First in a series

Two cancer patients—one from Malaysia and the other from Myanmar—have their own story to share.

Mei (not her real name), a 32-year-old mother of three from Kuala Lumpur, first noticed a lump when she was breastfeeding her second child. Worried about the lump in her breast, she consulted her gynecologist several times and was repeatedly told not to worry since nothing was wrong.

It was only when she was pregnant with her third child that her symptoms were taken seriously and she was referred to a breast surgeon. She was shocked that the biopsy revealed she had breast cancer. Since her diagnosis was delayed, the cancer had spread to her lymph nodes. This made her angry and scared.

She had to wait until her baby was born before she could be treated. Two weeks after she was recovering from childbirth, Mei started chemotherapy to shrink the tumor. Later she underwent surgery and then radiotherapy for six weeks alongside targeted therapy.

As she was busy taking care of her three children, Mei experienced emotional stress. Thanks to the support of not only her mother and her husband but a wider network as well, she was able to survive such ordeal.

Mei’s journey continues to be a struggle, but despite this, she considers herself one of the lucky ones because her pregnancy made doctors prioritize her case and insurance covered the cost of her expensive treatment. However, she still sees the impact on her household budget of the health supplements and other out-of-pocket expenses which are burdensome, especially with three small children.

Living in Yangon, Burma (Myanmar), is 52-year-old Aung (also not her real name) who was diagnosed with stage 2 breast cancer when she was 50.

When her symptoms first arose, Aung—who has never been married—was convinced by her neighbors to see an oncologist. Her brother and cousin helped her arrange the appointment with the doctor. At first, her family was reluctant to reveal to her the result of her test, but later on, they let her know the truth.

After finding out her diagnosis, Aung received treatment at a private hospital, which was cleaner than a public one. The cost of her treatment exceeded her income so she had to raise money for the life-saving treatment, borrowing from relatives and neighbors. Aung also had to leave her job at a kitchenware stall in the local market and rent out her space to another vendor in order to pay for her treatment.

Aung’s younger brother, a key part of her support group, died of liver cancer after her diagnosis. He survived less than a year after he was diagnosed and after struggling to help pay for her sister’s cancer treatment. He didn’t let her sister know his financial struggles and tried to manage it all by himself.

Aung remarked: “Cancer has changed my life completely because in the past, I would go to work regularly and I had no worries for money. Now I can’t work and if I work hard I feel very tired.”

Her highest priority is to get well so that she can take care of her elderly mother.

Mei and Aung were among the 9,513 patients whose cost of cancer treatment were examined by a new research by The George Institute of Global Health.

Action study

The Asean Costs in Oncology (Action) study involved patients across eight countries—Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Thailand and Vietnam in the region. Aimed at assessing the impact of cancer on household economic wellbeing, patient survival and quality of life, the study provides evidence for Southeast Asian countries to put in place policies that can help improve access to cancer care. It also provides adequate financial protection from the burden of costs of the illness.

“The cost of cancer does not only affect patients, but also their families and society as a whole,” said Prof. Mark Woodward, MSc, PhD, from the George Institute for Global Health. “We hope the evidence from the Action study will help governments of countries in Southeast Asia (SEA) develop strategies and policies for combatting cancer for the long term.”

In 2012, cancer claimed the lives of 8.2 million people all over the world. There were more than 770,000 new cases of cancer and 527,000 cancer deaths in SEA. The number of new cases is expected to increase about 70 percent to reach 1.3 million by 2030.

Cancer will become an overwhelming burden on society and healthcare systems across SEA, if swift action is not taken, according to the study.

Woodward said: “When we look at the data, we can see that the costs associated with the noncommunicable diseases such as cancer are a significant driver of poverty in SEA. By creating and utilizing social safety nets, governments can prevent their citizens from poverty and economic hardship after being diagnosed with cancer.”

Key statistics

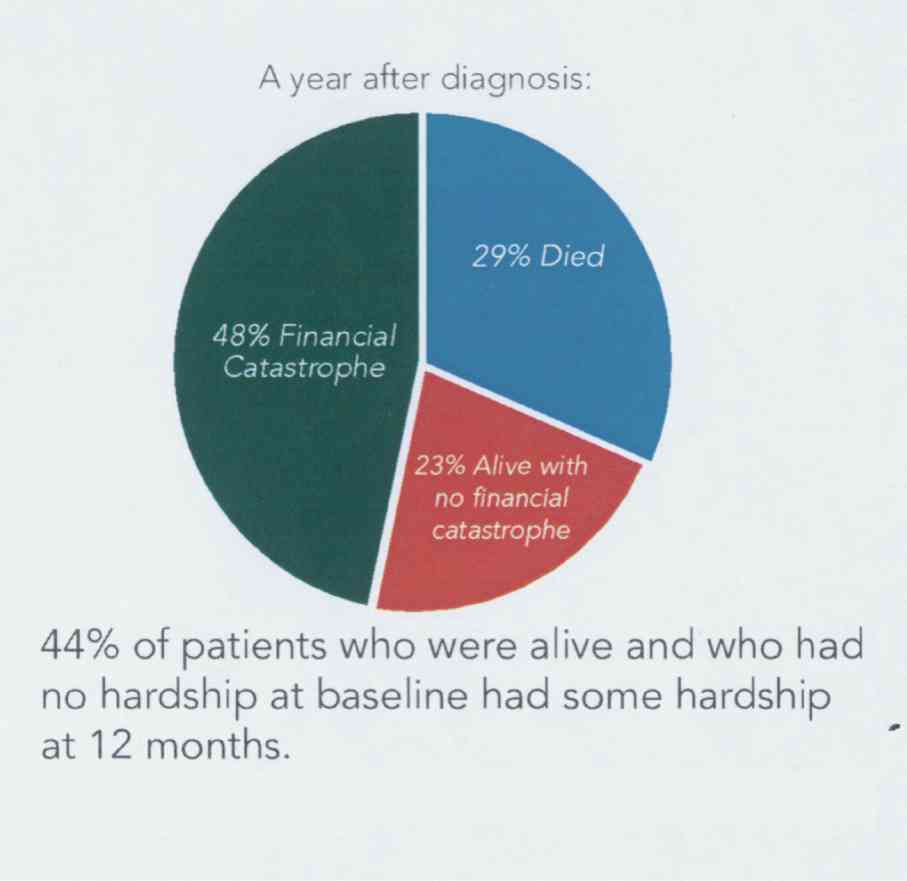

The study revealed that of the 9,513 patients followed up at 12 months after cancer diagnosis in SEA, over 75 percent of patients faced worst outcomes. Of this, 29 percent died of cancer while 48 percent experienced financial catastrophe.

Additionally, almost half or 44 percent who survived experienced economic hardship as a consequence of the cancer majority of which ended up using their life savings.

Pointed out in the study are these key points:

1. SEA risks being overwhelmed by burgeoning cancer epidemic due to aging populations and rising cancer burden.

2. Cancer diagnosis in Southeast Asia is potentially disastrous.

3. More than 75 percent of people suffering from cancer experience death or financial catastrophe within a year after diagnosis.

4. Cancer has a compounding effect on existing poverty, with low-income patients encountering the worst results.

5. Once diagnosed with cancer, Southeast Asians face devastating hurdles in getting treatment.

6. With the growing burden of all cancers in SEA, urgent action is needed to protect populations from the financial burden of disease and to reduce the impact of loss of economic productivity.

The study identified these factors associated with greater chances of financial catastrophe or death:

• Age. The older patients (over 65 years) were more likely to experience financial catastrophe or death than the younger ones (under 45 years).

• Income level. Those with lower-income were more likely to experience financial catastrophe, particularly in upper-middle-income countries.

• Education level. Lower educational levels were significantly associated with higher odds of death and financial catastrophe.

• Health insurance. Those with some form of health insurance succumbed to large debt to pay for the treatments not covered by the insurance. Patients without insurance were at higher risk of death, with regard to being alive and not experiencing financial catastrophe.

•Cancer stage. Cancer diagnosed at a more advanced stage was associated with more than five times the odds of death and 50 percent higher odds of financial catastrophe.

According to the study, the economic burden of cancer treatments to health systems, individuals and their households will grow as the availability of medical technologies and treatments expands across regions. These impacts will be felt most strongly in socioeconomically disadvantaged groups, particularly those in low- and middle-income countries where social safety nets are less likely to be present.

Cancer can therefore be a major cause of economic hardship because treatments are costly and the disease impacts people’s ability to work, the study concluded. In addition, economic hardship can have a devastating effect on cancer outcomes.