Why is rural underemployment so high?

In early 2017, some 6.4 million Filipinos were underemployed, or 16.3 percent of the labor force. Rural regions had high underemployment rates (over 20 percent) such as Bicol, Eastern Visayas, and Soccsksargen, but lower in urbanized regions, i.e.: NCR, 11.9 percent; Davao, 14.6 percent; Calabarzon, 14.8 percent; and Central Luzon, 15.8 percent.

ARMM at 7.3 percent, Negros Island at 11.4 percent, and Zamboanga Peninsula at 15.4 percent had puzzling numbers as they had lower turnout than more advanced regions. Note: Negros has normally peak sugar harvest in January-March.

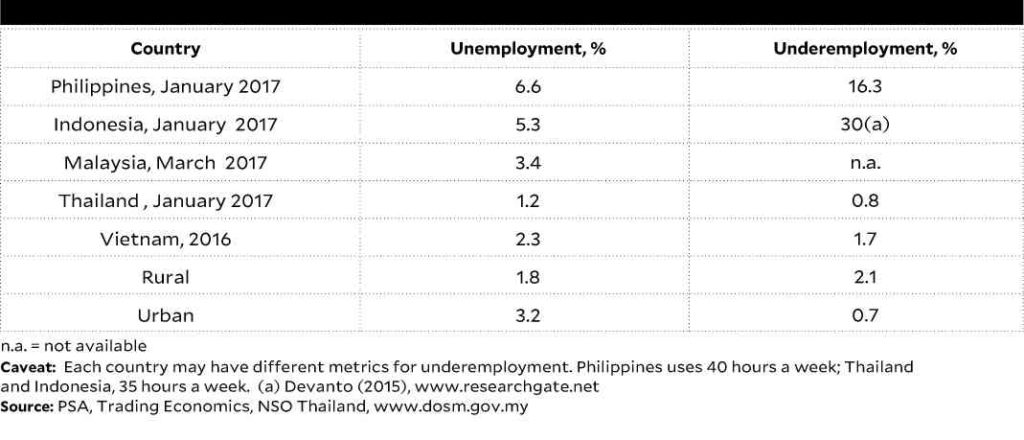

Meanwhile, unemployment is high at 6.6 percent compared to Asean neighbors. By far, Thailand and Vietnam have extremely low unemployment and underemployment rates because of their diversified rural economies. Indonesia, by contrast, has higher figures.

Data show that among the underemployed Filipinos, agriculture workers have the highest depth at 79 percent of working compared to industry, 44 percent, and services, 50 percent.

What factors affect underemployment in the rural sector?

First and well-known, agriculture has high seasonality. For example, irrigated palay and corn have usually two harvests a year. Second, the widespread low farm productivity requires low labor demand. Coconut is harvested only four times a year due to low yield (easily 70 percent below potential). Most of the coconut farms are senile, unfertilized and not intercropped.

But there is also a deeper reason. A farm family can supply two working members. At 250 person-days a year, the total family labor supply will be 500 person-days.

Based on a farm size of one hectare, labor demand for most crops falls short versus family labor, except coconut for coco-sugar, cavendish banana and anthurium. Palay, corn, coconut and sugar have lower employment intensity. Caveat. There is seasonal scarcity of hired labor in some months due to peaking of labor demand during planting and harvest periods.

So where do the underemployed family members go? Many are in the low-skilled services sector, especially in urban areas. Among these are sales workers, domestic helpers and unskilled construction workers. The educated or skilled workers become OFWs.

Can the high rural underemployment be addressed?

Development literature is replete with the role of off-farm employment in reducing poverty. A study conducted in Thailand found that for small farms (less than 2.4 hectares), family members spend 200 person-days a year for off-farm work (Phenilas 1994).

There are ways to reduce rural underemployment, such as by increasing farm productivity and farm diversification. The following actions will induce labor demand:

First, higher farm productivity by higher yields and higher cropping intensity.

Second, crop diversification (coconut intercropping, new products)

Third, productivity plus diversification creates scale for raw materials of processing (agrifood manufacturing) industries for domestic and export markets.

Fourth, cultivation of idle lands.

A Mindanao entrepreneur suggests: Decentralize infra spending to the rural areas including ancillaries, such as electrification, broadband internet and education to draw more activity to the peripheries.

Reliance on few crops will face challenges in lowering rural poverty from 30 percent in 2015 to 20 percent in 2022. This is in the backdrop of increasing mechanization. Moreover, low labor skills and low education deter absorption of farm labor to manufacturing and BPO sectors.

Feedback on my past article (PDI, 10/23/17). Land Bank of the Philippines (LBP) president Alex Buenaventura sent an erratum.

His strategic goal is to triple agrifishery loan portfolio to small farmers and fishers through corporatives from P38 billion in 2016 to P115 billion in 2022, not the total agri lending.