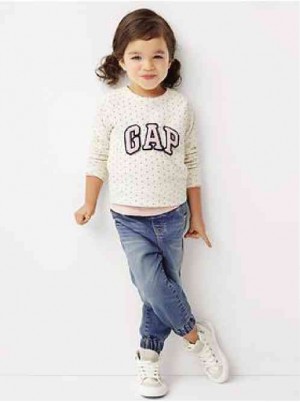

Gap scrambles to find its footing

Sharon Stone wore it to the Oscars. Madonna, Scarlett Johansson and Ashton Kutcher modelled its clothes.

Gap was the epitome of casual fashion in the 1990s.

Adored by legions of celebrities including Jessica Alba, its khaki pants and button-down shirts were quintessentially American and sought after by many outside the United States.

It has gained a following in the Philippines too, with outlets across the country.

But today, it is a different story.

Store closures

Article continues after this advertisementLast month, Gap announced that it was closing a quarter of its 675 North American stores. This came after store closures in previous years.

Article continues after this advertisementGap joins a growing list of brands such as Nokia and Kodak that have fallen from leadership positions.

Nokia, who once held as much as 50 per cent share of the mobile phone market, was slow in acknowledging and recognizing the threat that Apple’s iPhone posed with its touchscreen swipe feature in 2007. Kodak failed to see digital cameras and mobile phone cameras as serious threats.

When a company is on top, especially for a long time, it tends to be blinded by its past glory.

For Gap, it did not foresee customers wanting variety and ignored the trend toward fast-fashion retailing — the business model that H&M and Zara have thrived on at its expense.

From the moment a hot, new design is on the catwalk, vertically-integrated fast-retailers are able to have a doppelganger of that design in their stores within two weeks.

This turn-around is significantly shorter than the industry average of six to nine months.

Gap, on the other hand, does not own any factories and orders its stock some months in advance.

Like many other non-fast retailers such as Abercrombie & Fitch, Gap’s business model means it is unable to keep up with fast-changing tastes in fashion.

As a mid-priced casual wear retailer, Gap also suffers from commoditization.

Neither a luxury nor a low-end retailer, Gap does not have a meaningful proposition that sets it apart from competition. While luxury retailers have impeccable service and limited pieces as their distinctive offering, and low-end retailers offer value for money, Gap as a middle-of-the-road brand seems no different from other brands selling mass-produced clothes. Its identity is lost among the crowd of mid-priced retailers.

And when it is one among many, it ceases to be aspirational or exciting.

Companies must see beyond what customers and competitors can see.

Local companies can take a leaf from Gap’s setback as well as the success of other retailers.

Trends and interests are getting shorter as individuals have shorter attention spans. Production has to be nimble and companies have to be quick to adapt.

In Asia, where production costs are low and consumers aspire to be trendy and yet are price-sensitive, especially in less developed regions, retailers selling cheap, trendy clothes are a dime a dozen.

Uniqlo store in the Philippines’ Mall of Asia. The operator of cheap-chic clothing giant said Thursday, Jan. 10, 2013, that steady winter-clothing sales helped boost its latest quarterly net profit by 23.5 percent from a year ago. INQUIRER PHOTO

Fast turnaround

They sell clothes that are virtually brandless. How does one compete with such keen no-name competition?

Take a look at Uniqlo, which also has outlets across the Philippines.

Like competitor H&M, Uniqlo designs, manufactures, markets and sells its apparel. Hence, it has a faster turnaround than Gap, which does not control its supply chain.

However, rather than be dictated by fashion trends, Uniqlo provides customers with the basic apparel piece such as the polo shirt, in a myriad of colors that they use to create their own style.

Uniqlo has a cost advantage through bulk purchases and manufacturing and yet, offers individuality through mix-and-match pieces.

Also, its partnerships with sartorial icons such as Jil Sander and Pharrell Williams give it legitimacy.

Together, Uniqlo is able to price its apparel attractively while providing the aspirational ‘oomph’ through its design partnerships.

The combination of low price and celebrity designs, which is also the same positioning H&M uses, makes the offering a tough one to beat.

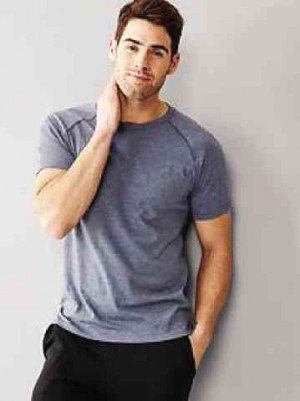

In the Philippines, Bench, too, has seen its fortunes rise. Since starting out in 1987 as a small store selling men’s t-shirts, it has grown into a leading fashion brand that prides itself in providing an array of quality products at affordable prices.

Trendy lines

It grew by expanding not just into ladies’ fashion, but also complementary lifestyle products including fragrances, houseware and even snacks.

Its trendy lines have seen Filipino film stars gracing its fashion shows.

No brand comes close as Bench meets the mark on all fronts—trendiness, quality and price.

Karimadon, on the other hand, is a brand that has grown in the depth of products offered.

Known as being the place for dresses and gowns, it recently introduced a line of ready-to-wear wedding gowns, to cater to brides who do not wish to pay an arm and leg for their big day, filling a space in a market that not many other retailers have ventured.

Elsewhere, Singapore shoe brand Charles & Keith ensures that its shoes are paired with matching accessories such as handbags and sunglasses.

This is a unique concept because few shoe brands offer such coordinated pieces. And customers want this because it makes shopping easier.

In the Middle East, Charles & Keith is in demand because the way conservative women dress means that the only visible items that women can make a fashion statement with are shoes, handbags and sunglasses.

In short, local firms must ensure they offer some value, be it low prices, value-for-money aspiration, or something distinctive.

What can Gap do to regain its footing?

It has to be market driving. It should anticipate what customers will want.

During Akio Morita’s time, Sony did just that.

Back then, people happily carried bulky and heavy boom boxes on their shoulders, blasting music throughout the neighborhood.

But Morita anticipated that a small portable device for one’s personal listening pleasure is an offering that people would want but never thought of.

This was how the Walkman was born.

Market driving requires an intimate understanding of customers that goes beyond what market research data show.

It needs management that is visionary, to see beyond what customers, and competitors, can see.

Ang Swee Hoon is associate professor of Marketing at the National University of Singapore Business School, which celebrates its 50th anniversary this year.