Quite recently, we gathered that Jollibee Food Corporation bought out majority shares of Mang Inasal, a new kid on the block that made a name in serving chicken with unlimited rice.

What we didn’t know was Mang Inasal suddenly had earlier dotted street corners in major thoroughfares, and it was enjoying a stream of customers who craved for much more rice for their comparatively small portion of chicken.

Speculations were that Jollibee’s “chicken joy” faced a serious challenge from Mang Inasal’s chicken, but from the latter’s unlimited rice. (“Unli” has been popularized by Smart and Globe.) Of course, Jollibee was – and still is – a believer in the altered saying, “If you can’t beat ’em, buy ’em”!

The rest is recent business history in M&A (mergers and acquisitions). Earlier, Jollibee also bought Chowking, driven by the same principle.

But, the point of the story is that there have been business upstarts under the general category of small businesses, here and around the globe, that challenged established industry giants – and coming away with a substantial, if not most, of the market share.

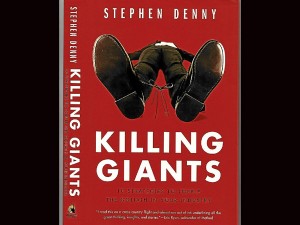

Watch out for Davids in Business. “Killing Giants,” written by Stephen Denny, is a take-off from a favorite story of David felling Goliath in Biblical lore. Armed with only a slingshot and five pebbles, young David faced the fearful giant of a Goliath – and fell him with a single shot at the forehead. (The book’s cover, however, confuses that story with the Lilliputians who tied up a giant while the latter was asleep.) Anyway, the central message was – and is – hat the size of giants can be their own weakness and their reason for defeat.

Ten chapters, ten strategies

Author Denny devoted ten chapters for ten strategies to trounce industry – or brand – leaders thus: Thin Ice, Speed, Winning in the Last Three Feet, Fighting Dirty, Eat the Bug, Inconvenient Truths, Polarize on Purpose, Seize the Microphone, All the Wood Behind the Arrow(s), and Show You Your Teeth. The last chapter, provide a wrap up and “last instructions” from the author.

Run light, not heavy. “Running on Thin Ice” is an easy territory for business upstarts but a scary one for industry giants whose sheer weight will break the ice from under their feet. “Thin ice” is dangerous to companies who are too big to venture far from the relative safety of familiar ground,” the author points out.

He advises scrappy and cash strapped start-ups to create their own “thin ice” where giants fear to tread. He cites a handful of examples, one of which is Boston Beer, which exclusive positioned itself thus: It is not “a beginner’s beer”; rather, it is “the exclusive choice for those people who consider themselves sophisticated beer drinkers. At our Marketing Class at the Asian Institute of Management, we were given the product a “snub appeal.”

Based on two other success stories of scaring off brand leaders, the author dishes out “enduring lessons,” like: “Setting out to change how millions of people think about your product category is fundamentally different than deciding to make a good product.” Our local giants and upstarts can learn from this, no matter whether you are the “challenged” or the “challenger.”

Nurture culture of speed. Another interesting topic is “Speed.” The author also reflects speed and ease in reading in his prose. Read this summary, which tells the reader what he/she expects from the discussion: “Giants have a culture of process. You have a culture of speed.” He is obviously addressing the “challengers.”

It must be added quickly that this book could also be valuable to industry or brand giants, because they will see the strategies and tactics of “new kids in the block” who make it their business to gnaw into their market share, as they draw their existing customers to their “new and exciting product.”

To drive the point of the crucial importance of speed in business success, Denny cites the new training of drivers and pit draws in Formula 1 racing. They must be able to change tires in a very coordinated fashion in 2.5 seconds, an improvement from those doing it in 4.5 seconds. The rule is: “If you can shave half a second off every stop compared to your competitors every time … half a second is a lot of time in this competitive world.”

The book cites about three cases of smaller companies beating industry leaders due to their sheer speed in decision-making since they were not constrained bureaucracy and multi-layered processes in a big organization. The book also cites the dramatic political victory of Scott Brown to win a Senate seat in Massachusetts, wresting an amazing win from a veteran. Scott Brown relied on the speed on social media.

Intercept at the last decisive moment. “Winning in the last three feet” is a smart firm’s strategy to “snatch victory from the jaws of defeat.”

Denny relies on an old retail expression which rightly knows that “it’s never over until it’s over.” This sounds like guerrilla selling, or it reminds us of the intercept of a basketball star Freddie Webb at the hard court when the other team thought the basket was theirs.

This takes off from a homespun truism that says: “Iyung pagkain na isusubo na ay baka mahulog pa.” The author, making every lesson interesting, recalls the fight of boxing champion Joe Louis who was already losing the bout. The opponent, Billy Conn knocked him down – and Conn confidently told his handler that he would go for a knock out. The handler tried to dissuade him from risking it since anyway he was leading in all rounds. But, Conn tried to go for a dramatic knockout – only to be stopped at the 13th and final round by Louis’s short right upper cut.

The business challengers would forever be waiting and working for that moment when the “tide turns” – and the customer makes a switch in their favor. This is also true for persistent suitors. They wouldn’t stop until their “true love” walks down the aisle.

“Fighting dirty” is not really an endorsement of being unethical; the author makes an overkill with words. Denny is more precise when he says: “Make them (giants) fight where they don’t want to fight, and use tactics they find difficult to counter.”

Start-ups work, study harder. The author also advises the smart little businesses to do their homework. You must know everything about your “enemy”: where he buys his raw materials, which banks he uses, and what margins he makes from his products. These will give ideas to the start-up to go for a price war or for a value-for-money tactic.

Check their inventory turns, the author advises. “Your turns will be a function of the amount of inventory your retailer carries – the number of facings they have one the shelf plus inventory – and the speed at which consumers pull them off those shelves and put them in their shopping baskets.” Very graphic description of winning in the marketplace!

“Move your customer from the emotional to the rational” is the author’s advice in changing a mindset in whether you should “own” a car or “use” it. This thought alone has made a success out of Zipcar, a membership company which allows members to use their cars at a very low price, much lower than the monthly, daily equivalent of buying a car. It’s a competitive weapon that would lower sales of brand new cars – or any other products – because this emanates from the tactic asking customers to consider “consumption without ownership.”

Making noise about yourself is the topic of “seize the microphone,” where the start-up can dominate discussion in a product category. “How can they buy your product if they don’t know that your product exists?” Start-ups used this to the hilt to steal market share from the industry leader.

On the whole, “treading on thin ice” and “having a culture of speed” are the two useful tips for the challengers out to wrest a market from old-timers and the big guns.

No more market testing. I got hold of a speech by a former Smart Communications executive who spoke of the same need for speed – this time in introducing a new service. He said that we now live in a fast-paced world, a transparent community. What we do or invent has a way of reaching competitors. Thus, he and his team in Smart got feedback from their employees that they wanted to share their load to those in need of load. So, without the benefit of “market testing,” which should have been the standard process in trying a prototype, the “Pasa Load” product was launched, taking competitors by surprise – and taking the market by storm.

What this tells us is that even industry giants can use speed like small firms do. Thus giants can act like Davids in the marketplace. (Send comments to dmv.communications@gmail.om)