The business community had high hopes that the Aquino administration would usher in a new age of economic renaissance for the Philippines when it took the helm of government in 2010.

This sense of anticipation was heightened further when the President unveiled the cornerstone of his plan to boost the economy and bring the country on par with its rapidly developing neighbors—an innovative scheme called the Public-Private Partnership (PPP) program that would harness the resources of the private sector toward state-directed spending priorities, especially in the infrastructure sector where the Philippines lags far behind its regional neighbors.

Five years later, however, the promise of PPP remains largely a potential except for a smattering of relatively small deals that are now underway but will, in all likelihood, not be completed by the time the administration leaves office in mid-2016.

For the most part, the businessmen who were counting on these projects to move the country higher up the competitiveness chain have resigned themselves to the reality that the burden of closing the economic gap between the Philippines and the other members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (Asean), for example, will fall on the shoulders of the next administration.

Employers’ Confederation of the Philippines (ECOP) president Edgardo Lacson said his to-do list for the next administration was a long one. But the top item was creating job-generating opportunities.

He also stressed the importance of ensuring easy access to affordable education; developing and strengthening the agricultural sector, and providing the public with easy access to shelter.”

Lacson, who also sits on the board of the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE), said that the next administration should also “develop and upgrade the country’s infrastructure” along with a parallel thrust of “lowering the cost of power and ensuring stable power supply.”

He said the next President should make it his mission to give the country a more competitive tax regime, while helping put in place less restrictive economic provisions in the Constitution.

“Finally, we should have good governance and transparent government records,” the Ecop chief said.

Meanwhile, the research head of stockbrokerage Campos Lanuza and Co., Jose Mari Lacson, pointed out that developing the country’s infrastructure was item “number one” on his list.

More importantly, he said that future infrastructure deals under the next administration should have strong provisions that would insulate project proponents from the widely expected rise in interest rates that, in turn, would make the cost of capital more expensive in the coming years.

Lacson also said the next President should prioritize changes to the 1987 Constitution to encourage greater competition within the Philippine economy. “At this point, our local conglomerates are already big enough to take care of themselves,” he said. “Companies like PLDT and others should get more competition from abroad to encourage innovation.”

For former budget secretary Benjamin Diokno, the focus for the next presidential administration should be virtually the same as what the current administration should have focused on five years ago.

“The next administration should address the current constraints on the country’s growth,” said Diokno, who is also a professor at the University of the Philippines’ School of Economics and a known critic of the administration’s economic policies.

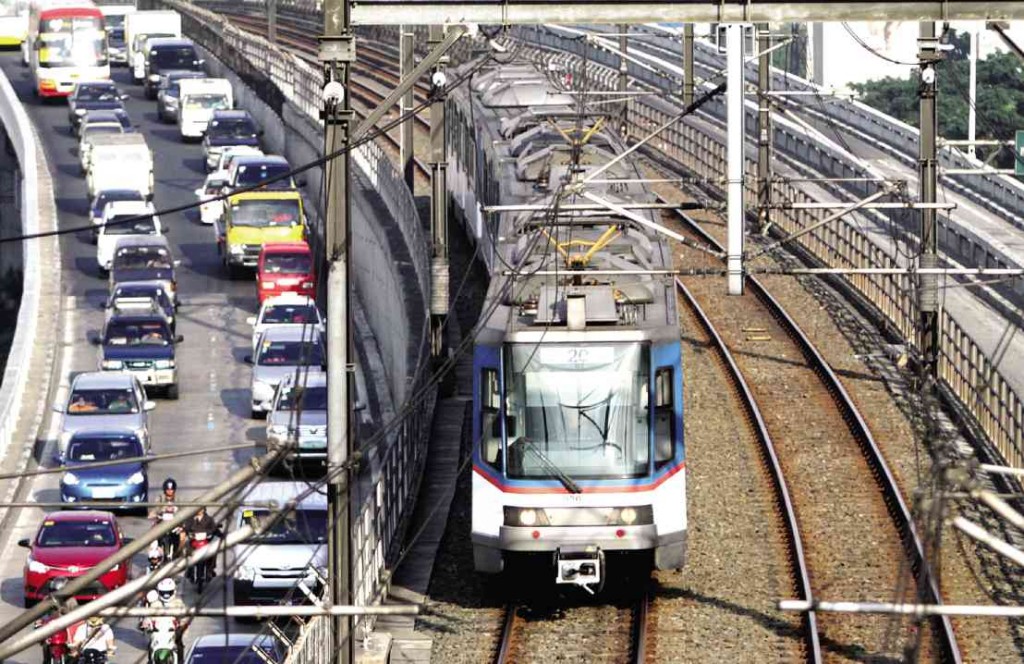

“We need infrastructure. We need cheaper electricity. We need more roads, modern airports and seaports,” he said. “The backlog on these projects is just too big.”

Diokno said that, at present, the Philippines stands anywhere between 10 and 20 years behind the most advanced Asean economies—which are its very same competitors in the global marketplace—in terms of infrastructure.

Diokno, who served as budget secretary in the Estrada Cabinet, also pointed out that longstanding issues that deter more foreign investors from setting up shop in the Philippines remained. “The next administration should have a strong focus on attracting more foreign direct investments,” he said, explaining that many legal restrictions, including those found in the 1987 Constitution, hobble the Philippines’ economic progress. “Thus, opening up the economy [to foreign businesses] is very important.”

Also, persistent complaints by both local and foreign businessmen about the relatively high cost of doing business in the Philippines—from lengthy delays encountered when securing business permits to the costs associated with sudden changes in government policies —have to be addressed.

“The cost of doing business has to be brought down,” Diokno said. “Consistency is important, so there should be no flip-flopping in government policies.”

Finally, the economics professor said that greater effort must be put into making the country’s growth more inclusive to benefit not only those at the top of the economic pyramid but also those at the bottom.

“The next administration should focus on agriculture,” he said. “There are a lot of small- and medium-sized projects that the government can implement to increase agricultural yield because, remember, this sector employs one-third of the country’s workforce.”

Diokno welcomed the expiration of the law governing the land reform program, which, he said, has yielded a mixed bag of results.

“There should be no more extension of agrarian reform,” he said. “With the land reform program ended, there will be no more uncertainty. With the land reform program, landowners didn’t want to invest in agriculture because they weren’t sure if their land would suddenly be taken over by government.”

Amid all these items on its to-do list, the next administration will have to work toward checking all the boxes in a global and local economic environment that will be—by most accounts —less friendly than the one the Aquino administration found itself in.

One such headwind that the Philippines would likely encounter is rising interest rates around the world, which will make the cost of capital rise for everyone in the market.

This means that funds needed to built critically needed roads, airports and seaports, among others, will be more expensive whether the party that will be doing the spending is the government or a private corporation.

Indeed, what is clear is that whoever becomes President in 2016 will have his or her hands full on the economic front —and a long to-do list to grapple with.