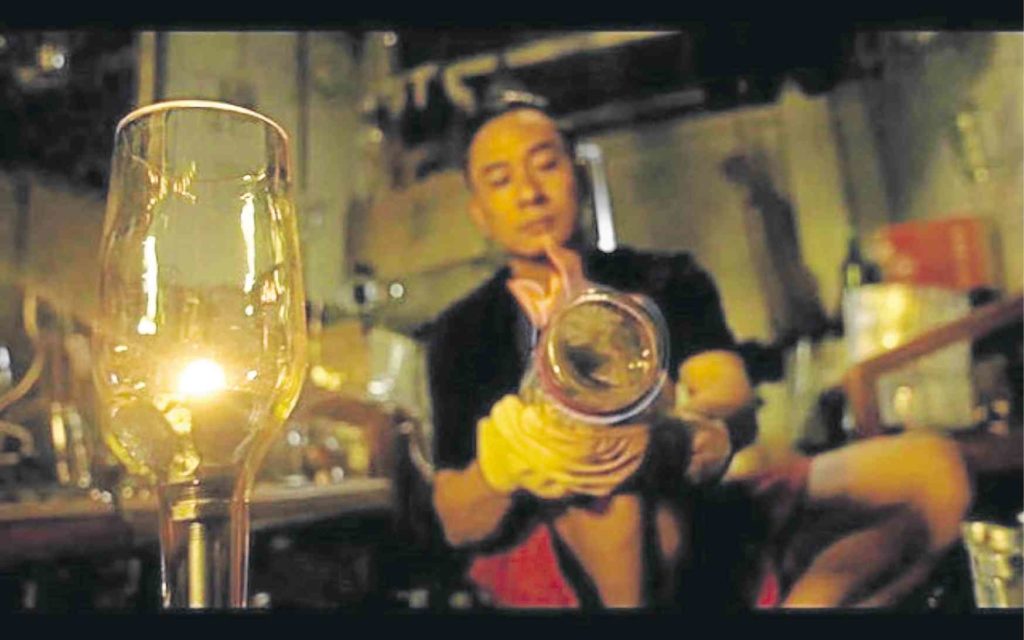

The Vitrum man ‘upcycles’ bottles, jars and glasses to make industrial lighting fixtures.

After cruising the Caribbean and Europe, this diver and environment advocate found his calling right back where he started—at home, in the confines of a 56-square-meter condominium unit, surrounded by empty bottles and electrical wires.

Ian Martinez Sarra is the Vitrum Man, the guy behind the popular Vitrum Bottles and Upcycled Crafts, which makes interesting industrial lighting fixtures from all kinds of bottles, jars and glasses.

Vitrum has gained a following among local celebrities and fans of recycled home décor since it began popping up in bazaars last year.

“It started as a social enterprise, and then we embarked on a crowdfunding project. We were able to raise more than P60,000 in one month,” says Virgilio L. Gutierrez, Sarra’s partner, about The Spark Project, a local crowdfunding platform for creative entrepreneurs, a la Kickstarter.

“Our main agenda in joining The Spark Project was for people to be aware that there’s something like this,” Gutierrez says.

Vitrum has sold more than 100 upcycled bottles

It was Gutierrez’s unfortunate health episode in 2013 that sparked the creative lights in Sarra.

While recovering from a stroke, Gutierrez received bottles of vegetable juices from a friend who owns Detoxify Bar. He was encouraged to consume about seven bottles daily to replace his carbohydrate-loaded diet. He got a week’s worth of bottles, which he hardly touched. Sarra ended up drinking the vegetable juices and cleaning up the bottles.

“There were so many bottles by the end of the week, it was a mess! But they were cute so I didn’t want to throw them away. I did some research on bottles and started doing an art installation detailing my partner’s journey from illness to recovery,” Sarra recalls.

Radio heads

He posted a photo of what he calls his “seven-design installation” using the juice bottles and copper wires on his Facebook page, and began receiving inquiries.

Without any training in the arts, he was both surprised and encouraged. He began experimenting with more art pieces, and later, with lighting fixtures.

“He taught himself to cut glass, to do electrical wiring—he taught himself [how] to do everything just by watching YouTube videos. Twice, he caused a short circuit in the condo because he was trying to see if his lamp bottles would work. Good thing condo units have circuit breakers,” Gutierrez says of Sarra’s first few months working with bottles.

Both avid listeners of local radio stations, Sarra and Gutierrez decided to give one of Sarra’s lamp bottles to deejay Tina Ryan, one of their favorite hosts. Ryan was ecstatic about it and began promoting them to friends. She introduced the couple to her network of bar owners and big drinkers, and soon, they were collecting sacks and sacks of expensive bottles.

“We call her ‘Inday Bote’ because she’s our source of bottles,” Sarra says of Ryan.

“We didn’t really know her. We just followed her on Twitter because we were fans of her radio show. We would always ask for greetings; it keeps us sane in traffic,” Sarra says, laughing. “Now we’re like old friends. She likes to give Vitrum upcycled bottles to her friends as gifts.”

Another deejay who helped the couple when they were starting out was Boom Gonzales. Gonzales was moving out of his condo and did not want to take too many things with him, so he gave Sarra and Gutierrez piles of clothes and accessories, many of them branded and hardly used. Gutierrez and Sarra put up a garage sale and made P20,000, which helped them buy materials for the lighting fixtures.

“He didn’t ask for anything but we gave him a lamp bottle because his mother liked industrial stuff,” Sarra says.

An empty vodka bottle gets a new lease in life

Ship life

Sarra, who studied Hotel and Restaurant Management at the University of Cebu, worked for five years at Costa Cruises, exploring Europe and the Caribbean until 2009, before deciding to stay home for good.

He cited discrimination and despair on board as his reasons for leaving.

“They kept calling me to return for another contract but I wanted to spend Christmas here, so I declined. I learned later that the ship I was supposed to board, Costa Concordia, sank [off the coast of Italy in 2012]. If I had taken that job, I probably wouldn’t be here now. There will be no Vitrum,” he says.

Sarra looked for jobs here but spent most of his time as a volunteer for Greenpeace. As a certified scuba diver, he was active in ocean campaigns. His involvement with Greenpeace introduced him to the concept of upcycling.

“He would work at the terrace of our condo unit, and he often worked at night. He doesn’t sketch; he just examines the materials and works with them. He doesn’t stop until he gets it right,” Gutierrez says of Sarra.

Sarra says he may have gotten his perfectionist streak from his late father.

“My father was a perfectionist. When I was a kid, I remember he made me a scooter from wood, and the cut was just perfect,” Sarra says. “Even with his clothes—he worked in a hotel—my father was particular about looking fine.”

Today, Sarra makes fine things from junk: bottles, GI pipes, broken pedals, vintage helmets, screen doors, discarded wood, etc.

“Good designs don’t come from good bottles. Even if it’s just gin bilog, we can make something of it,” he says. “I make the rounds [in] junk shops on weekends and get all the junk that I can work with. The junk shops in Pasay and Paranaque already know me.”

Gutierrez says they did not see the potential of Sarra’s hobby as a business until last year, when The Artisan Gatherer, a community of makers, sought them out to join a bazaar the group was organizing. The couple was hesitant at first because they did not want to spend on selling Vitrum outside social media.

“It was our first time to join a bazaar. It was Friday-Sunday at Bonifacio High Street. We brought 20 bottles and we were sold out. By Sunday, Ian was creating on the spot because of the demand. That’s when I realized this could be good business,” Gutierrez says.

Vitrum has since sold more than a hundred upcycled bottles. Sarra creates, Gutierrez markets.

“Our vision for Vitrum is first, to have a workshop where Ian can work, because right now, he does everything in our condo, and it can [be] a bit noisy for the neighbors. In a few years, we’d like to have our own physical store. We want people to be able to say, when they want to buy upcycled products, ‘let’s go to Vitrum,’” Gutierrez says.

To date, Vitrum upcycled bottles and crafts are available in five stores: The Craft Central in Greenbelt 5, Common Room in Katipunan, Handcrafted by Harl’s at A. Venue, Resurrection Gallery at 10 Alabama St., and A&G Style Café in Cavite.

As the young enterprise evolves, Sarra would like to be able to tap the out-of-school youth he trained in Daanbantayan in Cebu, his hometown, in creating more products. He trained around 18 high school-age kids in Daanbantayan in 2014, to give them alternative sources of livelihood as they struggled to recover from the devastation caused by typhoon Yolanda.

“For three weeks, I taught them to make lights from bamboo and driftwood. I told them to think of things that inspire them,” Sarra says.

“My plan is to tap the kids who joined my workshop so I can have workers in the company. I don’t want to go into mass production. I’d like to do things slowly, perfectly,” he says.