Art and nationalism have always been bound together,” wrote JJ Atencio in the book, “Nationalism and the Art of Jorge Pineda,” which he co-published with Rod Libunao. The book features nearly 30 paintings with nationalism as theme and with the purpose “to be able to pass on not only valuable works of art but also their more important message of love of country, nation and people.”

Atencio has always had an appreciation for art and history and growing up during the martial law era, he became familiar with protest art. “When I graduated from college that was when Ninoy Aquino was assassinated,” he tells Inquirer Property.

“I’d go to my friend’s house and then his parents had some protest art. I’d go my uncle’s house, he had some protest art,” he disclosed. “I knew that there was protest art. Today, I’m trying to look for them but I can’t find them anymore. I don’t know where they are but they must be in good hands, in the hands of good collectors. You don’t see them at auctions,” Atencio said.

“Protest art, especially anti-Marcos art, I don’t know if it has a wide commercial value. [I don’t know] if there is a demand for anti-Marcos art or for pro-opposition to martial law art. It’s like fried beetles, it’s an acquired taste. It’s not really commercial,” he continued.

For him, protest art is also about nationalism.

“It has a very strong message and the message may not be very politically correct,” said Atencio.

“The problem with protest art is that it’s not very sellable,” he continued. “You don’t want to put a picture of a rally in your living room or in your dining room and take a look at it while you’re eating dinner. It really caters to a very small group of art patrons who actually see that art can be used as a medium for social protests, and then they appreciate that kind of historical value that is painted in canvas or carved in sculpture that now becomes part of some history of the Philippines.”

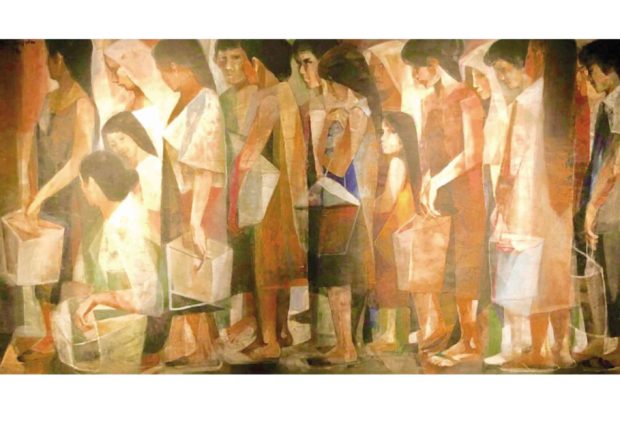

Among Atencio’s extensive art collection are Joven Mansit’s “Uncommon Sense” and “Scene from the Revolution”; “Piano Wings” by Alwin Reamillo; “People Power” by Jose Joya; “People Power” by Onib Olmedo and “Pila sa Bigas” by Vicente Manansala.

“‘Pila sa Bigas’ is a very iconic work by Vicente Manansala and painted in 1978,” described Atencio. It was a a social commentary by the national artist, as one of the effects of martial law was the rice shortage which, incidentally, Atencio also finds appropriate for the country’s current situation.

The art collector regrets how protest art is not as popular as other subject matters of art. He understands, however, that there is also a need for artists to make sure that their art is acceptable to the buying public or somebody who wants to decorate his newly renovated condo and wants a few pieces. “Protest art doesn’t lend itself to that. You don’t want the faces of presidents Marcos and Duterte in your dining room. You want something else, something cheerful, something more standard,” he explained.

“Because its commercial value is weaker, many artists just don’t do it,” he said. “There’s too much risk and very little gain. Nobody really wants to buy protest art and therefore the market is very limited.”

Another concern that Atencio is aware of is the danger of getting into trouble if an artist does a lot of protest art.

For him, however, protest art has to be understood under the bigger context that is nationalism. It is a reminder of the sacrifices of the men and women who came before us and has helped shaped us, as a nation, into what we are today.