Value of parks, plazas, public open spaces

The front of Bacolod’s new government center integrates the built-up and natural environment. Photos by Ragene Palma

Enrique Peñalosa was then and now the mayor of Bogota, Colombia’s capital, which has a reputation for terrorism, poverty, assassinations, and traffic.

As a leader, he knew how bleak his city was. He also had an underlying philosophy that guided his actions to transform the place into a better city.

He succinctly stated what makes a city brighter, happier, and more livable: “We need to walk, just as birds need to fly. We need to be around other people. We need beauty. We need contact with nature. And most of all, we need not to be excluded. We need to feel some sort of equality.”

Open grounds outside the Jaro Cathedral of Iloilo, along with Jaro Plaza, reflect the heritage, culture, and history of the Ilonggos.

Pedestrians at the fore

Peñalosa emphasized the critical need for public spaces by putting pedestrians at the forefront of planning.

He was almost impeached by elite citizens for removing cars from illegally-made parking spaces and sidewalks.

But he pursued. And to further create better sidewalks, and child-friendly spaces, he campaigned against private encroachment and championed parks and open spaces.

He said: “Parks and other pedestrian places are essential to a city’s happiness… Parks are about many things, but above all parks are about equality.”

Bogota’s once crime-notorious places were transformed into at least 1,200 parks, encouraging interaction and providing more safety to the citizens.

Open spaces serve as a reprieve in the fast-paced, highly-urbanized cities. In land use planning, these spaces are used to create parks and plazas, or simply left or landscaped to remain open and accessible.

Bacolod’s new government center grounds are a happy place, with nightly zumba events, massages, food stalls, and community activities.

Socioeconomic value

In the urban setting, open spaces have socioeconomic value. They are used for a variety of uses, such as recreation (simple walking and biking), relaxation, sports, and holding activities such as family picnics.

Its presence also serves as an aesthetic, a hedonic element, and a health benefit to the populace. Open spaces further become safe spaces for disasters, particularly earthquakes.

All of these increase the quality of life and, in indirect ways, impact the land markets, prices, and real estate’s valuation on the environment.

Pioneer landscape architect and journalist Frederick Law Olmsted, who created the urban park movement and the world-famous Central Park of New York, wrote how public spaces have more value as green spaces: “Foliage and sunlight disinfect the air, while trees provide shade and beauty.”

These “lungs,” as they are called in an urban area, have greater value than we realize.

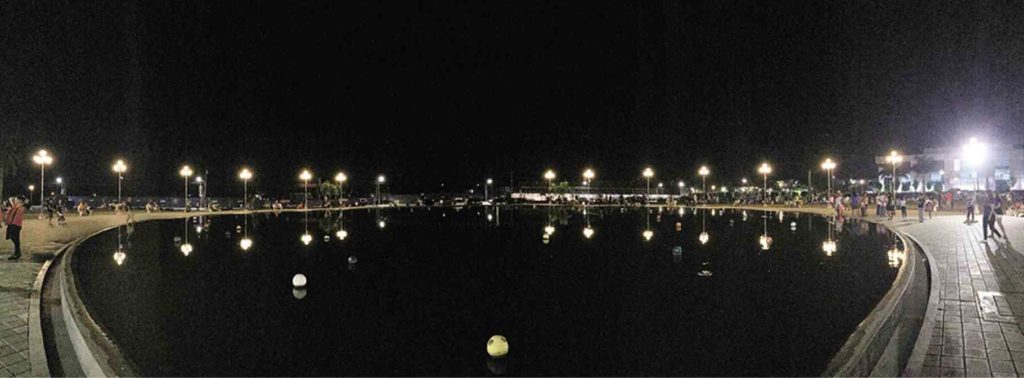

Paseo del Mar is the main park of Zamboanga City. It is used as venue for concerts, Christmas parties, and festival activities.

Improving cities

Olmsted also pointed out how “park systems” can improve cities. Park systems are green spaces connected by walking paths and bicycle lanes. These are a number of small, open grounds that are distributed but well-connected, reachable and walkable from houses.

Parks, plazas, and public, open spaces are a challenge for many developing cities and metropolitans in the sense that their scarcity is pitted against bloating urbanization, or are not preserved because of commercial and private interests.

We should look at open spaces in the vicinities of our work place and homes, and ask these questions: How are we treating them? Are their conditions still favorable to encourage interaction? How much green cover have we left? What have our city leaders done about these spaces? Will they survive in the next decade, and will we see the same green spaces and historical parks?

It will be wise to remember how these spaces play key roles in improving urban centers’ livability and every citizen’s quality of life, and in the long run, in achieving sustainable cities.