SMEs urged to buy students’ technologies, innovations

INNOVATION is like love: Everyone wants it, but no one can accurately define it; and everyone who thinks they have it, definitely wants more of it.

Small and medium enterprises (SMEs) desperately need innovation.

The perpetual struggle of a Filipino SME is to build a scalable business that can expand into new markets despite the entry of new players on the heels of the Association of Southeast Asian Nation (Asean) integration. Unlocking high-value innovations in the least costly way possible is a must if we are to build a solid foundation for our economy and provide jobs in every region and for every skill level.

The best way to do that is to partner with organizations that already do the research—our universities. Universities are not just sources of employees, they have untapped wells of good research that can be developed to fit market needs and then built into new products.

Let the scientists and engineers do the heavy lifting of technology development. An SME, in the end, can contribute what it knows best: figuring out what customers really want and selling that solution.

Resulting innovations that come out of universities will be protected by patents that create a monopoly for any SME—no local or foreign firm can manufacture, sell, or even import anything similar for 20 years.

Partnership strategies

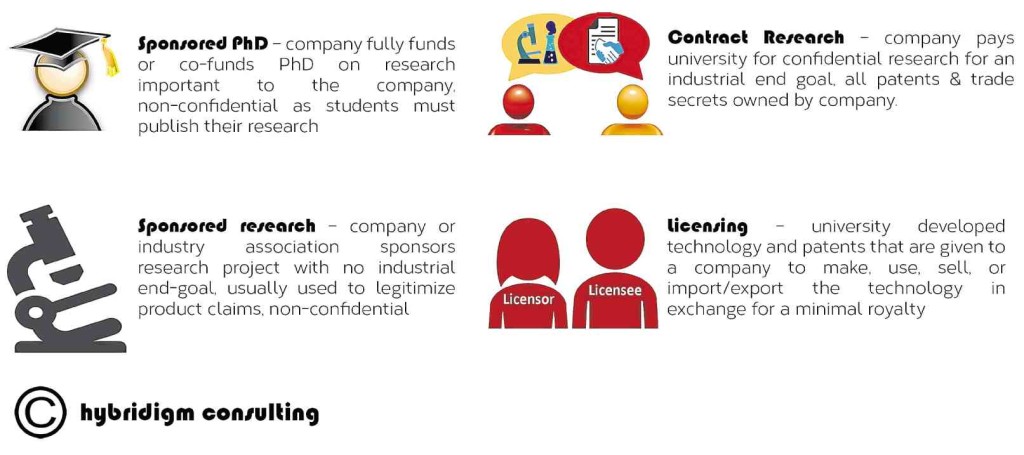

The most affordable way for a small company is to sponsor a graduate student. SME owners can talk to a university admin about what customer problems they want to address, work with faculty to craft a research project, then simply sponsor the tuition of a deserving MS or PhD student.

When students graduate and publish their research, an SME can always cite their work in product literature. It’s also possible to work out a deal with the university for an SME to own the patent or share revenue from royalties. Many companies in Europe and the US take this route.

Working together as an industry association can also lower costs for innovation. The Chamber of Herbal Industries could sponsor a research or clinical trial to determine the use of a particular plant, say the “tawa-tawa (Euphorbia hirta),” and come out with a therapeutic claim for a whole class of products that could be sold throughout the Asean region to treat dengue.

Medium-sized firms with some cash can invest in contract research by telling universities to develop the product they want—in secret from all their competitors—and owning the know-how, the patent and the brand completely. Simple products like shampoo or solar-powered smartphone charging docks will only take a couple of months, while complex systems like a supply chain management system tailored specifically to an SME might require a couple of years. This strategy is cheaper compared to building, maintaining, and staffing an R&D unit.

SMEs should also remember to reach out to the fine arts department for logo design and the business school for market testing. Students can learning something from this and boost their CV or portfolio, while the company, meanwhile, can get good value at a fraction of the cost.

Licensing a university technology is an option that provides the best value for money. Most universities have a portfolio of potential innovations, but have no one to partner with who can take it to market.

Affordable but not free

SMEs are stunned they still have to pay for these services. They reason that the taxes they paid should already fund, through a government grant, the research the universities will conduct.

Why pay a second time? Research isn’t technology in the same way that leather isn’t shoes.

By paying an upfront fee and royalty that could be based on a minimal percentage of sales, an SME enables the university to maintain their scientific equipment as well as the scientist to hire more research assistants so they can do even more work. It also gives our best engineers and scientists a reason to stay in the country, building a critical mass that may foster the birth of the next Dropbox, AirBnB, Pfizer, or Shell.

The best thing about innovation is that it’s distinctly possible to earn large amounts of money while helping the country.

Which university?

There are several factors to consider when selecting a university partner. Research is the precursor of any good technology, just as the quality of ingredients is the foundation of any good dish.

The number of reputable publications per university is the first metric. Scientists who publish their research in academic journals have to go through American Idol levels of vetting by their peers in the field. The second metric is how large of an impact this research has—this is measured by how many of their peers have read and cited their work in other research.

Then there are the technology metrics. We look at the number of patents that are still within the 20-year monopoly time limit, and how many of these patents were licensed by the private sector.

We also track the revenue from all technology-related IP (including software code, which is protected by copyright, and brands, which are protected by trademarks) as well as the revenue from university patents. It’s important to look at deal flow because intellectual property is the same as physical property. Note that it’s very expensive to own and maintain a condo if no one wants to rent it.

These metrics are indicators of how relevant a university’s applied research and technology are to Filipino businesses.

We compare the six major universities that have already started promoting national competitiveness by transferring their technology to the private sector: University of the Philippines in Diliman, Manila, and Los Baños, which all began efforts in 1997; University of Santo Tomas (2009); and the University of San Carlos (2011).

In general, partnering with any of the UP campuses is like heading to a food court. They have the largest variety and selection options in medicine, agriculture, software, hardware and engineering.

Private universities such as UST and USC tend to focus their research on specific industries. Partnering with them is like eating at a restaurant, they have specific cuisine and table-side service.

The UP system’s problem is not in the quality of its technology, although some are not as market-relevant as one would hope. Diliman and Manila produce high quality research above the global average, but have not been as effective at transforming it to actual solutions for Filipinos. UPLB’s research is below the global average, but has been able to create a social impact.

SMEs, however, will have to face bureaucracy and red tape in UP since the state university is bound by government policies and regulations. Private universities do not have that kind of issue and are able to provide better service.

USC’s BioProcess Engineering Research Center is a separate business unit of the university that operates at the same speed as business. SMEs will speak to only one person with the mandate, authority, and flexibility to structure deals quickly.

UP has had several successes under its belt over the last 30 years despite its long transaction times: UPLB’s Bio-N biofertilizer that has netted P47 million in revenues (although the government is still the primary purchaser) and UP Manila’s lagundi technology, which has earned P20 million by licensing the formulation to both SMEs and larger local companies.

USC has a similar global research impact as UPLB, but its focus has paid off thanks to its partnerships with local Cebuano businesses. USC has done 12 contract research projects for industry, developed 10 products exclusively for SMEs and launched 2 startups based on its own technology.

One of these startups is Green Enviro Management Systems, the first mango waste bio-refinery in the world, which has garnered over P200 million in investments to date. Within a month of launching the bio-refinery, the startup already had purchase orders from South Africa for the mango flour, tea, and oils extracted from mango seed and mango peel. Literally, it’s money from garbage.

USC’s hit rate for providing value to businesses is 38 percent, which is above the 30 percent average achieved by American universities.

Ultimately, if an SME can afford to invest time and money for high tech products, building a relationship with UP will be worth it. If an SME needs something that can be tailored to its needs in a short time frame, partnering with a private university like UST or USC is a must.

Maoi Arroyo and John Orlina are the CEO and COO, respectively, of Hybridigm Consulting. The firm helped commercialize Filipino innovations in the last 12 years and created 3,500 jobs in the Philippines through inclusive innovations.