Shoe, bag designer pays it forward

If there’s one thing that shoe and bag designer Zarah Juan is grateful for in her 10 years of being an entrepreneur, it’s the fact that people who could have been her competitors instead became mentors—and she’s making it a point to pay such kindness forward.

“There was a woman whom I would go to whenever I needed something embroidered, and she taught me everything—where to buy this and that,” says the founder of Greenleaf Eco Bags, one of the first “green” bag brands to make a name for itself in the country. “I asked her, why are you sharing your knowledge, you worked hard for that? And she said, ‘Iha (dear), there’s so much to go around. Hindi mauubos yan. Pero yung mga mananahi tulad natin, nauubos yan. (We won’t run out of knowledge, but we could run out of sewers.) And if I don’t transfer my skills and knowledge, who would? And the only payment she asked for was for me to teach others.”

It was 10 years ago when Juan founded Greenleaf Eco Bags, a venture which started as a mere hobby while she was still working as a flight attendant.

“During my layovers in Japan, I wouldn’t sleep in my hotel room because I would get bored. I loved going to supermarkets, because it’s more practical to bring home food [as pasalubong],” says Juan, a Tourism graduate of the University of Santo Tomas. “I found it so weird that there would always be a section for bags in the supermarket, because back then here in the Philippines, you would only buy food at the supermarket. So I asked my Japanese friend, what are those? Because they weren’t exactly fashionable—just cute canvas bags. And she said, to be honest, you Filipino flight attendants are the only ones who don’t know how these bags are used. These are reusable bags; Japanese don’t use plastic anymore.”

Juan says discovering eco bags was her “eureka moment”; the minute she came home after that trip, she decided to make a couple of her own. After sketching her designs, she then went to Divisoria, bought a couple of canvas bags, and found a sewer and silkscreen printer to help her execute her idea. She would continue to do this every time she spent her days off here in the country, as Juan would routinely give away the bags she made to fellow flight attendants intrigued by the eco bag concept.

A couple of friends then started ordering the bags as souvenirs for family events, says Juan. The first was for a baptism, and the order was merely for 10 pieces; the next, however, was for 100, as they were to be given as wedding souvenirs.

“So my husband, being an entrepreneur also, said, ‘Hey, it looks like you have a following; let’s make a name for your business,’” says Juan. “He coined the name Greenleaf, and registered the business on my behalf since I was still working as a flight attendant at the time.”

What finally pushed Juan to focus on Greenleaf full-time was her biggest break: One of the country’s biggest retail companies found her online (through her listing on the buy-and-sell website OLX, which back then was still called Sulit) and ordered a whopping 4,000 eco bags as souvenirs for the the launch of their real-estate business, which was in two weeks.

“I was dumbfounded. I don’t remember if I was scared or shocked, but when I left their office, I was crying—out of fear,” says Juan, chuckling. By then she had only one sewer, a dressmaker from her hometown Bulacan, under her employment, and two sewing machines in her garage.

“When I came home, I told him, crying, ‘Here we have an order.’ And he goes, ‘Good! Why are you crying?’ And so I said, it’s 4,000. But he was very positive about it. He said, let’s get another sewer here, and then let’s go to Bulacan and outsource the rest of the work there,” Juan says.

Three days after, Juan realized that no matter how hard she and her team tried, they couldn’t meet their client’s demand. Apologizing profusely, she explained the situation to the client—and was relieved to find out that they had purposely ordered a huge number so that they could stock the bags for future events. The real number they needed for the launch was only 500.

“They said, just do your best, and thank you for your honesty. That was, like, Business 101 for me—that it’s better to just be upfront about your limitations,” says Juan, who was able to deliver 2,000 bags after two weeks. Pleased with Juan’s work, her big-time client soon asked her to supply eco bags for their supermarket chain, and also one of their specialty shops selling local items.

As Juan’s business grew, so did her team: She now has around 105 sewers in her factory in Bulacan, and 12 employees in her Makati City office. With their growth came a realization for Juan: Just like the people who helped her achieve the success she has now, she needed to return the favor by teaching others and helping them become entrepreneurs, too.

This she does this through her designer label, Zarah Juan.

“It was also a designer who suggested that I use my own name. I didn’t want it to come off as self-promotion, but he said, no, look at it from a designer’s point of view. Using your name says that you stand by your advocacy, your designs,” she says.

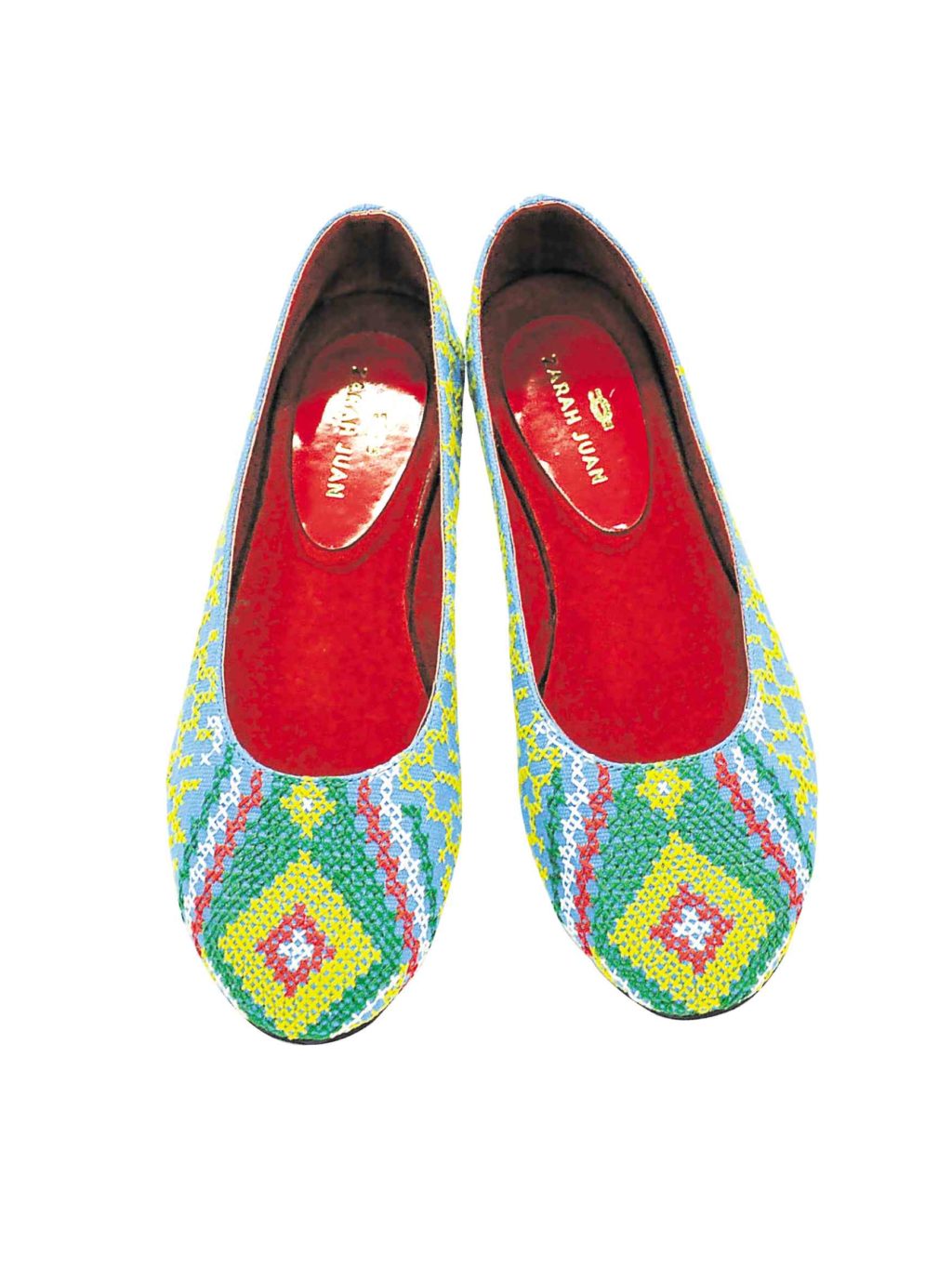

That advocacy can be explicitly seen in Juan’s recent creations: Bags and shoes adorned with beautiful beadwork and weaves by the Bagobo-Tagabawa and T’boli communities with whom she works. Admitting that she “has always been in awe” of tribal communities because of how they represented our true heritage, Juan, in 2013, sought the help of public-private partnership program Great Women, which is spearheaded by Jeannie Javelosa, Chit Juan, and Reena Francisco of Echostore fame.

“Our first product, the beaded espadrille, is a collaboration between my team and the Bagobo. Those shoes gave them livelihood,” Juan says. “What we did was, whatever we learned in production, we applied to the community’s setting. They didn’t have a factory; these people worked at home. We taught them basic things like costing—it’s really a big problem. They would always play it by ear, instead of taking into account the materials they used, the labor. We made a template for them so they could just fill in the blanks: How to do costing, how to make samples, swatching; communications, technology, techniques.”

Her goal, says Juan, is to help these communities become self-sufficient and more professional in their craft, which also makes them less prone to exploitative clients.

“The Bagobo-Tagabawa tribe now has 63 active members who do the beadwork. When we started, there were only 15,” says Juan. “The T’boli has a larger community, and they are impeccable embroiderers and t’nalak weavers. We want them to produce items according to the craft they practice.”

While Juan is pleased to see how far the communities’ products have gone, she says she received her biggest reward when a group of the beaders’ children came up to her and asked if they could also do their parents’ work.

“That was an achievement for me, to know that these crafts can still be passed on to the next generation. So we let them try, but, of course, we also tell them to put their studies first,” she says.

She’s also happy that her passion for design has rubbed off on others, and has helped them see themselves as entrepreneurs as well.

“They say that when you start a business, you should have passion; for me, that’s true. I started by renting a sewing machine for P15 per hour, and then I got a seamstress whom I paid per bag that she sewed. Simple, ” she says. “I just truly enjoyed creating.”