Working to sustain high level growth, the Philippines cannot afford power outages in the same way that a runner would not want to suffer muscle cramps while in a race.

Business leaders are worried—some may be worrying too much—that Luzon, the center of domestic production, could relive the 1990s. Back then, daily outages or “brownouts” lasted three to 10 hours, with varying degrees of predictability.

Dim summer

The Department of Energy (DOE) and the National Economic and Development Authority (Neda) have yet to come up with rules of thumb for estimating how much potential GDP growth is lost per megawatt (MW) of unserved power demand.

There are, however, clues on the close relationship between power and productivity.

Adopting methodologies from Japanese researchers (Mizobata, Kanda, Suzuki, 2011), Valenzuela City Representative Sherwin Gatchalian said in a study that the Philippines could lose P81.63 billion in real gross domestic product (GDP) from a power crunch from March to May.

Besides foregone income on lower productivity, power disruptions could increase workers’ health risks amid the summer heat, turn off investors, and drive up the prices of goods and services, according to leaders of various chambers of commerce.

Another perspective: based on its average power rates and hourly sales in 2014, Manila Electric Co. sold about P27 million to P30 million worth of electricity in its franchise areas, such as Metro Manila and nearby provinces.

Imagine the lost sales, just for Meralco, if power interruptions occur one to two hours for at least two weeks this summer, say, from March to May. Then imagine the sales that unlit stores, aircon-less restaurants, computer-dependent offices, equipment-makers and other establishments all over Luzon could miss at the same time.

How short on power are we? During the Congressional hearings on the proposed special powers for President Aquino to deal with the power crisis, DOE assistant director Irma Exconde said the problem had to do more with “reserves” than “deficit.”

She said having the exact amount of supply and demand was a recipe for outages, so Luzon needed extra power capacity of about 678 megawatts (MW). Included in the 678 MW is a buffer of 647 MW—the capacity of one unit of the country’s largest power station (Sual coal-fired power plant).

Having less power than the required buffer makes Luzon vulnerable to one-hour rotating brownout per day for two weeks or even worse, said National Grid Corp. of the Philippines (NGCP).

Without additional power plants, DOE estimates that reserves may be thinnest from May 14 to 22 (122MW) and from May 21 to 27 (82MW).

Worse, there may be outright power shortage from April 4 to 10 (40 MW) and from April 11 to 17 (135 MW).

Tangled lines

How did Luzon find itself at the precipice of another power crisis?

There is the temporary shutdown of the Malampaya gas platform from March 15 to April 14 so a new platform that would keep future production stable can be installed.

While this happens, the power output of gas-fired power plants supplying about 40 percent of Luzon’s electricity will likely lessen as plants shift to other fuels.

Without the additional capacity on the supply side or a reduction in the “demand” side of the power equation, Luzon will be in a “tight” power situation.

The current power issues stemmed from government mismanagement of the power industry in the 1970s and 1980s, and later, from under-investment in the power sector as it went into transition with the Electric Power Industry Reform Act’s (Epira) passage in 2001.

Epira is perhaps most remembered for the privatization of cash-strapped National Power Corp.’s generation assets.

While Epira untangled the power market enough to get power plants running, consumers have yet to fully enjoy its rewards, said former Energy Secretary Francisco Viray, now president of Trans-Asia Oil and Energy Development Corp.

First, Epira’s implementation was delayed, industry experts said, due to the slow regulation-setting process in the Energy Regulatory Commission and the process of establishing the Wholesale Electricity Spot Market.

The Open Access program, which allows big customers (those using 1MW and up of electricity monthly) to choose their own suppliers, is not yet mandatory.

Many electricity cooperatives under the National Electrification Administration’s purview are still inefficient and tied down by provincial politics.

Investors in power generation have noted challenges in obtaining permits and the need to upgrade electricity transmission facilities to handle new projects.

Notes:

Green bars indicate current gross reserves: energy capacity that remains when peak demand and projected forced outage from existing capacity are subtracted from total capacity.

Regulating Reserve: required energy capacity to stabilize energy frequency, or the flow of electric charge, transmitted to power users; equivalent to 4 percent of peak demand for Luzon

Contingency Reserve: required capacity to make up for the loss of the largest generating unit in the grid, equivalent to 647MW for Luzon

Dispatchable Reserve: energy or de-loading capacity from power stations not connected to the grid but can quickly replenish the contingency reserve whenever a generating unit trips or a loss of a single transmission interconnection occurs; current reserves are far from meeting dispatchable reserve requirements

The 1997 Asian financial crisis and other global events have overtaken the Epira, Viray said. There was the commodities boom that peaked in 2011, when benchmark Brent crude peaked at $116 per barrel over Mideast and African unrest.

Then, there was the issue of environmental concerns versus development, which recently gained prominence, other experts said.

Remember the 600-megawatt (MW) coal power plant in Subic by the consortium Redondo Peninsula Energy Inc. (RP Energy)?

That plant could have been finished by this summer, supplying most of Luzon’s needed power reserves, but was stuck in legal battles since 2012.

The project was finally approved last month as the Supreme Court dismissed the Writ of Kalikasan case against it. But don’t expect an instant helping of 600MW of electricity. Power projects of this size take three years or more to complete.

Calls for amending Epira surfaced recently as the Luzon power crisis loomed. To that, Viray said, “Amendments may come someday and fix the deficiencies of the law, but they will not address the current situation, and certainly not overnight.”

Business groups said amendments would only create uncertainty among investors, who were looking for consistency in regulations and laws.

Amid the cacophony of voices alarmed by the specter of power outages, what must an economy racing for growth do?

For economist and former Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno, “this is too much ado about nothing,” apparently referring to all the concerns over the possible power crisis.

Diokno said the El Nino phenomenon would be mild and there should be little impact on hydropower plants.

If anticipated, one to two hours of outages in the short term could be addressed by “aggressive measures” by government and private firms, he said. Measures such as adjustment in working and mall hours will help minimize lost productivity.

The key words are, of course, “anticipated” (or scheduled, in the case of outages) and “short term.”

Former Energy Undersecretary Jose Layug Jr. said that since it would take a long time to build large plants or enough medium-sized ones for the same power boost, the short-term cure was to curb electricity demand and ease the strain on the supply.

ILP: plugging the potholes

At 9 a.m. on March 6, 2015, an engineer at SM City Baliwag switched on the mall’s generator set as part of the dry run for the Interruptible Load Program (ILP).

The morning shift for the ILP is set from 10 a.m. to 1 p.m. but the 16 SM facilities on morning shift for the dry run started early.

The rest of the 40 participating SM malls, buildings (Savemore, Hypermarket, By the Bay, SMDC Jazz, SMDC Mezza, SMDC Sun) and corporate offices went on the afternoon shift from 1 p.m. to 3 p.m.

SM Supermalls president Annie S. Garcia said via e-mail that “total actual deloaded capacity from SM (group) was 95 MW, even higher than SM’s commitment of 80 MW.”

Citing Meralco, which is leading the ILP implementation in Luzon, Garcia said the total commitment from all “contestable customers” (those with 1 MW or more of consumption), where SM belongs, was at 176.9MW.

Meralco’s head for utility economics Lawrence Fernandez said the ILP dry run on March 6 and Feb. 18 were meant to check if procedures were laid out well and to get participants used to the process.

Under the ILP, businesses with generator sets use their own electricity and refrain from getting power from the grid during peak hours.

For doing so, they will be able to reimburse their fuel cost and get a “reasonable” fee for the use of their gensets as set by the Energy Regulatory Commission or ERC.

The DOE had worked on various options such as renting diesel gensets and rescheduling power plant maintenance. But lawmakers have ruled out genset rentals. There are limits to moving scheduled maintenance at the risk of power stations “tripping,” which will prolong outages.

The main stopgap measure turned out to be the ILP. How much can it help?

Stopgap measure

Remember that Luzon must always have 647 MW of “reserve” power. Remember, too, that the dependable capacity of 11,389 MW was a nominal figure as there are underperforming plants and plant outages, whether scheduled or unexpected.

Using historical trends, the DOE calculated the likelihood of forced plant outages that could crimp Luzon’s electricity supply. The agency projected 631 MW of forced power plant outages for March, 712 MW for April, and 642 MW for May.

As of March 9, 2015, a total of 914.93 MW deloading capacity, with 667.29 signed up and a potential for 247.64MW, Meralco SVP Al Panlilio said.

The ILP is only 40 to 70 percent efficient, however, so consumers must still save energy to help prevent outages, Energy Secretary Carlos Jericho Petilla said.

And there’s no such thing as free power.

There is a cost for fuel and the use of gensets for ILP participants. Whether the consumer or the government pays for the cost recovery is a matter that lawmakers have yet to resolve through their bicameral meetings.

Congressmen want the government to pay for the ILP cost using the Malampaya fund. The House Committee on Energy chairp, Oriental Mindoro Representative Reynaldo Umali, said every centavo increase in power rates due to the ILP or otherwise would cost the country and its consumers about P700 million.

Senator Sergio Osmena III said passing on the cost to consumers would make the cost transparent as a line item in monthly bills and make people save power.

While some would rather have outages, others would rather pay if it means they can keep working, running their business, or just to avoid having to sweat buckets.

Looking ahead

Economic activity tends to spur electricity demand, the DOE said. In its estimate for the Luzon grid, for every 1-percent growth in gross domestic product, electricity consumption rises by 0.6 percent.

But the reverse could be true as well, although experts have yet to establish a way of measuring this.

What is certain is that the power issue has become a source of concern even for economic managers. The “thin power reserves in the second quarter of 2015” are among the economic risks monitored by Neda.

Economic Secretary Arsenio Balisacan said that to stay on a fast-paced growth path, the Philippines has to rebalance its economy from one driven by consumption toward one that depends more on investments and net exports.

How? Through revived manufacturing and agribusiness, which need power.

As things stand, the power issue is distracting.

Commenting on the hype over Luzon’s power situation, Diokno said, “I think it is more to cover up for the administration’s lack of foresight. There would have been no need for emergency powers if the administration had paid attention to the power requirements of a growing economy.”

A growing economy needs about 600 MW of new capacity every year.

Business leaders from the Philippine Chamber of Commerce and Industries, Management Association of the Philippines, the Philippine Independent Power Producers Association Inc, and even power companies are pushing for new plants.

“Power competition will only be successful if there is ample supply,” Viray said.

As Luzon saw in 2013, power rate hikes could sneak in amid tight supply situations.

Yet true competition seems far off at this point.

Consumer group CitizenWatch expressed concern that the ILP cost recovery had not even been resolved, and lawmakers are scheduled to go on recess by March 20.

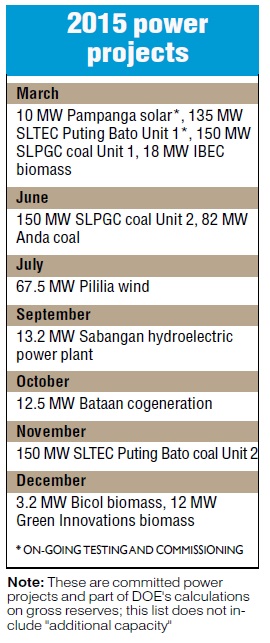

Beyond summer, the DOE expects additional capacity (those not yet included in current calculations as “committed projects”) to boost power supply for the rest of 2015. The 100-MW Avion and 40-MW Majestics projects are among those, the DOE said.

“I think things will be better in 2016 and beyond. Supply will be better. But not necessarily prices,” Diokno said.

While Philippine power sector trudges toward supply stability, will outages matter as much as price?

For Petilla, what is certain is, “The most expensive power is to not have power.”