The food conquerors: How the Spanish survived their voyage to PH

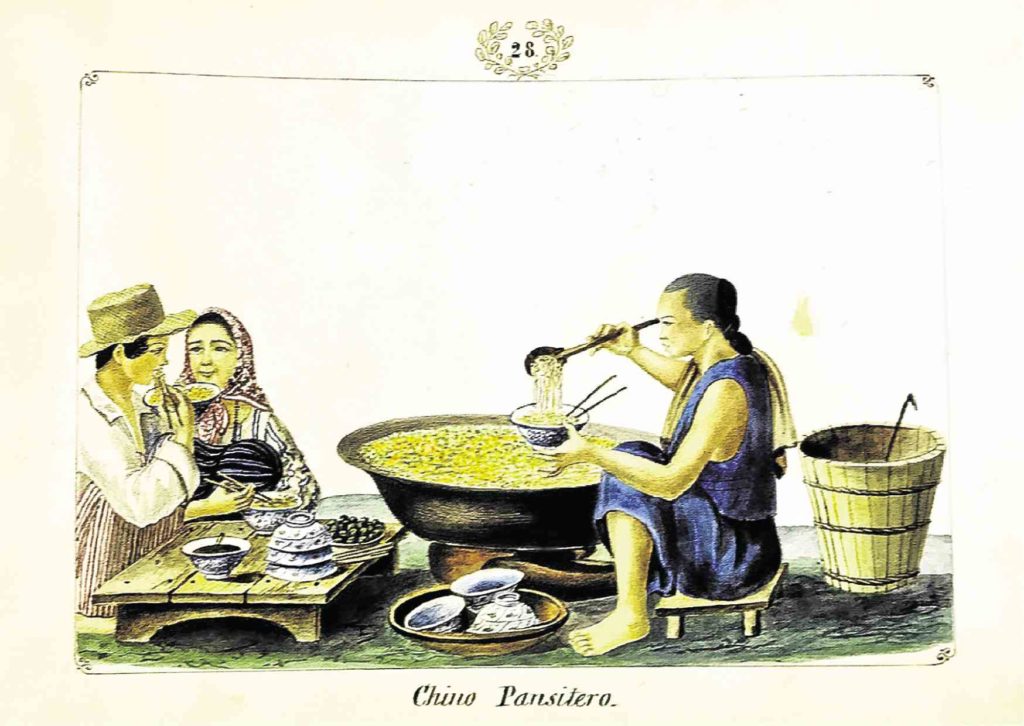

Pen drawing from 1847 of a Chinese pancit vendor from the album Vistas de las Yslas Filipinas by Jose H. Lozano.

If you are keen on taking a break from all the bad news, books are a great escape. I’m finding solace nowadays in books on food history.

I’ve recently escaped into the gastronomic adventures of the 16th century through the sheets of “Flavors that Sail Across the Seas,” a book about Spanish expeditions to Manila written by the head archivist of Seville’s Archivo (Archivo General de Indias), Antonio Sanchez de Mora.

With original official documents from the Spanish government including royal decrees and ship ledgers (as in notes from the boat that Magellan was on) as his source, de Mora painted an exciting picture of what those galleons actually looked like inside by itemizing what they carried.

The original lechon?

I always pictured those galleons to be filled with hundreds of men—sailors and soldiers—like in the movies. According to de Mora, the men actually brought along women to do the cooking (pfft!). The boats also carried live animals and preserved food to feed everyone for months. These galleons were Noah’s Ark—make that arks—on steroids.

Take, for instance, that very first expedition of Ferdinand Magellan that sailed on August 10, 1519. Apparently, there wasn’t just one ship, but five, that completed Magellan’s fleet: the Trinidad (commanded by Magellan), the San Antonio, the Victoria, the Conception and the Santiago. (Of the five, only one successfully went back to Seville, Spain, where they started. It was this ship that proved that the world is round.)

On these boats, too, were seven live cows. And three pigs.

According to this book, these cows and pigs were butchered on board. De Mora, when I interviewed him in Seville last month, explained that this was most likely to make sure that what they ate was not only fresh but edible.

“Remember, there were no refrigerators yet in those days,” de Mora pointed out, although his book noted that Magellan’s expedition did have wood- or coal-fueled copper stoves.

“Repeated mentions of vinegar, oil, lard, and salt suggest the widespread use of preservation techniques,” de Mora wrote. “The cows and pigs brought by Magellan, the rams of the expedition led by Juan de la Isla and the pigs of Legazpi’s (galleon) are to be interpreted in that sense.”

The expedition of Miguel de Legazpi in November 1564 was even more astounding: It carried 44,400 pounds of cecin (dried and smoked cow meat) and 84 live pigs. (That’s a lot of lechon … or bacon!)

There were also other goods on board: 1,977 wheels of cheese; 309 bottles of vinegar; 688 bottles of wine; 250 pounds of white sugar; and 200 pounds of almonds.

They also had sardines, used for baiting. “Fish was an important part of the diet on board … due to the possibility of capturing it during the crossing. … They also carried sardines though they were to be used as bait, which suggests they were fishing large species such as tuna. They were also equipped with fishing gear,” de Mora noted.

Discoveries

Around this time, Europe was already obsessed with spices from the east. King Philip II, in particular, sought all kinds for his sick heir, Prince Don Carlos. De Mora found the original royal decrees (kept in the Archivo General de Indias, Seville) dated October 15, 1567—one to royal officials in Mexico and another to Miguel Lopez de Legazpi—wherein King Philip II ordered that all the cinnamon from the Philippine Islands be sent to Spain. The cinnamon was sourced from Mindanao.

De Mora also noted that Legazpi’s companion and successor, Guido de Lavezaris of the Royal Exchequer “wrote the King alerting that tamarind trees … and ginger roots … for planting would arrive in New Spain from Cebu aboard the San Juan by July 26, 1567.”

Leandro de Viana, a royal fiscal in Manila, also “sent the King bark of calinga … a tree from Mindoro mountains … with a delicious odor, which smells like cinnamon, clove and pepper all combined.” Unfortunately, noted de Mora, this gift was aboard the Santissima Trinidad, which was captured by the British.

In its many other discoveries, the Spaniards tried to reconcile what they found with what they knew.

On tuna: “Lots of tuna, not as large as those of Spain, but of the same make, meat and flavor.” On chicken: “Some are similar to Spanish ones, some indigenous and others very tasty brought from Asian continent.” On avocados, de Mora quoted from Fernandez de Oviedo (1526): “In mainland there are trees that are called perales, but not pear trees such as Spain … the color and shape is true pears, and somewhat thicker crust, but softer, and in the middle has a nugget as a grafted chestnut, peeled; but it is bitter … and between her and the first crust it is what it is eaten, that is fully, and a liquor or paste that is very similar to butter.”

Galleon Trade

In time, the boats became more about commerce than about discovery. By the 1800s, the products on board had become quite sophisticated.

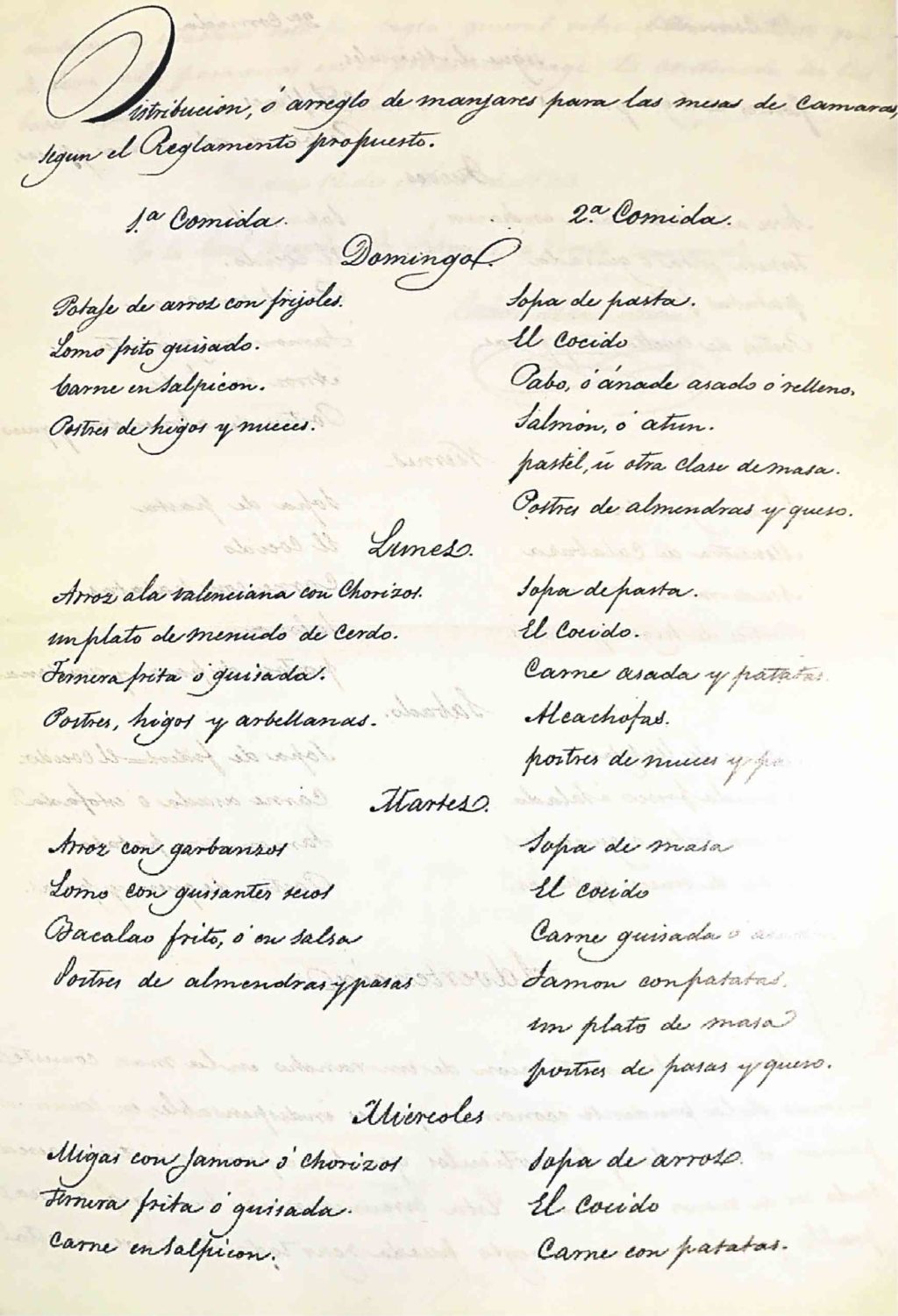

The ship Santa Ana a.k.a. Rey Fernando, which was privately owned by the Company of the Philippines, had a weekly menu in 1833 for the mesas de camara. At noon, the menu included a main course of fried or stewed meats and a first course of rice or beans. Dinner had grilled meats and dessert.

The items on board increased in variety as well. In an 1851 voyage, food was now classified into several headings: “live cattle, their maintenance, meats, fish, vegetables, pickles, beans, wine and vinegar, cheese and desserts, sweets and various items.” And the manuscript that de Mora found showed the following live animals were carried aboard: 10 calves, 30 goats, 30 sheep, 34 pigs, 30 turkeys, 500 chickens, 120 ducks, 40 geese “so they could afford fresh meat and eggs during the voyage.” On top of these, they had preserved meat that included 4,000 pounds (lbs) of beef, 1,056-lbs pork loins, 352-lbs turkeys, 156-lbs rabbits, 120-lbs sausages and 500-lbs animal guts.

Aside from the lady cooks, the ships also carried the cooks of viceroys, governors and archbishops.

Smugglers?

Headlines on smuggling and illegal trading by no less than government officials are apparently nothing new. As far back as 1580, according to documents at the Archivo, one of the first governors of the Philippines, Gonzalo Ronquillo de Peñalosa, was accused of tax evasion and was illegally trading with Peru. While commended for boosting commerce in Manila, creating a Royal Audience for the district of Manila and founding the Alcaiceria (market) of San Fernando, de Mora wrote that de Peñalosa “also wanted to make some personal gain and, as he knew very well about the limitation imposed on the trade with Acapulco, decided to ignore the ban and to freight three galleons to Peru with the pretext of sending artillery.”

Unfortunately for him, traders from Acapulco complained. De Peñalosa was tried in Spanish Court, which culminated in the King reprimanding him and banning any direct communication between the Philippines and Peru.

I guess government scandals are nothing new.

Aside from the momentary escape from today’s brutal world that books provide, I like to read literature like this to understand the roots of our food—to get a perspective on why we eat what we eat by reliving the journey of the flavors that we call our own. It also helps us understand who we are.

“Flavors That Sail Across the Seas” was a project of the Spanish Ministry of Foreign Affairs for an exhibit by the Spanish Embassy in the Philippines also curated by Antonio Sanchez de Mora. The book also contains an essay by renowned Filipino historian Felice Sta. Maria and recipes by chef Chele Gonzalez. De Mora is now working on an exhibit on the Galleon Trade that will hopefully be held in Seville next year.