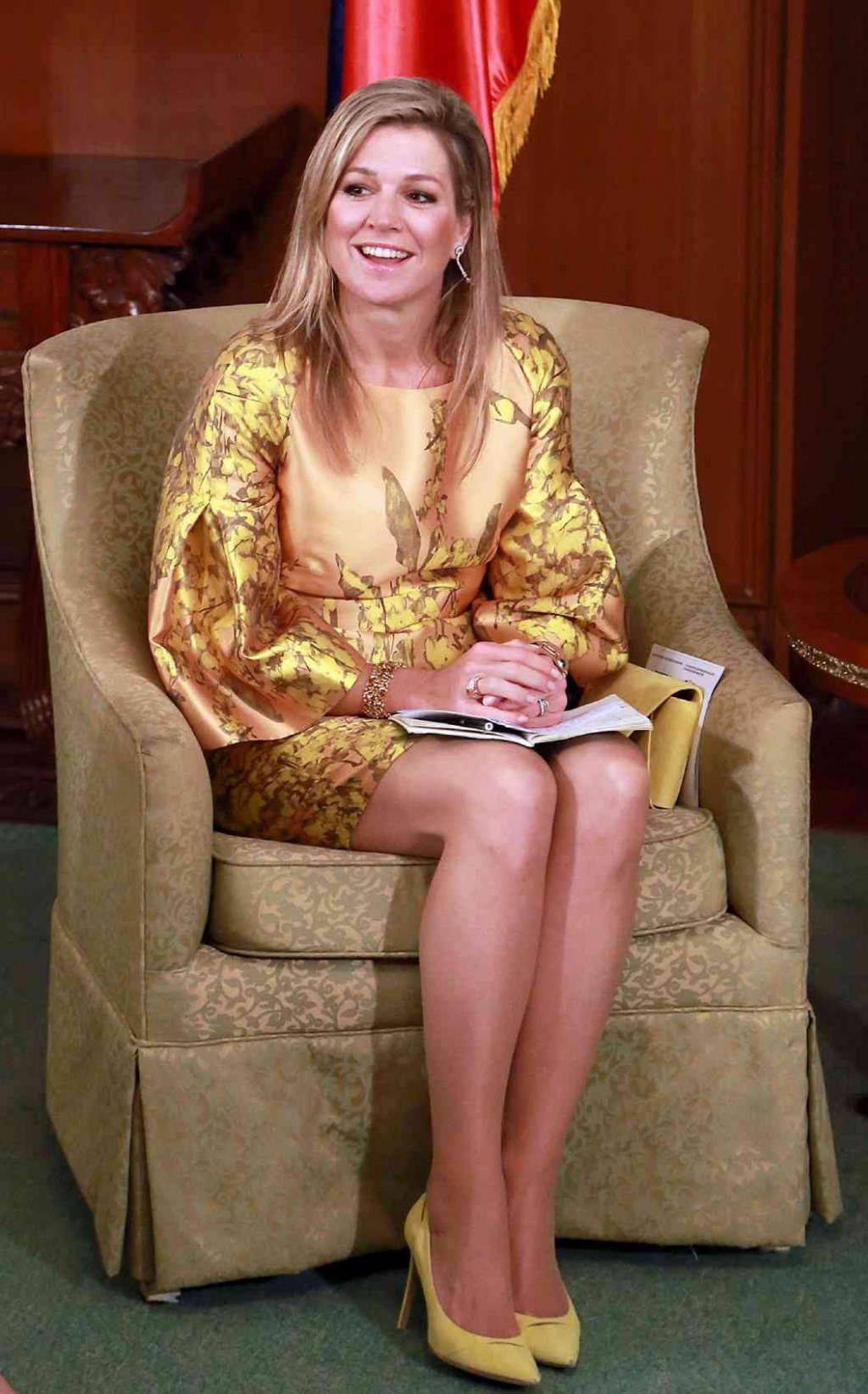

HER Majesty Queen Maxima of the Netherlands is the UN’s special advocate for financial inclusion. GRIG C. MONTEGRANDE

For the first time in history, the government has mounted a serious campaign to put loan sharks out of business, and get more Filipinos to take baby steps toward joining the formal economy.

This month, 13 government agencies, led by the Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas (BSP), launched the new National Strategy for Financial Inclusion (NSFI), an initiative that aims to empower Filipinos using financial services.

And Queen Maxima of the Netherlands—herself a native of an emerging market before marrying a European crown prince—is one of the government’s most prominent supporters in promoting financial inclusion.

“The Philippines puts a high priority on financial inclusion because it seeks to unlock economic opportunity for all, especially the poor,” said Queen Maxima in a speech in Manila earlier this month.

The Dutch monarch, who serves as the UN Secretary General’s Special Advocate for Financial Inclusion, was in the country at the start of July to lend her support to the state’s efforts to get more people to open new bank accounts.

During her three-day stay, she visited several small businesses in Tagaytay City, meeting with the “small folk.”

She also called on President Benigno Aquino III in Malacañang, before delivering a speech at the Philippine International Convention Center on financial inclusion.

The failure of the formal financial sector, mainly banks, to reach larger portions of the population is a result both of economic stability in the past, and the country’s own geography. Banks’ ability to reach out to smaller borrowers, who are often more risky, was hampered by past financial crises.

Putting up branches in far-flung areas, where communities are poor and clients are few, has also proven difficult. As a result, the habit of keeping savings at home has taken root, the central bank said.

Filipinos who need quick financing also often fall prey to so-called “five-six” loan sharks, known for charging interest rates upward of 20 percent.

Solving this financial gap in the population is vital in reducing poverty and unlocking the economic potential of those in informal sectors, officials said.

“Insurance protects farmers against flood, credit enables small businesses to grow to larger ones, families can save for tuition, and payments channels that are cheap allow families to send and receive money more affordably,” Maxima said.

Globally, Maxima said “millions” of people fall back into poverty every year due to sudden medical expenses alone. Most cases can be avoided with proper insurance coverage.

The Philippine government’s response to the financial inclusion challenge, as outlined in the draft NSFI, will focus on three areas: Policy regulation, financial education and consumer protection and advocacy programs.

In its first national baseline survey for financial services, the BSP found some alarming statistics.

Many Filipinos don’t save money at all, BSP Governor Amando M. Tetangco Jr. said. “[About] 65 percent of unbanked adults cited lack of money as the main reason for not having a bank account,” he said. And among those who save, seven in 10 keep their cash at home.

When borrowing money, the survey showed a similar trend of preference for informal institutions and mistrust of formal channels.

About half of adult Filipinos borrow money on a regular basis. The main sources of financing were informal lenders, namely family, relatives and friends.

About 62 percent of all loans came from these sources, while 10 percent came from other informal lenders such as pawnshops or neighborhood loan sharks.

Banks as source of borrowing stood at 4.4 percent, lower than the percentage of adults who borrow from loosely regulated lending and financing companies (12 percent) and cooperatives (10.5 percent).

Officials said some problems were more complex and may be difficult to solve. The BSP in the past has said many Filipino still feel intimidated by bank branches, so they prefer to hold on to their money rather than handing it over to strangers.

Other problems, however, are simpler: Most financial institutions are simply too hard to get to for many Filipinos.

The average length of time to reach the nearest bank and ATM is 26 minutes and 22 minutes, respectively. A two-way trip to the nearest bank and ATM costs P52 and P47, respectively. Length of travel time and cost of travel are lower for other access points such as remittance agents and payments centers.

Some access points such as cooperatives and e-money agents are most commonly reached by walking.

On the average, it takes 21 minutes to go to the nearest access point. In terms of cost, the average roundtrip fare to reach an access point is P43, the survey showed.

These were some of the data that guided the drafting of the NSFI.

Spearheaded by the BSP, the NSFI was put together by an interagency committee of 13 agencies, including the Departments of Budget and Management, Education, Finance, Social Welfare and Development and Trade and Industry.

Also involved were the Insurance Commission, National Economic and Development Authority, Philippine Deposit Insurance Corp., Philippine Statistics Authority, Securities and Exchange Commission, Commission on Filipinos Overseas and Cooperative Development Authority.

Tetangco said while the government would do its best to create a regulatory environment that promotes the expansion of banks into the countryside, much of the work would still have to come from the private sector.

Among the innovations that the BSP is banking on is the rise of electronic payments channels. Tetangco wants interoperability of financial services that will allow, for instance, users of Globe Telecom’s G-Cash and Smart Communications’ Smart Money mobile wallets to send money to each other.

Progress, he said, would be monitored using nationwide surveys on financial access to be done every two years.

“This will help us make an honest assessment if we are indeed making a difference in the lives of Filipinos,” Tetangco said.