Mother Nature gets some corporate love

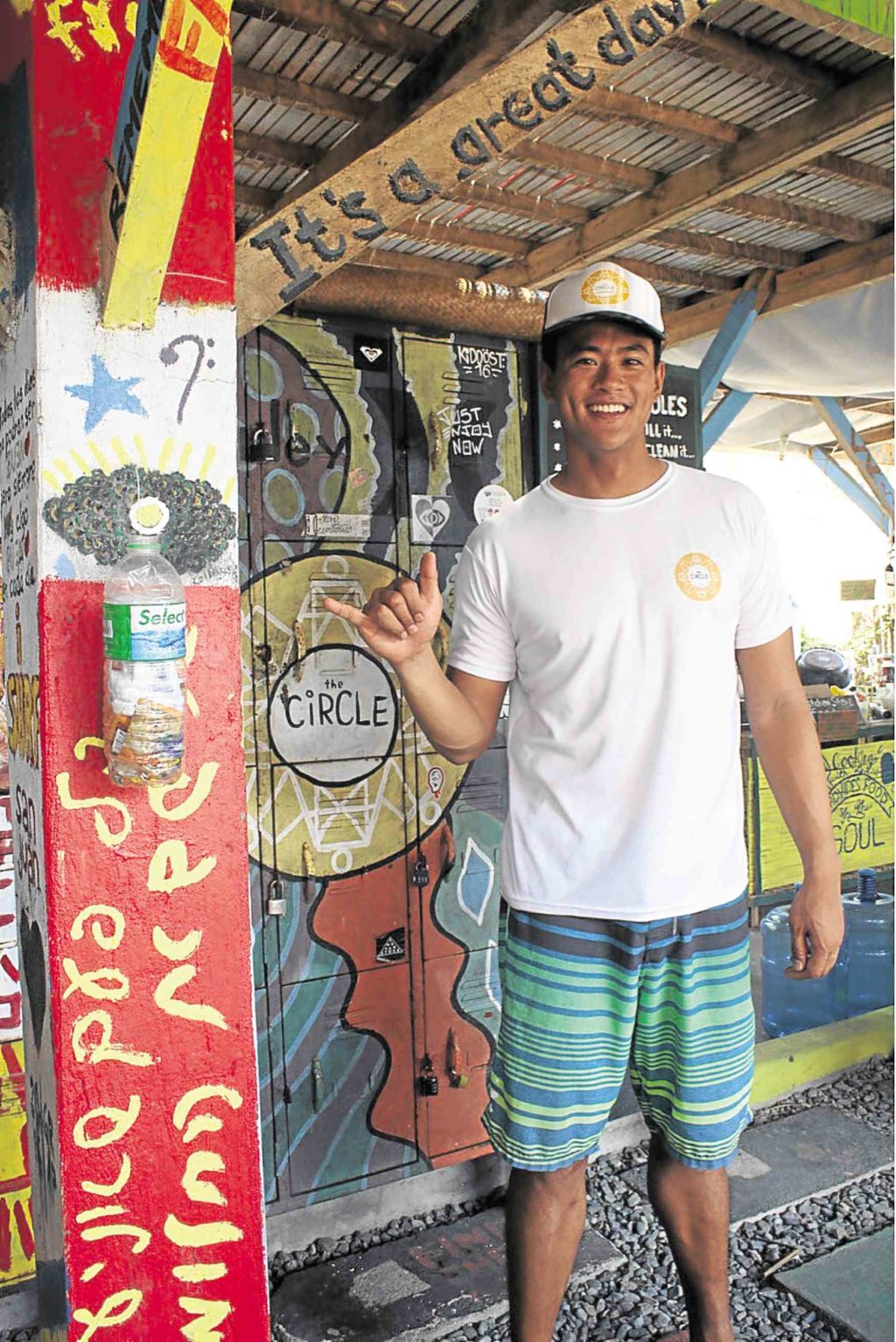

The Circle Hostel’s operations manager Rafael Oca (left) and marketing officer Jerms Choa Peck build a wall using ecobricks —PHOTOS BY ALEC CORPUZ

Hostels, a travel group, and a movement to reduce plastic consumption—what do they have in common?

They’re all run by millennials and social entrepreneurs who are doing everything they can to help preserve Mother Earth.

Born out of love for the sea and, at the time, a lack of affordable beach accommodations, childhood friends Ziggie Gonzales and Raf Dionisio put up Circle Hostel in Zambales in 2011.

Gonzales was inspired by Southeast Asian travels, backpacking through countries such as Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia.

Dionisio, on the other hand, had already been wanting to put up his own business, after leaving his corporate job in a multinational company.

“Circle was my fourth or fifth try [at starting a business], and it was the first one that clicked. I grew up with [Ziggy], and would go camping with him. My first camping trip with him was in Zambales, so it’s kind of serendipitous that we ended up where we started,” says Dionisio, 31, a Management graduate of the Ateneo de Manila University.

Gonzales also went to the same school, where he took up Management Economics.

Prior to putting up the hostel, however, Dionisio had spent some time working for Gawad Kalinga—an experience which opened his eyes to the kind of business he wanted to get into.

“We became very determined to turn Circle into something that’s more than just passion for us, but something very purposeful,” Dionisio says.

That purpose—to be an inclusive business—was fulfilled by Gonzales, Dionisio and their team through two other ventures: Make A Difference (MAD) Travel, which focuses on social tourism, and The Plastic Solution, a campaign to reduce plastic consumption by recycling them as “ecobricks.”

Together with Circle Hostel, MAD Travel organizes “alternative” tours which help both the environment and the communities they visit. One such tour is called Tribes and Treks, a 12-hour day trek through the mountains and rivers of San Felipe, Zambales, where visitors are also taken to an Aeta Village. There they learn about the tribe’s culture and contribute to the tour’s main goal: The reforestation of the community’s rainforest, which has lost most of its trees and plants.

A tour package costs P1,800 and comes with lunch, snacks, and dinner, as well as a carabao ride, archery and herbal medicine classes, dancing, singing, trekking, swimming, and, of course, tree-planting.

Dionisio says they plan to have a similar tour soon in Aurora, where a Circle Hostel branch is also located (there’s one in La Union, too).

“For the tribal families there, one palm tree is equal to one week’s worth of charcoal. So that’s four trees per family per month, and no one’s replanting them. It’s just a matter of time before that all goes to waste, and we want to intervene, start a planting program that’s sustainable and ideally, help them come into other things for livelihood,” Dionisio says.

While MAD Travel answers environmental issues such as deforestation, The Plastic Solution, on the other hand, is Gonzales and Dionisio’s team’s response to the problem of waste.

To make a proper ecobrick, the bottle should be completely stuffed with plastic bits. If you can still squeeze it, it needs more plastic.

“The hostel was originally built out of a lot of wood and bamboo. As we got bigger—the bamboo rots after two to three years—we said, we need something stronger, and also to ensure safety. Instead of building pure cement walls, Ziggie had this idea of using ecobricks, and using that as an alternative to hollow blocks,” says Dionisio.

The “bricks” are plastic bottles stuffed with other pieces of plastic. The idea is for people, instead of just discarding their used plastics, to create these bricks and give them to the Circle Hostel team—either through their Quezon City office or one of their hostels—who then uses them as construction material for small projects.

“The first wall we built was in Baler. It has lasted two or three Category 3 and 4 storms already. The ecobricks are used as a filler to replace hollow blocks; it still has a post, which holds a lot of the structural integrity, and then we replace rebar with bamboo, and then we have a mesh, and the bottles go in the middle, and then you cover it with cement,” explains operations manager Rafael Oca. “So even if the wall falls over, even if it gets damaged, you can still reuse the bottles.”

On the durability, Dionisio further clairifies: “Have ecobricks been tested? In the traditional, ISO, city building setting, no, and we don’t recommend it for that. But if you’re in the countryside and you want a small fence, or, say, park benches, yes, it’s tested. It’ll work.”

Aside from using them for their hostels, the team also sends the ecobricks to schools, companies and other organizations who have expressed interest in making use of the alternative construction material. In Zambales, in fact, Dionisio says they’ll be using the bricks to build a small plant nursery.

While the ecobricks aren’t the group’s original idea, Dionisio says they are happy to be the ones actively pushing it and marketing it here in the country. They’re just glad basically, to do anything that’ll help out the environment.

“If you look at the different generations, basically the older ones kind of messed up the planet and made more plastic. The younger generations are the ones inheriting that Earth, and I’m happy to see a lot of young people becoming more proactive about being environmentally conscious,” Oca says.

“To us, doing good business, which is helping people and the environment, makes good business sense because it’s the only way we’ll be sustainable. I guess it also comes at a time when there’s a renewed sense of nationalism, because more people are falling in love with the Philippines through travel. And when you fall in love with something, and it’s beautiful, you want to protect it. We’re just trying to make it more fun,” adds Dionisio.