Cesar F. Legaspi is one National Artist whose immense talent knows few bounds.

Aside from being credited for “refining cubism in the Philippine context” and a pioneer neo-realist, Legaspi, with his trademark geometric fragmentation technique, also put his stamp on the hypercompetitive advertising world.

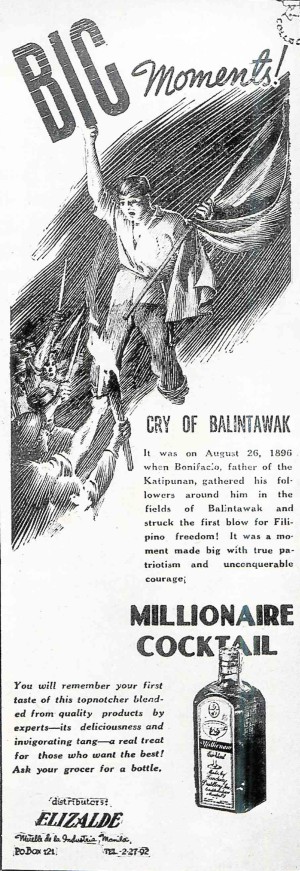

According to his granddaughter Waya Gallardo, Legaspi started working in advertising in 1936 as a staff artist at the advertising department of Elizalde and Co., one of the largest conglomerates at that time.

Legaspi had not even graduated yet from his commercial arts course at the University of the Philippines, but was already approached by a UP alumnus who was leaving the company. He asked the young Legaspi if he wanted to take his place, and he did.

Legaspi worked under Pete Teodoro and started with a salary of just P50 a month.

“My job was staff artist of Elizalde’s advertising department under Pete Teodoro. Elizalde & Company carried diverse products: From wine to rope, from life insurance to a steamship company. I was the only artist there, so I had to do all the illustrations for these various products,” Legaspi was quoted as saying in “The Making of a National Artist” by Alfredo Roces.

Advertising proved to be a good fit, Gallardo says.

“His colorblindness wasn’t an issue, as all print ads were done in black and white, though he had to come up with distinct designs for each product on his own, learning along the way,” she says.

Most of his work was done with pen and ink, though sometimes he would use other materials like white ink, tempera, showcard, charcoal without smudging to avoid half-tone, as print media at the time wasn’t equipped to handle it.

During the war, Legaspi continued to work at Elizalde and Co., albeit at a reduced salary of P18 a month. Thereafter, Elizalde and Co.’s advertising department folded.

Fortunately, Legaspi’s old boss had formed Philprom and he was immediately hired as staff artist for the new agency.

Legaspi climbed the ranks to art director, and later became vice president of creative planning. He was also made vice president and then president of the Art Director’s Club.

Gallardo says that all throughout his time in the advertising world, Legaspi always found time to paint, on weekends and after work. But eventually, he gave up advertising to concentrate fully on his art.

Legaspi’s decision was also prompted by the success of the three-man show featuring him, Hernando Ocampo and Arturo Luz. He started getting more commissions than he could handle given his limited time, when he was juggling both advertising and painting.

When Legaspi, one of the leading lights of modern art in the Philippines finally quit, it was 1968, and Legaspi had been in advertising for over 30 years.

“Later on, Lolo would acknowledge that advertising was very hard for him, that you had to love it to do it. But he always credited his advertising days for instilling in him an incredible work ethic. He worked 8 to 9 hours a day in his studio, with breaks for meals; you could practically set your watch by him, he always kept very regular, disciplined hours, as if he still had a 9-to-5 job. And the fact that he was thrown into work and had to learn things on his feet proved valuable training as well, as Lolo always pushed himself to experiment and educate himself continuously, even when he was already National Artist and well into his 70s,” Gallardo says.

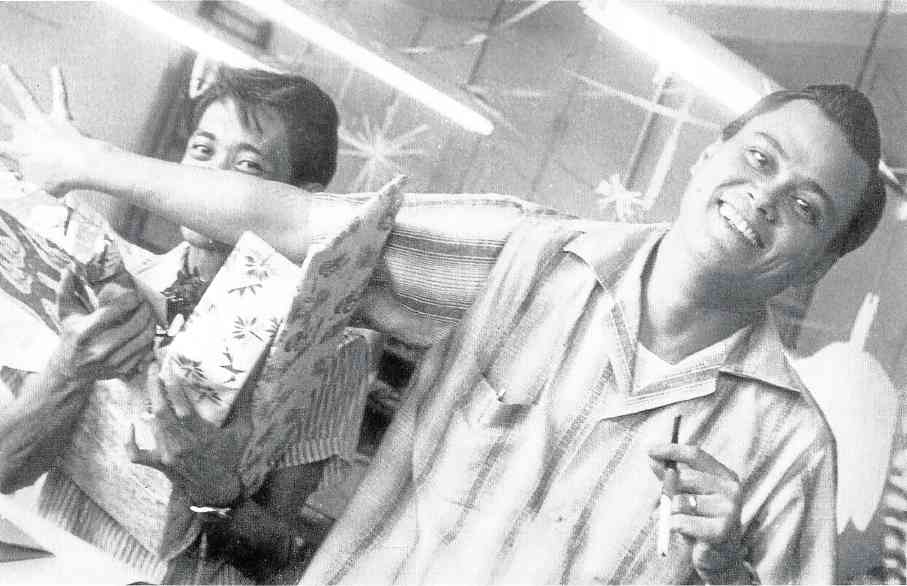

“… Cesar was something of a dandy: A handsome top advertising executive with sharply chiseled mestizo features, brandishing a long black cigarette holder, pomaded hair parted and well combed, sporting a colored sports shirt and white trousers, black and white Florsheim shoes-the very model of the Manila sophisticate,” (Legaspi, The Making of a National Artist, Alfredo Roces).

(Ongoing at the Cultural Center of the Philippines is Lying in State, an exhibit of some of the most important works of the National Artist. The exhibit, which will run until June 4 this year, is the first in a series of events celebrating Legaspi’s birth centennial.)