Remnants of a dark era

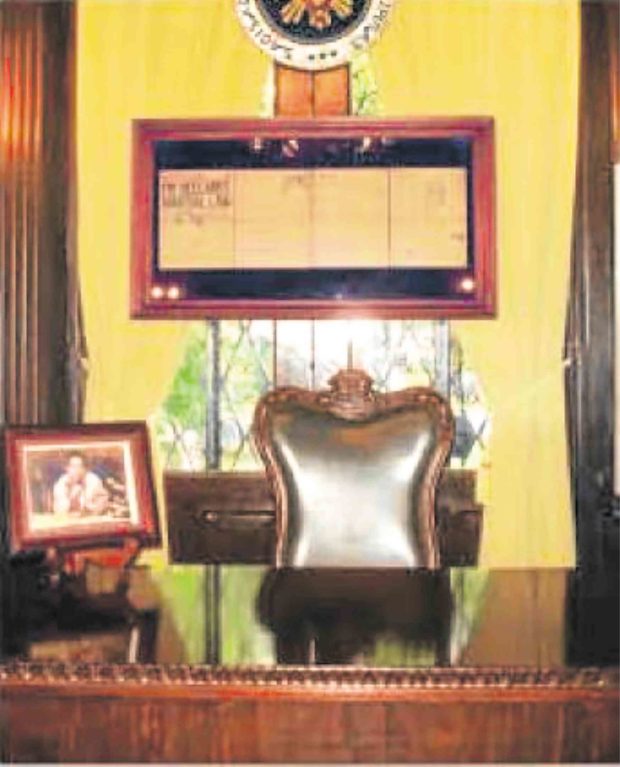

Former President Marcos sat behind a desk at Maharlika Hall in Malacañang where he formally declared martial law.

Within a few hours after Proclamation No. 1081 dated Sept. 21, 1972 was issued, the military had already moved to arrest personalities critical of the Marcos administration.

This period had not only put to test the resolve of Filipinos to fight the dictatorship and restore democracy. It had also tainted, destroyed, or left in ruins key structures, buildings and offices that served as silent witnesses to the abuses during this era.

It can be recalled that former President Ferdinand Marcos went on air to formally announce the declaration of martial law on the night of Sept. 23, 1972. He was sitting behind a desk at Maharlika Hall, the largest room in Kalayaan Hall, which is Malacañang Palace’s oldest building.

But even prior to the formal announcement, the military had already arrested at least 100 of the 400 listed subversives and detained them at Camp Crame gymnasium.

First on the list was opposition senator and main political rival Benigno “Ninoy” Aquino Jr., who was arrested at the Hilton Hotel in Manila on the night of Sept. 22, 1972.

Aquino was in a meeting with the joint congressional committee on tariff reforms with other senators when members of the military, led by Col. Romeo Gatan, asked him to “step outside” the hotel to arrest him.

He was detained at Fort Bonifacio in Taguig City until Mar. 12, 1973 and again on Aug. 27, 1973 until 1980, when he was allowed by Marcos to seek medical treatment in the United States.

Aquino, together with Sen. Jose W. Diokno, was later transferred to Fort Magsaysay in Laur, Nueva Ecija to isolate them from their supporters in Metro Manila, according to military accounts.

Other personalities brought to Camp Crame were former and incumbent Senators Soc Rodrigo, Ramon Mitra and Sergio Osmeña Jr., businessman Eugenio Lopez Jr., teacher Etta Rosales, lawyer Haydee Yorac, journalist Amando Doronila and other prominent Marcos opponents, outspoken journalists, labor union organizers and delegates to the 1971 Constitutional Convention.

Some of them, such as Diokno, were arrested from their residences, while others were nabbed from their work places.

Universities with “subversive links,” such as the University of the Philippines in Diliman, were ordered shut down by Marcos, as youth leaders and teachers were arrested by the military inside the campus.

Also locked down was the Legislative Building. Marcos then abolished the Congress and took over the power to make laws, making himself the one-man Congress despite the opening of the Interim Batasang Pambansa in 1978.

Detention centers were grouped into four regional command for detainees (Recad) under the command for detainees (Cad) in Camp Crame, according to a document acquired by the William S. Richardson School of Law Library at the University of Hawaii at Manoa.

These were the Camp Olivas in Pampanga province (Recad I), Camp Vicente Lim in Laguna province (Recad II), Camp Lapulapu in Cebu province (Recad III) and Camp Evangelista in Cagayan de Oro City (Recad IV).

Inside Camp Crame, detention facilities included the Women’s Detention Center, 5th Constabulary Security Unit and Stockade 4.

Other detainees were sent to the Youth Rehabilitation Center and the Maximum Security Unit in Fort Bonifacio.

In the provinces, there were 80 detention centers during martial law, excluding the “safe houses,” the location of which are unknown.

But while detention centers were being set up to accommodate the political detainees, several infrastructures were built by Marcos supposedly to “assert power and maintain public support,” Gerard Lico writes in his book “Edifice Complex: Power, Myth and Marcos State Architecture.”

The San Juanico bridge, which connects Samar and Leyte provinces, was inaugurated in July 1973 after four years of construction. Also called the “Bridge of Love,” it was purportedly Marcos’ gift to his wife Imelda.

A method of torture was named after the San Juanico bridge, wherein a prisoner was made to lie with his head on one bed and his feet on a second bed, and was beaten and kicked whenever his body sagged or he fell.

At the height of the 1973 energy crisis in the Philippines, Marcos decided to build a 620-megawatt nuclear power plant in Morong town, Bataan province as an alternative source of power to meet the country’s energy demands.

But the nuke plant was never used when its construction was completed in 1984 due to controversies. It was also mothballed by then President Corazon Aquino in 1986 due to safety concerns in the wake of the nuclear fire at the Chernobyl power plant in Russia.

A project of the Marcos administration with its cronies was the P2.5-billion Light Rail Transit Line 1, which today runs from Baclaran in Pasay City to Roosevelt in Quezon City.

A bid for the LRT project was won in 1979 by a consortium of Belgian companies. Construction of the elevated railway transit began in October 1981.

Imelda was known to have a condition called the “edifice complex,” which showed in the construction of buildings at the Cultural Center of the Philippines (CCP) complex when she was CCP chair and health centers dubbed “designer hospitals,” when Imelda was Metro Manila governor and Human Settlements Minister.

The 88-hectare reclaimed CCP complex in Pasay City includes the CCP main building, Folk Arts Theater, Philippine International Convention Center, Manila Film Center and Coconut Palace (also called the “Tahanang Pilipino”).

Sources: Inquirer archives, officialgazette.gov.ph, “The Marcos Regime: Rape of the Nation” by Filemon Rodriguez