‘The tree of hope’ offers good, stable income

Photos by Juan Escandor Jr., Inquirer Southern Luzon

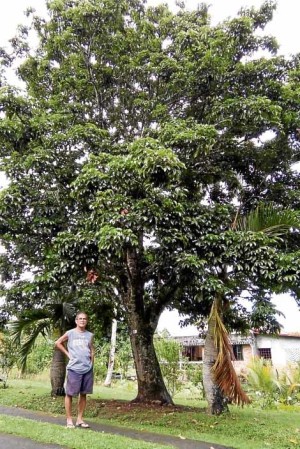

SORSOGON CITY— Branded by the Department of Agriculture “the tree of hope,” pili (Canarium ovatum) has brought good life and comfort to the family of a former mechanic who pioneered in grafted pili tree growing 29 years ago.

Jose Amador, now 74, said he had made the best decision in life in 1976 when he quit his old job and started putting to use his family’s 12-hectare property in the village of Guinlajon, five kilometers from the city proper.

Amador left his job as a mechanic to become a full-time farmer. He started with planting kalamansi (Citrofurtonella micropa) using grafted seedlings.

After more than a decade, however, his harvest started to decline so he thought of venturing into another crop, and that was when he decided to try pili.

In 1987, he started the pili plantation using grafted pili seedlings without much expectation. The pili trees started bearing fruits five years later.

More productive

Amador said with the pili plantation, he was able to send his two children to college—his son became a doctor and is now living in the United States, while his daughter, a registered nurse, works in Metro Manila.

“What’s good with pili is that when it gets older, it bears more fruits,” he said.

Amador said his grafted pili plantation debunked the notion that grafted trees had shorter life. “It is not true with pili,” he said.

He added that in his plantation he cut down the male pili trees because they got bigger but unproductive and kept the female trees which continuously bear fruit.

At present, he harvests 5 to 10 tons of pili nuts a year. Amador’s pili produce sells at an average of P55 per kilo. “But the price sometimes peaks at P90/kilo.”

If prices go below P50 a kilo, Amador opts to stock the nuts and wait until prices go up again.

Amador said pili trees were sturdy as they are deeply rooted and they withstand even strong typhoons. This is an important consideration particularly in typhoon-prone areas like Sorsogon.

“When Typhoon Glenda hit Sorsogon two years ago, it took only a month for the pili trees to recover. In fact, after the typhoon, the pili trees looked like they were just pruned,” he said.

A month after the typhoon, the leaves and the flowers started coming out again.

Purely organic

Amador said his pili trees were purely organic that they did not need any fertilizer to make them productive the whole year round. Even without weeding, they continue to bear fruits, he added.

He hires only four laborers to take care of the pili plantation but he taps additional farm hands for harvesting and post-harvest work like drying the pili nuts.

Because 68 percent of the pili fruit is pulp, Amador realized it could be processed for added value. He attended a training program offered by the Department of Science and Technology and learned how to extract oil from it.

After soaking the pili fruit in water to soften the pulp, the nuts are taken out, he said describing the process of extracting pili oil. The pulp is placed in a cheese cloth and squeezed in a contraption to extract the liquid which is stocked in pails.

Overnight, the oil floats on the surface and is scooped with a ladle or dipper, transferred to another container, and cooked for a maximum of one hour or until all the water have evaporated.

Adding value

Amador said the extraction of oil from the pili pulp was very primitive and labor-intensive which required technology research and improvement.

He said the pulp of 1,000 pili fruits could make one to two liters of oil. He said the output could be higher if the technology and process of extraction were more efficient. At present, he gets P100 for a liter of the raw pili oil.

What is left of the extracted pulp is dried and turned into powder which he mixes with feeds for cattle.

Amador, who pioneered grafted pili growing in the country, was named Tofarm (The Outstanding Farmers of the Philippines) Farmer of the Year in 2014.