By Dante M. Velasco

Contributor

BISHOP Jorge Mario Bergoglio, now Pope Francis, has been in the world’s headlines since he was chosen Bishop of Rome and leader of Catholicism around the world.

Last Friday, the Pontiff made a state visit to the President of the Philippines, and we saw first hand that it was no ordinary visit.

The “radical Pope,” according to an article in the latest issue of the Reader’s Digest, was in Tacloban, Leyte, to be with the survivors of Supertyphoon “Yolanda.” It is very much in character that this Pope would be with suffering people, people who have admirably shown the “triumph of the human spirit.”

He was also set to meet leaders of diverse faiths in the Philippines—Protestants, Evangelicals, Muslims, Jews, et al.—and deliver a clear message that interfaith dialogue leading to unity is a possibility devoutly to be wished.

Pope Francis has captured the imagination of the world and has opened possibilities of dialogue due to his openness with various faiths and religions.

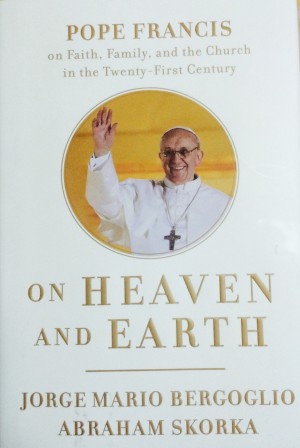

The English language translation of the book “On Heaven and Earth” is recently off the press, and has thus made available an interesting dialogue—or “encounter”—between the then Archbishop of Buenos Aires Bergoglio and Argentine rabbi Abraham Skorka. The first edition was published in Spanish in 2010.

The conversation between the two religious leaders in Argentina in this book may be dated. And yet the more recent pronouncements of now Pope Francis have been consistent with doctrines, beliefs and principles enunciated earlier by the then Archbishop Bergoglio.

The exchange between the Archbishop and the Rabbi covered such core faith-based topics as On God, On the Devil, On Atheists, On the Disciples, On Prayer, and On Guilt. It is interesting how the two leaders agree on fundamentals and yet part ways on specific actions.

The dialogue also dealt with burning issues of the day, like On Fundamentalism, On Money, On Women, On Euthanasia, On Abortion, On Divorce, On Same Sex Marriage, On the Arab-Israeli Conflict and Other Conflicts, On Globalization, On Communism and Capitalism, and On Poverty.

The two leaders then tackle issues close to their hearts like On Religion, On Religious Leaders, On Interreligious Dialogue, and On the Future of Religion.

Are these relevant to executives and hard-nosed businessmen?

You may ask why we are now talking about things of the “faith” or “religion,” when we have sidestepped such topics in the past, confining ourselves to the “secular.”

Something happened along the way. Matters of spirituality are often discussed in board rooms now. People no longer see a dichotomy between the sacred and the secular.

On money, for example, the Archbishop is witty: “There is a saying from a first century preacher that behind a great fortune, there is always a crime.”

And yet he changes gears: “I do not think this is always true… Some believe that, by giving a donation, they have cleaned their conscience.”

Rabbi Skorka triggers that Papal remark with this statement: “It is not true that money has no name. You cannot build spirituality with blood money.”

Both leaders wax eloquent when they discuss politics and power. Archbishop Bergoglio says: “If a person tolerates things without fighting for his rights, hoping for paradise, he is indeed under the effects of opium.” (This is his recurring rebuke to Karl Marx’s statement branding religion “as the opiate of the people.”)

Rabbi Skorka, for his part, referring to Marx and Nietzsche, points out: “I try to believe that these must really be intelligent people to ignore the importance of man’s very real search for God… They are confined to materialistic realities.”

The Rabbi is quick to admit, though that “the Church, along with the other religions of that that time (Industrial Revolution) failed to lift people up.”

On the prospects of interfaith dialogue and cooperation, both leaders are optimistic.

The then Archbishop recalled: “The first time that the Evangelicals invited me to one of their meetings at Luna Park, the stadium was full… That day a Catholic priest and an Evangelical pastor spoke.”

He further remembered the Pastor asking if it was all right that he prayed for the Archbishop, and the Catholic leader knelt down (“a very Catholic gesture,” the Argentine bishop added), “to receive their prayer and the blessing of the seven thousand people that were there.”

For such an act by the Archbishop, an Argentine magazine flashed a headline: “The Archbishop commits the sin of apostasy.”

The Archbishop commented on the media reaction with this: “Even with an agnostic, we can look up together to find transcendence, each one praying according to his tradition.”

And the future Pope followed up with a one-liner: “What’s the problem?”

This book has an abundance of Biblical truths coming across as fresh because the Archbishop has always wanted to go back to basics—true his Jesuit tradition. And because he is concerned with the fundamentals of the faith, he sees more common areas of agreement between and among those in the Christian world.

In this dialogue with the Jewish rabbi, visibly absent in the issues discussed are the all-important topic of Christ the Messiah and salvation. Certainly, the issues would be joined, and the parting of ways would be uncomfortable yet inevitable. The book publishers are not in a hurry. Unity is still far off.

And yet there is a palpable sense that the areas between Catholics and Evangelicals can be expanded with Pope Francis introducing earthshaking reforms and extending the hand of cooperation with other faiths. And leaders of other denominations have similarly expressed openness.

Something urgent is foremost in their minds: Saving people cannot wait, and alleviating suffering is urgent.

dmv.communications@gmail.com