In another time, and perhaps for another generation, this company’s name—Silya, Elektrika, Atbp.—would have conjured images of pain and punishment.

But today, in an age that values sustainability, Silya, Elektrika, Atbp. is all about giving life to things that have been left for dead.

Silya, Elektrika, Atbp. is a Nueva Vizcaya-based company that collects scrap materials from demolition and construction sites, and turns them into unique pieces of lighting and furniture that are straight out of Pinterest.

“People sell us old structures to be demolished to make way for new ones. In the province, where we’re from, they don’t want wooden houses anymore; they want cement, so they just sell us their wood,” says Gariel Peros, the 26-year-old owner and manager of Silya, Elektrika, atbp.

On good days, Peros gets an entire house for P20,000.

“Most of the time, what we still find useful are the floors, stairs and pillars. These are usually made of teak wood, molave, narra. Most floors are narra,” she says. “Some houses also have Capiz windows.”

Peros hails from Aritao, an onion-growing town in Nueva Vizcaya where her parents, both architects, used to have a pottery business.

The Department of Trade and Industry (DTI) had showcased their products for its One Town, One Product campaign, even in trade fairs abroad.

That pottery business has since closed, and the young entrepreneur’s parents now run a construction company.

By her observation, Peros says 20-30 percent of construction materials, mostly wood and metal, end up as scrap, which is such a waste.

In her hometown, contractors often use gmelina for frames instead of the usual coco lumber found in many Metro Manila construction sites.

“Gmelina is cheaper than coco lumber because we have a lot of hardwood. Instead of throwing out those scrap wood or dumping them in junk shops, we just use them to make furniture,” Peros says.

Peros’ father, Guillermo, a muti-talented artist who paints, sculpts, and builds houses, was the first to broach the idea of using scrap wood for furniture, as many of his clients would often ask him to also build them a dining set.

Back then, in 2009, Peros was fresh out of college and tried to pursue the usual path: after finishing an information technology course at St. Mary’s University in Bayombong, she went to Manila to work at a BPO. She lasted all of one year.

“I really was not cut out for that. I did not like being stuck in an office. I wanted adventure. I wanted to discover myself, to discover new things. If you’re in an office, it’s the same thing every day; it becomes a cycle,” says Peros, echoing a common sentiment among millennials.

Peros quit and went back to the province. She got involved in her family’s construction business as project manager.

In 2015, she heeded her father’s advice to try her hand at business.

She put up Silya, Elektrika, Atbp. as an independent furniture enterprise.

“We named it Silya, Elektrika because we started with stools and then we added lighting fixtures for Manila FAME,” Peros says.

Like her father, she was interested in the arts, particularly graphic design, and it showed in Silya, Elektrika, Atbp.’s early pieces.

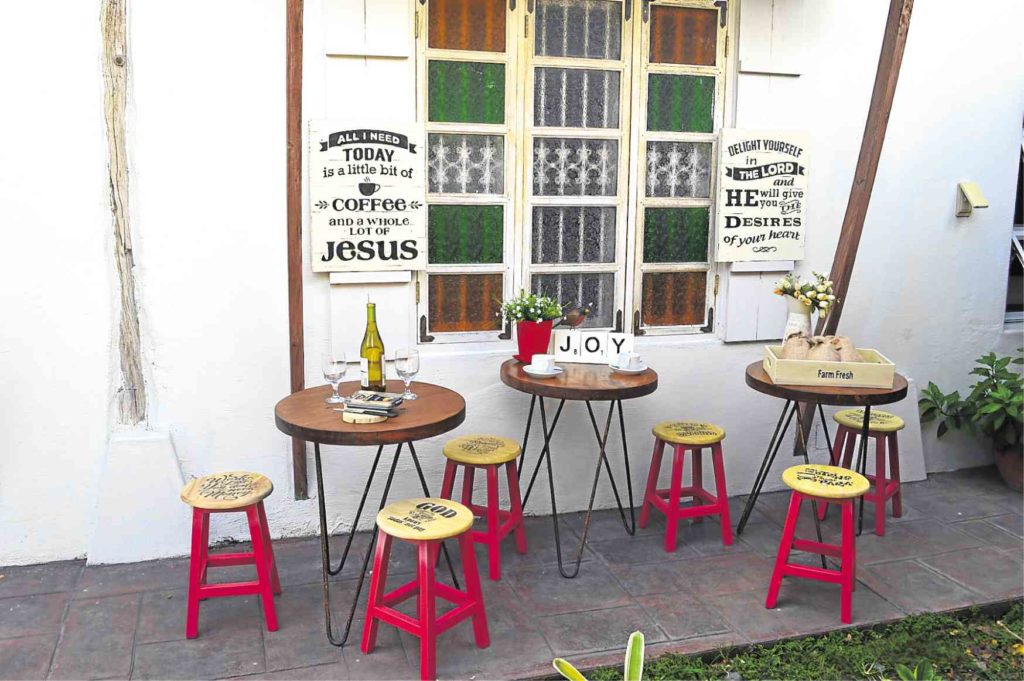

“At first, it was more wall art and calligraphy. We used quotes, words of wisdom, Bible verses,” Peros says, noting how the company was known for its wooden scrabble letter tiles and Filipino sayings.

The DTI, which strives to promote regional businesses, supported the Aritao-based enterprise by sending designers from the Design Center of the Philippines to craft culturally inspired furniture pieces, such as the alibata stools.

The company also gets design help from family friends, designer Manolet Africa and painter Oly Sese.

Local carpenters and artisans, who were trained by Peros’ father, would execute these designs.

It was a little difficult for the carpenters at first, Peros says, because they were not used to repurposing wood, but eventually, they learned to work fast using only photos as reference.

“Now, we can make 50 products a month, most of them tables,” Peros says. “There really is a market for these things. We didn’t know it would be profitable until we joined fairs. Our first fair was Manila FAME in 2015 at SMX. We’ve done Manila FAME thrice by now, thanks to DTI.”

In all three events, Silya, Elektrika, Atbp. brought its popular items like hairpin stools, scrabble tiles, chandeliers, console tables, lamps and wall art.

“We’re sold out by the end of Manila FAME, and the rest are already orders,” says Peros. “We could not have a pop-up store like we always wanted because the products are bought quickly and there’s no space in our garage to store many large pieces.”

Because of the network they built at Manila FAME, the company now supplies furniture to as far as Cagayan de Oro, where their pieces are carried by Home and Country store.

“The owner of Home and Country loves the theme of Mary Grace Café, which is a lot like what we do, so she ordered a lot from us. She shoulders the shipping fee from Nueva Vizacaya to Cagayan de Oro,” Peros says.

In December 2016, the company joined the National Arts and Crafts Fair at the Mega Fashion Hall at SM Megamall in Mandaluyong Cty. They won as best-dressed booth at the event.

Peros says joining fairs inspires her as an entrepreneur because she sees how good the other artists are, and how polished their work is.

Even if Silya, Elektrika Atbp’s design aesthetic leans towards vintage industrial, it must be done very well and with attention to detail, she points out.

“The tough part about the industrial look is achieving different finishes. You have to play with the wood and metal. About 60 percent of products are from reclaimed wood and scrap wood,” Peros says.

“What we want is one design per item but it’s hard because you see a lot of copies, and some people also request the same design we’ve already made,” she says.

While the market in Metro Manila is seeing more offerings of reclaimed wood products, Peros says she is not really conscious of the competition. The business is more like a hobby for her.

“We do it more for fun. As long as our client is happy and satisfied, we’re okay,” she says.

One of her toughest orders so far was from a Japanese client who wanted a map of the United States carved out of wood – all the states, and they must fit together like a puzzle.

“That was really hard because some pieces of wood would shrink, but we managed to do it, all 51 pieces cut and embossed. The client ordered a lot more from us,” she says.

Happy clients allow Silya, Elektrika, Atbp. to salvage the soul of more old houses and breathe life into old wood.

“Many old houses just end up as firewood. We’re happy because we can turn some of them into something else—something that people can appreciate in their own homes,” Peros says. —CONTRIBUTED