When the real estate boom in the Philippines shifted to the suburbs in early 2000s, the government and private developers invested in housing and corporate projects outside Metro Manila. Collectively called the “peri-urban jungle,” this conceptual region includes municipalities in Rizal, Laguna and Cavite.

Consequently, the region has attracted throngs of migrants, not just from Metro Manila or other parts of the country but also returning overseas Filipino workers who invest and purchase housing units.

Dr. Andre Ortega of the University of the Philippines Population Institute believes this phenomenon results in different forms of spatial mismatch.

Ortega said: “Peri-urban is not a formal space delineated by the state. The state demarcates political and theoretical space but on the ground, space is relational… Peri-urban is a conceptualized region enabling us to think of the kind of expansion going on beyond Metro Manila.”

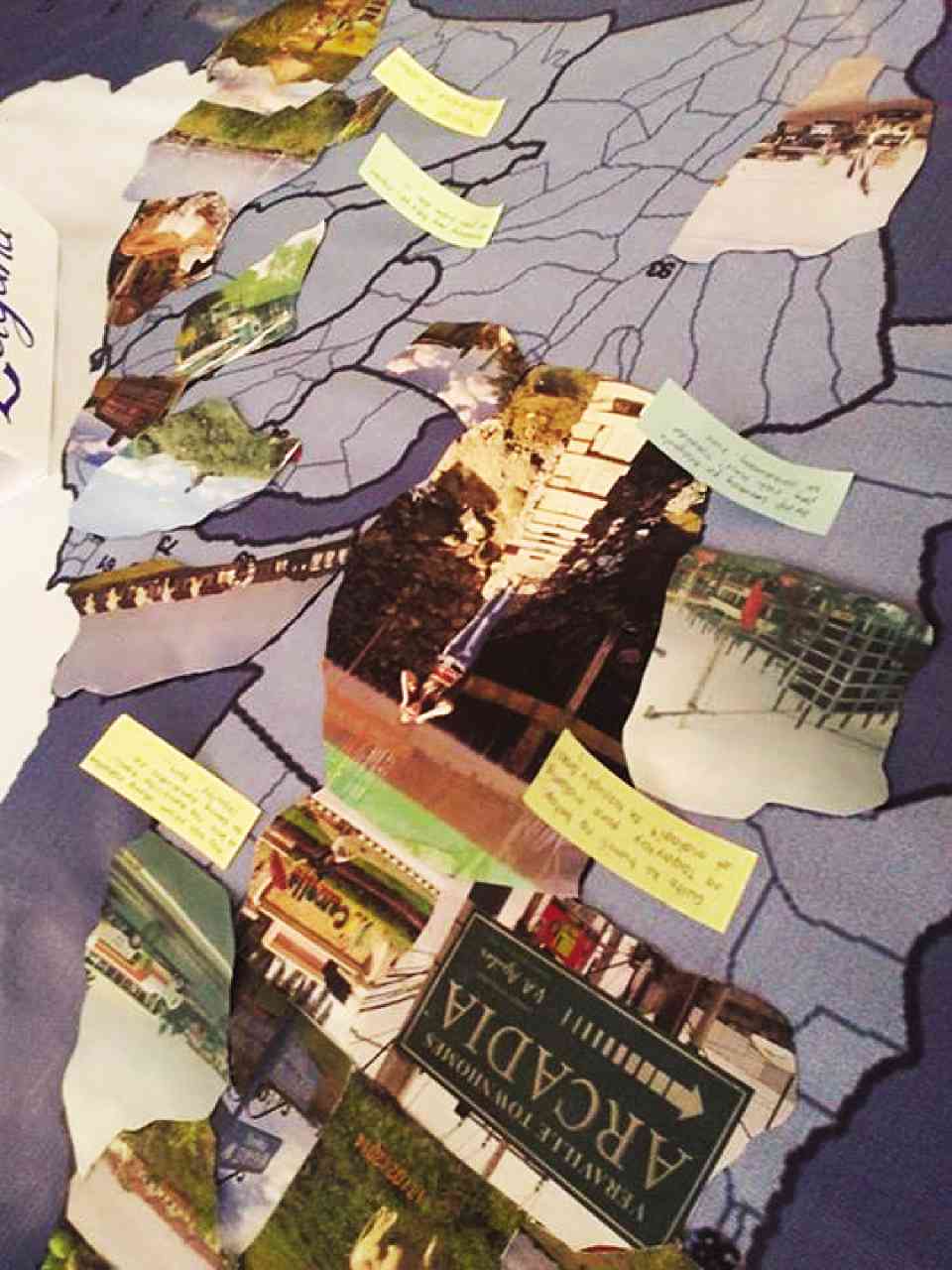

Ortega’s ongoing project “Spaces in transition: Mapping Manila’s Peri-urban Fringe” aims to map rapid spatial transformations that have been taking place outside Metro Manila. The study aims to explore how the political, economic, demographic and cultural processes of this functional region have been affected by dramatic urban-rural changes.

The two-year project started in 2013 and employed a mixed-methods approach. The quantitative part involved a survey of 2,080 respondents with a sample of barangays representative of 16 municipalities around Metro Manila. The qualitative part of the research, meanwhile, used both ethnography and archival work through interviews, site visits and field work.

At the heart of the methodology, according to Ortega, is to uncover the histories of the areas involved, to discover what’s going on underneath the veneer of new urban developments.

AN ETHNOGRAPHIC map of Laguna from the project’s interactive exhibit at UP Vargas Museum. ASTRID ACIELO

Memory of space

He said: “We need to uncover all these histories so when people drive along [these areas] they’ll recognize the history, the memory of space. Memory is very powerful and political. The spirit of the project is to ask mobility patterns of residences in gated communities, slums and other built environments in the peri-urban area… to explore their origins and sense of belongingness.”

An example of a place with a rich history but has now succumbed to urban transformations is the Canlubang Sugar Estate. Bought by Jose Yulo from Vicente Madrigal in the 1940s, the sugar estate, according to Ortega, is tied to stories of the landed elite, circumventing land reform and the privatization of space. When sugar prices fell in the ’70s, the estate was divided among the Yulo children, and the land was developed by parcels.

Significant changes in the peri-urban fringe started during the Marcos administration. Dasmariñas, Cavite, was a resettlement project of Imelda Marcos before it became a city in 2009. Antipolo, meanwhile, was seen as an alternative dwelling place as early as 1981. Marcos wanted to make Antipolo a first-class tourist attraction through four programs: 1) completion of the Sumulong Highway, 2) redevelopment of Hinulugang Taktak, 3) construction of BLISS housing units to accommodate growing household population and 4) beautification and reforestation of Antipolo’s roadside. Both projects are part of the government effort to decongest Manila in the 1980s.

Ortega said: “Oftentimes you can’t find narratives of these in documents; you need to go out there, which is very different from urban planners or people who do spatial analysis. You have to be there to actually see how space is being transformed… to see lands, communities and their experiences.”

A WHITE cow grazes on an open field, with a row of houses in a real estate development site in General Trias, Cavite, as the background. ERIC SISTER

Key impacts

He also enumerated three key impacts of the rapid transformation to local communities. First is sense of alienation to space. An example, he said, would be the people living in Antipolo and other towns of Rizal who had to travel several hours a day to reach their workplaces or schools based in Metro Manila. There is a sense of detachment to their homes, schools or workplaces.

“Alienation… is very alarming, because how can you think of a sustainable environment when you’re disconnected from your place of work or residence?” said Ortega.

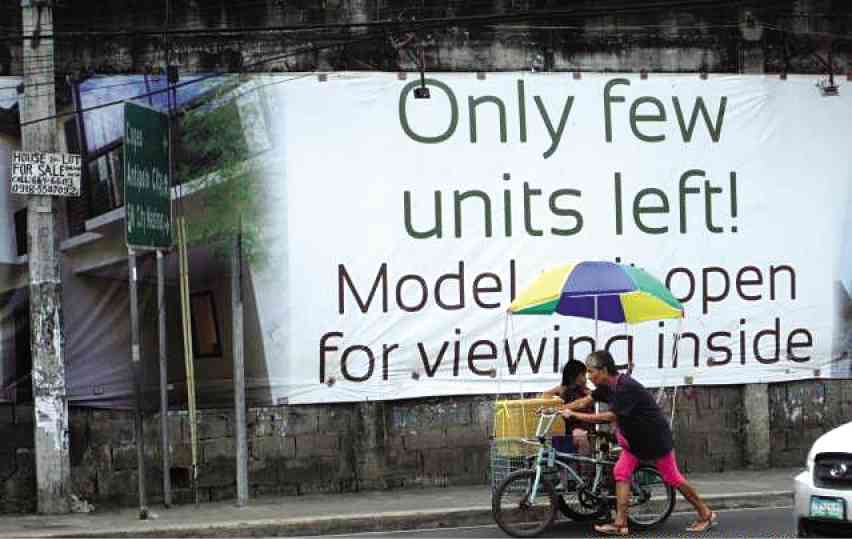

Another, he said, is class relations. For developers, the rational use of space is to develop condominiums and other high-rise establishments. These are often seen as signs of progress and development amid the rural backdrop of the communities. Ortega sees this as a landscape of content.

“You can only experience these new urban developments and green sustainable environments inside this privatized space, if you own a unit,” he said.

Sense of belongingness to these communities also changed its meaning. Since most of the residents inside the gated subdivisions are owned by OFW parents with the elderly left to take care of the home and children, a transnational suburbia is being created.

Ortega said: “Practice of suburban life is tied with transnational movement; [the family] is never complete. When you think of suburbia, you think of the rural concept in the US family, but we can never reach that sense of community because of OFWs. Some, meanwhile, long for their life in the province.”

Spaces in Transition is currently in its data processing stage. Series of monographs and a website that will contain results of the project will be released by yearend. As the project draws to a close, Ortega urges the public to look at multiple forms of dispossession, cultural changes and impacts of developments, especially in agricultural communities.

“The project wants to not just deconstruct space but to argue that space is constructed through social relations not space drawn on paper, but space tied to everyday life. That’s a major aspect of the project, that we’re not dealing with abstract space designed by planners. We want to critique these designs,” he said.