Egg shortage cutting into restaurant profits, menu items

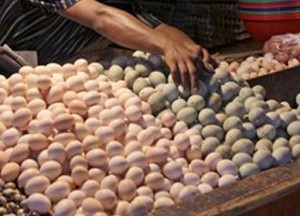

A shortage of eggs in the US due to bird flu is threatening supplies and profits of restaurants in certain states. AP FILE

OMAHA, Nebraska, United States — Those who like to indulge in a good omelet or quiche at the local cafe should prepare to pay a little more — if it’s even on the menu.

Restaurants are struggling to deal with higher egg prices and an inability to get enough eggs and egg products in the midst of a shortage brought about by a bird flu virus that wiped out millions of chickens on commercial farms this spring. Some restaurants are pulling especially eggy dishes off menus while others are contemplating raising prices until the supply returns to normal.

Getting eggs from a smaller, local producer — which have largely been spared from the outbreak — has not protected Omaha restaurant owner Nick Bartholomew and other independently-owned eateries. His supplier’s inventory has dwindled to meet demand and production is down because of testing by federal safety officials. And the restaurant’s overall production costs have gone up by 15 percent in recent weeks, so he says he’ll have to raise prices soon.

“We’re now having to use three or four different producers and call around to different chicken farms to see what is available and when it will be available,” said Bartholomew, whose restaurant, Over Easy, serves breakfast and lunch with a focus on local ingredients. The restaurant has already taken strata — an egg casserole similar to quiche — off the menu.

The H5N2 avian flu virus began showing up in Midwest commercial turkey and chicken farms this spring. To date, 48 million turkeys and chickens have died or were euthanized to prevent the virus from spreading further. The frequency of new cases has slowed dramatically in most states, though agriculture officials said last week that an Iowa chicken farm with 1 million egg-layers tested positive for the virus.

Article continues after this advertisementBecause of the egg crisis, the U.S. Department of Agriculture lowered its forecast for table egg production this year to 6.9 billion dozen, a 5.3 percent drop from 2014. By late May, the price for a dozen Midwest large eggs had soared 120 percent from their mid-April, pre-bird flu prices to $2.62, industry analyst group Urner Barry said.

Article continues after this advertisementPrices began falling last week, but officials say it could take up to two years to return to normal production.

“The best-case scenario, we’re talking about a year before the availability is more robust,” said John Howeth, the American Egg Board’s senior vice president in charge of food service and egg product marketing.

At Hi-Way Diner in Lincoln, Nebraska, owner Scott Walker said the surge in costs may force him to pass it along to his customers. The restaurant includes two eggs with every breakfast order, and offers an optional third egg for free. That comes out to more than 5,000 eggs a week, and the price per case has more than doubled to $37 since mid-April.

“I’m absorbing it right now, but I am due for a price increase,” Walker said.

A popular breakfast spot for more than 20 years in Des Moines, Iowa, is contemplating a surcharge of 50 cents to $1 to each of their egg-heavy dishes because cases have rocketed from $18 to $40 in just a few weeks.

“It’s costing us between $400 and $500 a week,” Waveland Cafe owner David “Stoney” Stone said.

It’s not just independent restaurants being affected, either. Restaurant chains, which typically have set-price contracts for food supplies, have seen those deals rescinded.

“Our contracts have been nullified until this is cleared up and the supply gets back on track,” said Amy Rhoads, vice president of licensing and human relations for the parent company of Littleton, Colorado-based Le Peep restaurants, which has 54 restaurants in 12 states.

Nearly every Le Peep menu item includes eggs. There are no plans to change that, Rhoads said, because eggs are “so much a part of who and what we are.” But the shortage is raising the chain’s costs significantly, and as a result, their prices are going up.

The uncertainty of how long the shortage will last is what’s most disconcerting for restaurant owners, Rhoads said: “It’s one of those things that, when you don’t know how bad it’s going to get or when the end is in sight.