Home of independence

The Aguinaldo Shrine is now both a national shrine and a museum maintained by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines.

The ancestral house and birthplace of Emilio Aguinaldo, the first Philippine president, is an important piece of history. It is where the country’s independence from Spain was proclaimed, and where the national flag was waved with the national anthem on the background on June 12, 1898.

But Philippine independence was actually declared from a front window of the grand hall and not from the “Independence Balcony,” which the Aguinaldo house is best known for.

Commemoration and reenactments of Philippine independence in recent years have been focused largely on the famous balcony, a feature that was not built until the 1920s, when the original structure was then expanded.

172-year-old mansion

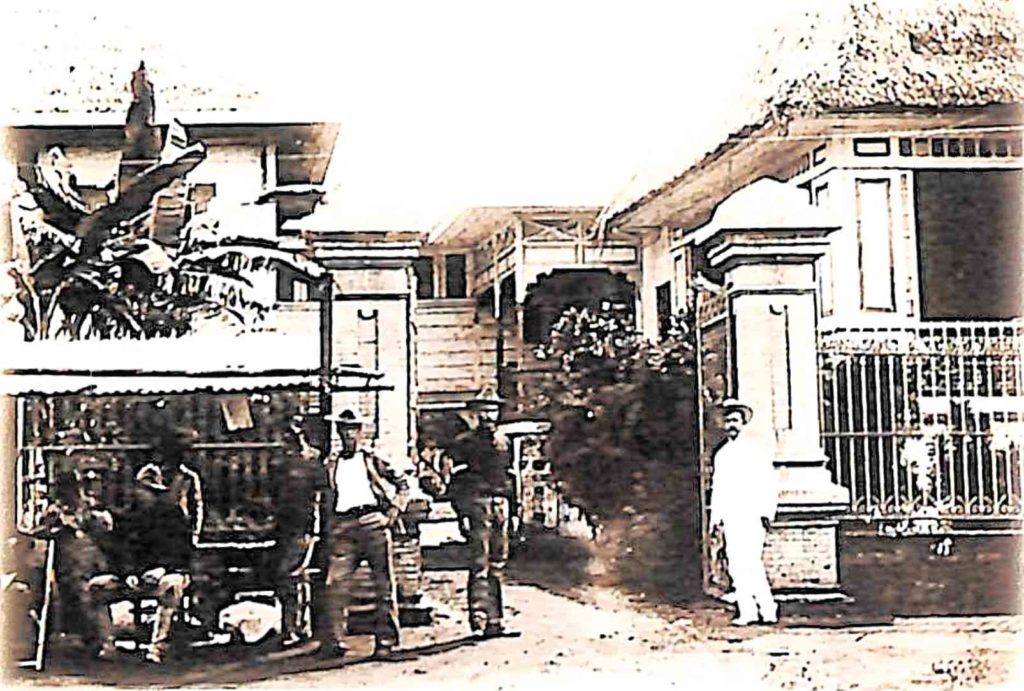

The house was first constructed by Aguinaldo’s parents in 1845 as a humble nipa-and-wood structure—far from the Aguinaldo Shrine we know today. Several renovations in 1849 and again from 1919 to 1925 made the Aguinaldo house a mansion with influences from Malayan, Baroque and Romanesque architecture.

The Aguinaldo Shrine has a floor area of over 1,300 sqm and is divided into three areas—the main house, a lookout tower and the family wing—on a 4,864 sqm lot. It has seven levels, counting the mezzanine and turret.

The 172-year-old mansion sits on Camino Real, the town’s most important road at the center of Kawit, suggesting that the Aguinaldo family belonged to the principalía, the ruling class of colonial times.

Upon entering the living room, you would be greeted with Art Nouveau embellishments, fine furniture, lunette mirrors, wood carvings, oil paintings and up on the ceiling, the seven-meter-long Philippine map in painted wood relief.

Secret passages can be found in the house including those in the hero’s bedroom—one of the floorboards lead to a private one-lane, duckpin bowling alley and an adjoining swimming pool.

In other parts of the house, cabinets can be turned to reveal a hidden passage.

The heavy granite kitchen table hides a hole that supposedly served as an air-raid shelter under the house, while one of the holes in the kitchen floor lead to a long tunnel (or tunnels) that end up either in the church of Kawit or the parish cemetery. There was also a dangling rope that served as a means of escape for Aguinaldo.

Knowing Aguinaldo

Giving us a glimpse of who Aguinaldo was are the memorabilia on display which include the former general’s uniform, his boots, rusty sabers, outdated guns, insignia, and even the huge, smooth rock that he supposedly sat on after his long trek from Malolos, Bulacan to Palanan, Isabela, where the Americans eventually caught up with him.

One can find in his medicine cabinet small bottles containing the relics of Aguinaldo’s appendectomy—a gauze and his pickled appendix.

Displayed outside was his 1924 Packard limousine and in the garden was his marble tomb, guarded by men of the Armed Forces of the Philippines day and night.

During the celebration of Independence Day in 1963, Aguinaldo was said to have donated the mansion and the lot to the Philippine government “to perpetuate the spirit of the Philippine Revolution of 1896 that put an end to Spanish colonization of the country.”

This was about eight months before his death in February 1964.

On June 18, 1964, President Diosdado Macapagal declared the mansion a national shrine by virtue of Republic Act No. 4039.

Shrine and museum

The Aguinaldo Shrine today is both a national shrine and a museum maintained by the National Historical Commission of the Philippines. And every year, government officials visit the mansion to raise the Philippine flag and look back at the time when the Philippines was finally freed from the Spanish conquerors.

The number of spectators who come to witness the flag-raising ceremony at the balcony reach as many as 3,000 each year. On ordinary days, about 375 guests a day visit the site.

As historian Ambeth Ocampo once put it, the Aguinaldo’s house is a house of memory and it is so designed to make Filipinos remember.