SINGAPORE — For the eight years that he courted Ms. Lim Seou Lan until he married her in 1995, Jason Yeo was neither a doting nor indulgent boyfriend.

He was working 21 hours a day trying to keep his automation business afloat, and way too poor to afford her anything.

In fact, he often had to borrow money from the brokerage executive. By the time they tied the knot, he owed her a whopping $446,000.

“I asked her why she had no qualms lending me so much money,” says Mr. Yeo, 52. “She said she was investing in me.”

Her investment has proved to be a shrewd one.

Her husband is now founder and chief executive of JCS Group, which has six divisions specializing in fields from machinery and equipment manufacturing to renewable energy. With subsidiaries in several countries including the United States, China and Sri Lanka, the group employs more than 400 people and has an annual revenue of more than $60 million.

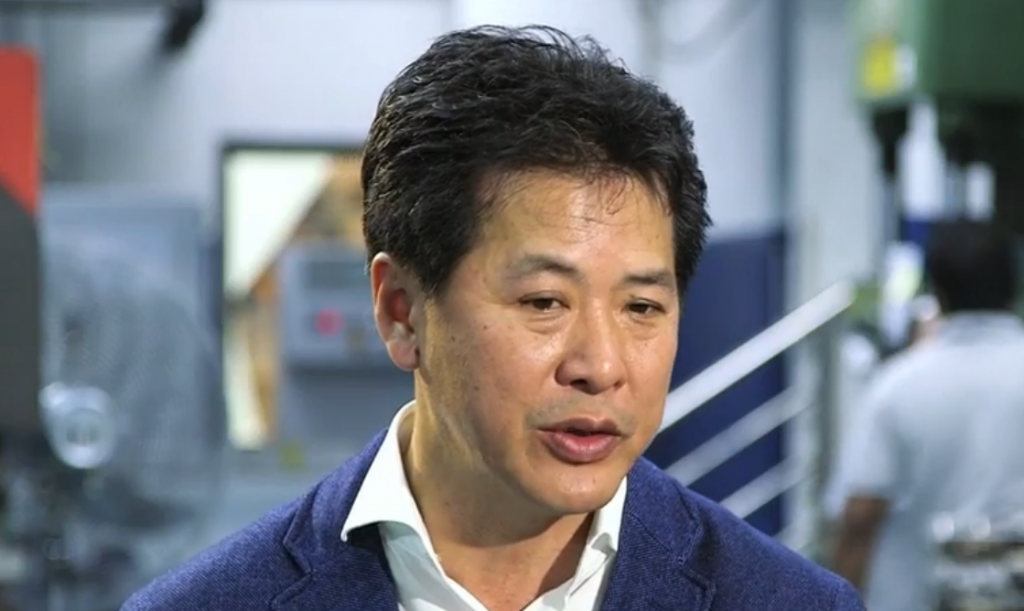

Sturdily built with a quiet dignity, Yeo is sitting in the boardroom of his JCS factory in Woodlands.

Despite his valiant attempts to stem them, tears well from the corner of his eyes as he recalls the trials and tribulations he went through before finding success.

The eighth of 10 children of vegetable and poultry farmers, he grew up in a village in Sembawang.

Life was not easy, and Yeo and all his siblings had to help out on the farm.

“I saved the five cents I was given for school every day and when Saturday came along, I would be very happy. I would spend 15 cents on a bottle of Coke, and the other 10 cents on tikam,” he says, referring to the traditional guessing game.

His interest in things mechanical surfaced at a very young age; he was always tinkering with machines and coming up with contraptions to shoot birds.

When he was 14, the former pupil of Nan Chiau Primary and later, Hwa Chong Secondary, designed a machine for one of his elder brothers who ran a small business making birdcages. The birdcage-making machine became the talk of his village in Sembawang.

“I just relied on my instincts. I visualized the machine, sketched it out and then built it by using parts bought here and from Japan,” he says.

Except for an A in Mathematics, his O-level results were mediocre. He applied to study mechanical engineering in Singapore Polytechnic, but was booted out after a few months when he failed one of his subjects.

He signed up with the Republic of Singapore Air Force, where he spent seven years as an aircraft mechanic. “I remember my first pay cheque. It was $238,” says Yeo, who was at the Air Engineering Training Institute for a two-year course in aircraft maintenance.

The air force also supported his decision to go back to school and sponsored his part-time studies for a diploma in factory automation from Singapore Polytechnic.

After seven years, he decided to strike out on his own in 1988 when he was 25.

Hoping to start an automation business, he borrowed $50,000 from a brother-in-law.

His plans, however, went awry when a close friend asked to borrow $38,000.

“He said he needed it urgently and would return it to me one or two weeks later. I’ve not seen this friend since,” he says, shaking his head.

Although he could no longer afford the machines he had hoped to invest in, Yeo went ahead with his dream and set up JCS in a makeshift workshop in a parking space outside his family home in Sembawang.

Business was hard to come by as he had no track record. To support himself, he started repairing and sprucing up old cars before reselling them.

It was not a bad living. “Sometimes I could sell five cars in a day and earn a couple of thousand dollars,” he says.

About a year later, however, he stopped the business. Speaking slowly, he says: “There was an incident. I cheated a guy.”

Instead of doing a proper welding job, he had fixed a hole in a Mazda with tin plate and touched it up.

The vehicle was sold to a handicapped buyer.

“He had only one arm. That night, I was overcome by a very strong feeling; I felt very bad,” says Yeo, brushing away a tear. “We didn’t do it properly and it was wrong. The next day, I just stopped the business.”

He poured his heart and soul into his automation business next and the next decade was bruising and punishing. Three other partners who joined him in the beginning pulled out after a few months.

“The tough times were probably retribution for what I did,” he says with a wry grimace.

He accepted all sorts of commissions, from moulds to automated pancake machines.

The business grew. Although he had to move to new premises in Marsiling and hire more people, he was not making money

“I was building machines for people, but I was losing money for every project I took on. Because I was so focused on building machines, I didn’t think about how to build the business,” recalls Yeo who built more than 80 machines in his first three years.

High production costs and tardy payments by customers drove him into debt. For nearly a year, he borrowed $50,000 monthly from an illegal moneylender.

“I got only $45,000 because $5,000 was commission. I had to pay the moneylender back on the 25th of each month, and on the 26th I would borrow again,” he says.

“One of my sisters worked for me; I owed her her monthly $800 salary for seven years. Every month, I would roll over my finances to keep the business going.”

Working 21 hours a day, he himself went without salary for nearly a decade.

Fortunately, he could count on the support of Ms. Lim, who was drawing a handsome salary working in a brokerage. They met at a gathering organized by a friend and realized that they lived in the same neighborhood.

On more than one occasion, he thought of throwing in the towel.

He remembers being stuck, literally, by a machine he was building at 3am .

“I was clamped in by two air jacks and I was in the workshop alone. I struggled and had to cut wires for nearly two hours before I could free myself. I told myself perhaps I should just give up.

“I gave myself one year to fix my problems, but one year came and went and I hadn’t fixed them, so I carried on.”

After seven years, he decided to switch tack by focusing on designing and building his own equipment.

This decision changed not only his business, but also the course of his life.

He invented a machine capable of doing precision cleaning and washing for components in high-tech industries.

JCS started making decent revenue, but a big boost came when Mr. Yeo sold a machine to a Japanese multi-national company in 2001.

Not long after, the Japanese boss came to visit JCS at their premises in Marsiling.

“He said that if he had known my factory was like a backyard, he would not have ordered his first machine,” Mr. Yeo recalls with a laugh. “But they’re still ordering from us. We have sold more than 300 machines to them; each machine cost about half a million dollars.”

The Japanese deal opened a lot of other doors for JCS. In 2001, Mr. Yeo moved out of his 3,000 sq ft factory in Marsiling to a 25,000 sq ft one in Woodlands.

He soon set up operations in other countries including China, the United States and Thailand.

“From Day One, I had wanted this company to go international,” he says.

Diversification was next on the cards. From cleaning equipment, he went on to start companies offering a multitude of other services including packing and assembly, tool and die design and manufacturing for the aviation industry and producing organic fertilizer.

Today he has six divisions, one of which is Biocair, which has come up with an alcohol-free anti-bacterial disinfectant. Tested to kill 99.99% pathogens according to the US Pharmacopoeia Standard, the spray – which is child friendly – is now sold in about 30 local stores and will soon be marketed overseas.

Mr. Yeo has visions of JCS being a master incubator, spurring innovation and nurturing new businesses from his existing ones.

In 2010, nearly two decades after starting the business, the entrepreneur decided to pursue his Executive MBA (EMBA) at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School. “I’m a good engineer, but that doesn’t mean anything. If I wanted to build a platform for technological innovation, I need to have a bit more,” he says.

Hitting the books again after such a long time was not easy.

“For nearly 20 years, I’ve never had to listen to anyone talk for a long stretch of time. Here, I was attending classes from 8am to 8pm.”

But the course, he says, did him a world of good.

“Learning to read, listen and communicate is an incredible thing. Talking to my professors and classmates made me look at my personality, re-evaluate relationships with friends and family.

“I realized that working and learning should go hand in hand,” says Mr. Yeo, who also bonded with his classmates over two grueling Gobi Desert Challenge events in 2013 and 2014.

The nearly 120km trek, which takes place over four days, is an annual NUS Business School event and tests the endurance, grit and determination of participants.

Mr. Yeo graduated with his EMBA in 2013. One of his biggest takeaways was learning “how to create space in your mind, which allows you to readjust your position”.

About five years ago, the father of two children aged 17 and 19 also started devoting time to the study of Buddhism.

He now attends at least half a dozen talks and retreats in places such as India each year.

“It’s about finding out why we are here,” he says, adding that he intends to devote more time to Buddhist studies when he turns 60.

That does not mean turning his back on JCS.

“I spent so many years accumulating wisdom and experience and learning from my mistakes. And then all of a sudden, I say bye bye? That will not be right.”

RELATED STORIES

Solid way to boost revenue by 10 times

Just 20, and his assets are worth over $100K