in the Philippines,” said Ibpap chair Lito Tayag in an e-mail.

“By 2011, the industry posted $11 billion in revenues, about 8.5 times the $1.3-billion level realized in 2004 and having already overtaken India as the No. 1 contact center destination,” Tayag said.

Then, in 2016, the industry made 1.14 million jobs, while revenues hit $22.9 billion.

By the end of that year, the industry had already been growing at a compound annual growth rate of 14 percent.

Two sides of same coin

The industry has clients from other parts of the world, but the US market currently accounts for around 70 percent of the demand in terms of Philippine IT-BPM services.

This is why a lot of IT-BPM workers had to adjust their sleep schedules, leaving for work while everyone else is already on their way home.

This was the world that Efrille entered when she got her first call center job in 2007.

While Batungbacal, dubbed the mother of the IT-BPM industry, traveled overseas to promote the Philippines, Efrille was at the office, answering questions about payroll with American clients for hours on end.

Sometimes, it could seem pointless. On one occasion, for example, Efrille said she had been talking to a client for four long hours, only to be told that the client would rather talk to a fellow American instead of a Filipino.

“We cannot route you to an American agent. If you want, you have an option to call back and see if you can get an American agent,” she would say.

This was normal then, she said, calling this “standard script” in the face of discrimination.

“No matter where you are, no matter how good you are, once they ask you where you’re from and you say Philippines, [this is what happens],” she said.

A promise pending

But this was her experience several years ago. And certainly, the industry became a better place to work for many reasons.

Around 18 years since that meeting in Malacañang, a somber tone now fills the air.

In his closing remarks during the International Innovation Summit in November, the industry event of the year, Tayag said the industry had grown slower than expected a year and a half since 2016.

“We believe that we were impacted by the wait-and-see attitude of investors and potential locators due to a number of geopolitical issues and the uncertainty over incentives rationalization,” he said at that time.

This means it’s been creating jobs and earning revenues at a slower pace, a predicament which has been largely pinned on the uncertainty brought about by tax reform.

Duterte’s treatment of the US government under the Obama administration after being criticized for his drug war did not help either, especially since the United States is the largest market of the Philippine IT-BPM industry.

The Duterte administration is now pushing for a tax package—the second in a series of tax bills—which will lower the corporate income tax while rationalizing tax perks.

This is the Tax Reform for Attracting Better and High-quality Opportunities (Trabaho) bill, a bill which ironically is projected to dampen the growth prospects of the industry.

After the November event, Ibpap president and CEO Rey Untal told reporters that the industry might have to revise its targets as numbers show that the industry has been underperforming.

Its 2022 road map targets 1.8 million direct jobs and $38.9 billion in revenues. It’s not clear if these targets are still within reach.

“Before, we could do a long-term projection with a fair amount of certainty. Right now, many of the analysts would stick to a two year cycle in terms of projections because of the dramatic shift in the landscape overall,” he said earlier.

Beyond revenues and jobs, investment pledges for new IT-BPM projects have been on a decline, official government data show. These pledges could have later on become actual foreign direct investments.

Most IT-BPM companies locate in buildings tagged as economic zones, where they are offered tax perks to attract them to set up shop here.

While the industry has the talent, it is also sensitive to government policies especially since it covers various business processes from the simplest to the most complex.

“That’s why it’s important for us to be located somewhere policymakers and regulators consider the peculiarities of our sector and business practices when they issue or enact policies,” an industry source said when asked for comment.

These incentives—on top of Filipino talent—played a key role in attracting more IT-BPM investments in economic zones, wherein the cost of

doing business is significantly lower than in areas outside ecozones.

But the promise of the industry years ago is the same promise it has now.

Batungbacal said she still thought that there are thousands of jobs to be made.

“We are desperately seeking government support because of the opportunities that are there. We are not yet giving up,” Batungbacal said.

Questions on artificial intelligence, tax reform, and freefalling investment pledges will eventually boil down to whether or not a million Filipinos could keep the light up at home.

For now, it has not come to that yet. Workers in the industry have other things to think about.

Efrille’s world is not the vast potential of the global industry, or the foreign companies that could tap the Philippines for outsourcing services.

Her world is a 14-year old kid at home in Bohol, who spent her childhood in the company of books instead of dolls she could play house with.

Sometimes, Efrille thinks about working abroad, an option that countless others took. But she keeps deciding against it.

“I can always find opportunities outside the Philippines. But I’m already far from my daughter. Why would I go farther away?” she said.

“I just want to be here,” Efrille said.